He was half-right. The Graduate, which joins the Criterion collection on Tuesday, isn’t an inspirational tale of young people overthrowing their parents’ materialistic, conformist attitudes in favor of freedom and true love—but then, it never was. The film’s magnificent cringe comedy derives from Benjamin’s utter cluelessness, which he never overcomes, even when he belatedly takes decisive action. Ebert’s description in his 1997 review is entirely accurate—his mistake was believing that his original, “Go Ben go!” reaction was what director Mike Nichols (working from a brilliant screenplay by Buck Henry and Calder Willingham) had intended, and that his more cynical response three decades later works against the movie’s grain. The Graduate has always been distinctly acid-tinged. That’s its particular and enduring genius.

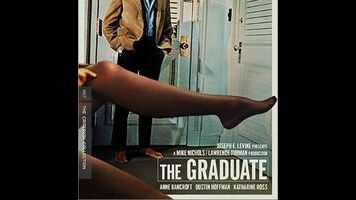

That’s most apparent in Nichols’ revolutionary decision to cast Dustin Hoffman, who speaks at length in one of the Criterion edition’s supplementary interviews about his conviction that he was completely wrong for the part. (Nichols also discusses the subject with Steven Soderbergh on one of the disc’s two audio commentaries.) In Charles Webb’s 1963 source novel, Benjamin is the epitome of the WASP jock; the obvious choice for the role was the young Robert Redford, who reportedly lobbied for it. Instead, Nicholas chose the somewhat nerdy Hoffman, who created a performance that’s somehow robotic and intensely neurotic at the same time. Utterly adrift in the opening scenes, during which he’s assailed on all sides by adults demanding answers about his future, Ben becomes easy prey for Mrs. Robinson (Anne Bancroft), a family friend many years his senior (though Bancroft was in fact only six years older than Hoffman, playing a recent college grad at age 29). Her seduction, which runs over multiple scenes, remains one of Hollywood’s most glorious extended comic duets, with Mrs. Robinson’s sangfroid in hilariously direct proportion to Benjamin’s flustered anxiety.

One aspect of The Graduate that Ebert oddly ignores in his downgrade is its formal innovation, which hasn’t dated in the slightest. Nichols had made only one previous feature, Who’s Afraid Of Virginia Woolf?, a deliberately claustrophobic chamber piece. Here, he shoots widescreen compositions that use the entire width of the frame to striking effect, and alternates between lengthy choreographed shots and jarring cuts (the most memorable being three consecutive shots of Ben turning his head when Mrs. Robinson walks into the room naked, and a surreal match cut from Ben pushing himself off of a pool raft to Ben landing on top of Mrs. Robinson in bed). His use of Simon and Garfunkel’s music was equally revolutionary—movies had employed pop songs before, but never by combining one artist’s back catalogue with original material composed expressly for the film. (The version of “Mrs. Robinson” heard onscreen even syncs up with Ben’s car running out of gas, via a guitar part not found on the single.) None of this feels moldy or antiquated today. If anything, The Graduate’s sensibility feels remarkably modern.

That’s especially true of its ending, which ranks among the greatest and most influential in cinema history. Again, Ebert’s revised take on this is both accurate and misguided. “As Benjamin and Elaine escaped in that bus at the end of The Graduate, I cheered, the first time I saw the movie,” he wrote. “What was I thinking of? What did the scene celebrate?” Well, exactly. By keeping the camera rolling long after Hoffman and Katharine Ross (playing Mrs. Robinson’s daughter, with whom Ben falls in love, inspiring mom’s wrath) expected to hear “Cut!”, Nichols captures exultation gradually fading into uncertainty and doubt, thereby undermining their ostensible victory. They did it! Now what? (At which point “Hello darkness, my old friend” shows up for a reprise.) The cognitive dissonance this produces is entirely by design, and criticizing The Graduate for being a generation-gap wish-fulfillment fantasy that flatters the young amounts to blaming the movie for your own misunderstanding. Ebert was a titan, but in this instance, he was right the first time.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from The A.V. Club.