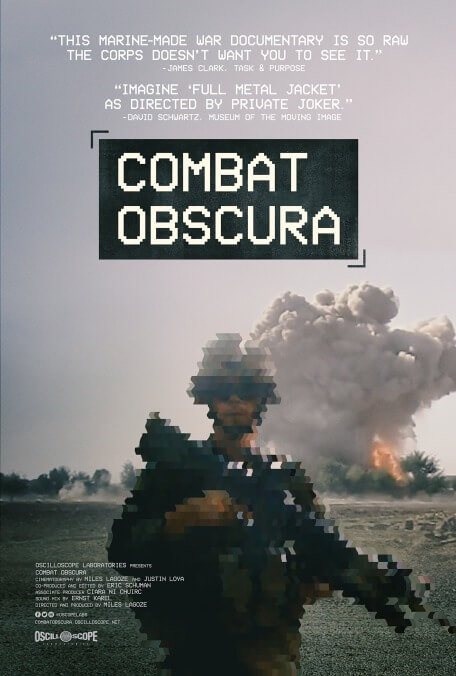

Miles Lagoze, a former combat cameraman for the U.S. Marine Corps, opens his war documentary Combat Obscura with a revealing statement of method: “We filmed what they wanted, but then we kept shooting.” As the official videographer of the 6th Marine Regiment’s 1st Battalion in Afghanistan, he was responsible for capturing footage that “they” (the Marine Corps) could use for recruitment videos and military propaganda, and thus project an authoritative image of justice and and moral rectitude. The roughly hour-long Combat Obscura, assembled from material that Lagoze and other cameramen shot from 2011 to 2012 (and which he revisited years later while enrolled in Columbia’s film program), shows us what’s been left out from years of state-sanctioned publicity. Unsurprisingly, the results aren’t pretty. (On the grounds that the raw footage was captured with government-owned equipment, the USMC threatened, but did not follow through, with legal action against Lagoze.)

Anyone who still thinks of America’s presence in Afghanistan as a heroic affair will be swiftly disabused of that notion. There aren’t any direct verbal denouncements from any of the marines, but the chosen footage makes it clear where Lagoze stands. (In one brief scene, a soldier inspecting a grisly corpse says only: “Oh man. We killed a shopkeeper.”) Eschewing voice-over, basic date and location cards, and really any sort of narrative shape, Combat Obscura consists mainly of disorienting flurries of brusque, brutal action alternated with stretches of uneasy repose.

For a while, this approach is productively amorphous. Even in scenes of relative calm—the soldiers smoking hash, patrolling the desert, or just horsing around—there’s always the sense that all hell could break loose at any moment, a feeling that Lagoze frequently augments by abruptly cutting to deafening firefights. A number of sequences with the local children are especially unsettling, observing as the men offer the kids cigarettes, let them play with their firearms, and tensely question them about possible bombs. Though there’s no attempt to develop any particular personalities among the battalion, we’re given disconcerting glimpses of its members, whom one marine describes as some of the “most fucked up individuals I’ve ever met.” Eventually, though, Lagoze’s relentless horror show becomes rather numbing. A sequence that follows a few men beheading a chicken for sport with others callously inspecting a man gunned down “like a deer” is certainly emblematic of the Corps’ senseless violence (and that of the greater Middle Eastern conflict). But this thudding juxtaposition offers neither novel insight nor incisive observation.

Lagoze, who enlisted in the Corps at 18, has acknowledged an enduring obsession with Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, the poster for which can be seen in the bedroom of a young Spencer Stone in Clint Eastwood’s recent The 15:17 To Paris. Though largely unwatchable, the 2018 film sharply delineated the mechanisms by which scores of American boys are, from birth, practically pre-programmed with notions of militarism, Christian self-sacrifice, and unblinking patriotism. In that respect, Eastwood’s dramatic re-enactment serves as a useful complement to Lagoze’s disjunctive documentary. If The 15:17 To Paris saw three men who managed, against all odds, to fulfill their deeply ingrained ideals and become American heroes (“We got lucky,” one of them says toward the end), then Combat Obscura observes the countless others for whom heroism is no longer in the cards. It may not offer much more than a hellish, on-the-ground vision of the war in Afghanistan, but perhaps it’s enough that Lagoze detonates any lingering illusions of military heroism.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.