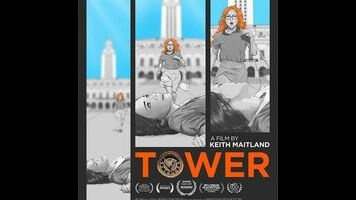

The gripping Tower highlights bravery in the face of horror

Whenever some deranged madman commits murder on a grand scale, we console ourselves by noting that such tragedies, even as they highlight the worst aspects of human nature, also reveal just how courageous and empathetic we can be at our best. That’s the deeply moving essence of Keith Maitland’s quasi-documentary Tower, an abstract, experiential reconstruction of what was arguably the first truly notable mass shooting in American history. (A few previous examples exist, but they don’t appear to have had the same galvanizing impact in the popular imagination.) All but ignoring former Marine Charles Whitman—who ascended to the top of a clock tower on the University Of Texas’ Austin campus and proceeded to shoot 49 people, killing 15 (one of whom was pregnant)—Maitland sticks close to the ground, providing a harrowing moment-to-moment account that foregrounds multiple acts of genuine heroism. The result comes as close to being a feel-good movie about senseless violence as anyone is likely to get.

The horror that unfolded in Austin on August 1, 1966 is now so commonplace that President Obama’s addresses to the nation, following similar shootings, invariably include a weary phrase along the lines of “So, here we are yet again.” Maitland has found an effective means of conveying how surreal the experience was at the time, however. Verbally, Tower consists of retrospective interviews with a number of survivors and police officers, though their words are spoken—and their actions on the day in question portrayed—by much younger actors. Maitland then combines archival footage with newly shot dramatic re-creations, presenting the latter as black-and-white rotoscoped animation (with occasional eruptions of color: Brief flashbacks are Day-Glo, and the background turns blood red every time someone is shot). The combination of rotoscoping and Austin inevitably calls to mind Richard Linklater’s Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly, reinforcing the sense of a slow-motion nightmare. It’s a canny approach—distancing, by design, yet somehow more intimate than a live-action dramatization would likely be.

Maitland’s boldest decision, though, is to withhold virtually any information about Whitman, even though the gunman’s story is fascinating enough to fuel an entire movie of its own, told from his perspective. (Whitman’s murder of both his wife and his mother, which took place the night before the shooting, is never even mentioned.) Nobody on the ground knew who was shooting at them, or why, so neither do we. Instead, Tower focuses on people like Rita Starpattern (Josephine McAdam), who laid down on blisteringly hot concrete, out in the open, and talked to a gravely wounded, obviously pregnant woman, Claire Wilson (Violett Beane), making sure she remained conscious until help arrived. One of the men who eventually risked their lives carrying Wilson to safety tells his story, as does Allen Crum (Chris Doubek), a bookstore employee who ran out to assist a bleeding victim, then accompanied two cops to the observation deck where Whitman was still firing away. Serving as relatable counterpoint is Brenda Bell (Vicky Illk), who talks frankly about her inaction on that day, ultimately concluding, “I was a coward.”

No doubt many of us, faced with the very real possibility of being killed, would wind up similarly frozen, which makes the bravery on display in this film all the more stirring. (There’s incredible real-life footage of Wilson’s rescue, after she’d been lying beside her dead boyfriend in a pool of her own blood for over an hour, still fully exposed to Whitman all the while.) Maitland’s one big miscalculation involves the point at which the film’s interview segments shift from rotoscoped actors to live-action footage of the actual, now elderly interview subjects. Had this juxtaposition occurred in the last few minutes, it would likely have been quite powerful, making the abstract suddenly and unexpectedly concrete; for some reason, Maitland introduces it at roughly the film’s midpoint, which feels arbitrary and ultimately dilutes its potency. A closing montage of recent shootings, from Columbine to Sandy Hook, is also arguably unnecessary, since Tower is fundamentally neither a lament nor a plea for sanity. Those are vital reactions to gun violence, but this movie offers something equally valuable: the perspective of the terrified, who sometimes look past their fear and take actions that remind us why life is worth living in the first place.