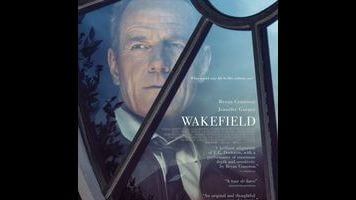

The hammy Bryan Cranston performance is coming from the attic in Wakefield

“Ghosting” is the popular term for when a person simply vanishes from a relationship, leaving no word for the other party. In Robin Swicord’s Wakefield, her protagonist takes “ghosting” to the extreme. One day Howard Wakefield returns to his suburban home during a blackout, chases a raccoon into an attic, and decides to stay there, allowing his resentments to fester until he becomes a hermit, scrounging for food and pooping in a plastic bag. He haunts his wife, examining her life from across the driveway. His actions are a rebellion against the prison of domesticity, until he reaches a place of enlightenment. It’s a tale of what happens when male inadequacy runs rampant, starring a committed Bryan Cranston, but it’s ultimately hamstrung by its overwrought sensibilities.

Swicord adapted her screenplay from a short story by E.L. Doctorow, and she never completely escapes that literary medium. Watching Wakefield feels like listening to an audiobook but with images. Almost as soon as the film begins, Howard’s voice-over is piped in to over-explain the action. His internal monologue, which is relentless, lacks any subtlety, articulating points that are easily inferred. At one point, he muses, “How far am I willing to let this go?” That question is at the heart of the entire endeavor; there is no need to say it out loud. All the while, Aaron Zigman’s heavy-handed score telegraphs ominousness that never manifests into something tangible.

Swicord’s desire to create something of a Hitchcock homage is evident. Peering through glass to invade someone else’s privacy can’t help but recall Rear Window, and overall the movie is infused with a deliberately retro quality. While it clearly is meant to take place in the modern world, its conception of the aggrieved businessman commuter is a relic of the 1960s. Save for luxury cars and household items, there are very few 21st-century signifiers. Yet if you removed all of the plodding obviousness of the piece, it might have something interesting to say about the current state of the American man. Howard is the insidious type that fancies himself an alpha male, neutered by his family. He’s overly possessive of his wife and her body, and yet gets off on the idea of her flirting with other men. He’s a toxic creature initially convinced that he’s one-upping the world by cutting himself off from society. This kind of entitlement—and the subsequent insecurity that results from it—is all too common. What could be a trenchant allegory turns hoary.

It’s hard to evaluate Cranston’s performance under all of the artifice. In the narration, he’s far too mannered, describing his circumstances in florid terms. This is in part the fault of the writing, but Cranston forgoes naturalism entirely in his delivery, and when Howard actually does speak, mimicking the people he’s observing, hamminess takes over. Still, beneath all that, there’s a glimmer of what could have been. Although Cranston’s physical transformation is aided with makeup, he skillfully shifts Howard’s persona just slightly over the course of the film, garnering sympathy while also leaving his ultimate motives obscure. Wakefield is essentially a one-hander, so no one else in the film has much to do, because they exist solely to be reflected through Howard’s gaze. In his mind, his wife Diana oscillates between a feminine ideal and a stuck-up bitch, so Jennifer Garner is largely tasked with playing those two modes. Beverly D’Angelo’s role as the mother-in-law Howard loathes is even more thinly drawn. While Garner tries and infuse the moments she has with depth, D’Angelo is just a caricature.

Howard is a prickly character, but Wakefield isn’t content with being a prickly movie. It’s too quick to spell everything out for its audience, too eager to redeem its unsavory lead. Sure, the ending is just unsettling enough to leave the audience with a queasy feeling, but given what has just transpired, it’s easy to suspect everything will turn out all right.