Patchy but occasionally charming, the Harry Potter spin-off Fantastic Beasts And Where To Find Them delivers most of what has come to be expected from J.K. Rowling’s book series and its successful film adaptations: a hidden world of wizards, prejudices, and bureaucracies, threatened by fascist dark forces from within; sentimental magic that is used to preserve and revive or as a substitute for technology; a surfeit of characters in woolen clothes. The setting is New York City in the 1920s, but though the slang is different (“no-maj,” not “muggle,” is the American magician’s preferred term for those born without wizardry in their blood), the conflict is the same, because the Potterverse only ever fights itself. Hogwarts, the boarding school at the center of the Potter novels, is a place where everyone is special, but is always one administration shake-up away from succumbing to absolute evil.

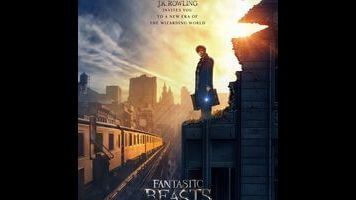

Written by Rowling and directed by Harry Potter film series veteran David Yates, Fantastic Beasts introduces as its nominal hero one Newt Scamander (Eddie Redmayne), an English wizard who arrives on an Atlantic liner with a magical suitcase of zoological curiosities, which in short time is accidentally swapped with a baker’s sample case of pastries. The switcheroo is the one shrewd expositional device in Rowling’s disordered screenplay, because it creates two viewer surrogates for different levels of expertise: Kowalski (Dan Fogler), the mustachioed baker whose dream is to open a Polish-style doughnut shop, swept into magical mischief; and Newt, the Hogwarts graduate adjusting to the different norms of the wizarding community in America.

This lends itself to one of the film’s more inspired sequences, in which Newt and Kowalski are snuck into an all-wizard, women-only boarding house to stay with Goldstein (Katherine Waterston), a hard-nosed investigator of criminal black magic who’s recently been demoted to wand registration, and her flirty sister Queenie (Alison Sudol), a mind reader who has never met a non-magician and regards Kowalski as an exotic creature. But with this and a few other exceptions, Rowling’s quintessentially British fantasy seems to have lost a chunk of its appeal in being moved to the United States. Simply put, there’s no nostalgia to draw on, no comfort to undermine; all Rowling can find in America is the repression and social division that is the dark side of Hogwarts’ aura of belonging, exclusivity, and heritage.

There is no shortage of potential villains in this new world: Mary Lou Barebone (Samantha Morton), the leader of the witch-hunting N.S.P.S., who holds street sermons alongside her clammy Addams Family reject son, Credence (Ezra Miller); Percival Graves (Colin Farrell), the head of the American wizard community’s secret police; the Shaw family, headed by Henry Shaw Sr. (Jon Voight), which wields power and influence in the city’s politics and newspapers; the Obscurus, a malevolent black haze that manifests itself when a child is forced to repress their wizardly gifts. Rowling’s stories, in which everything circles back to the secrets of the past, start from wishful fantasies, and all but beg to be read in broadly social terms.

Fantastic Beasts’ busyness provides the movie with some of its diverting charm: the nonstop movement of the characters between tenement alleys, speakeasies, and Art Deco glitz; into elevators operated by elves and past rows of self-typing typewriters; escapes from dungeons, death chambers, and the unwelcome affections of runaway monsters in heat. But it fails to give these and other threats—most of which amount to little more than preamble for future sequels—a point of attack. Newt, played by Redmayne with a duck-footed walk and an awed whisper, is such a fey character that every other role seems to have been cast as a corrective. And Fantastic Beasts’ New York is barely a place, however expensively realized. As a result, all these monsters and evildoers endanger nothing.

Though Alfonso Cuarón’s Harry Potter And The Prisoner Of Azakaban is popularly considered the best of the Potter film series, Yates’ Germanic Harry Potter And The Deathly Hallows: Part 1 remains the most strikingly stark, an anticlimactic landscape film that consist mostly of haunted spaces and forbiddingly empty country sides. Is there an irony to the fact that Yates, who has become the de facto film interpreter of Rowling’s stories, has shown the most gusto in the movie where he was given the least material to work with? Here, his direction resembles an impersonally fastidious adaptation of a non-existent novel, more focused on hitting plot points to please the fans than on making anything out of them.