The HBO documentary Banksy Does New York asks, “Who owns art?”

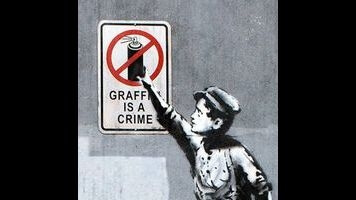

On October 1st of last year, the popular, controversial street artist who calls himself Banksy announced he’d be spending the entire month in the five boroughs of New York City, exhibiting one new installation, graffiti piece, or performance artwork a day. Banksy posted pictures of the finished works, but wouldn’t say where they were located, which meant that Banksy fans had to hunt around the city to find them—all while hoping that the pieces hadn’t been removed or painted over before they could be discovered. Over the course of the month, Banksy stirred up controversy with the political content of some of the work, and provoked the usual brouhaha over whether street art is any different from everyday vandalism. But Banksy also got the citizens of New York talking nearly every day about art and social issues, and he had people paying more attention to their surroundings, looking for hidden Banksys. He kept folks on their toes.

Unlike the excellent Banksy-directed documentary Exit Through The Gift Shop, Chris Moukarbel’s doc Banksy Does New York has no official input from the artist—aside from Banksy’s art, that is, which is all over the film. Moukarbel’s whole premise is that the real art of Banksy’s residency was in the way that New Yorkers interacted with the pieces: by scrambling to take pictures, to shoot video, and sometimes even to usurp them. (Some were stolen, and some were “spot-jocked,” with graffiti artists putting their own tags over Banksy’s.) Banksy Does New York combines talking-head interviews and material from Banksy’s website with local news reports, YouTube videos from passersby, and Twitter posts about the work. The film is about how New York processed and interpreted the Banksy experience more so than it’s about the work itself.

Which isn’t to say that Banksy Does New York doesn’t showcase the art. The film is in the long tradition of “art-docs,” which serve as a kind of video-gallery for people who don’t live in big cities, and don’t get to go see great art in museums. These kinds of documentaries are especially valuable for art that’s here and gone, like performance pieces, Christo installations, or graffiti. A lot of the pieces exhibited during the Banksy residency have been preserved on the Internet (as have the tongue-in-cheek “audio tours” that Banksy provided for the work), but other pieces weren’t static, and aren’t represented well just by Instagram pics. “Experiences”—like when Banksy secretly put an old man out on the street to sell original Banksy canvasses for $60, or when he had a grim reaper spinning around in a bumper car, or sent a truck packed with sad stuffed animals to the meat-packing district—demanded someone with a video camera to convey the moment to those who weren’t there.

And many of the pieces demanded an audience to complete them. A lot of the fun of Banksy Does New York is in seeing how people take pictures of themselves with the work, creating new original art with each snapshot. As Banksy fans point out over and over in the film, often the art generates its own ironies and contradictions, once a crowd gathers. A traveling “peaceful garden,” for example, created such a frenzy wherever it parked that it was all but impossible for any viewer to find actual peace. And whenever the artwork was defaced—and then restored by a group of traveling art-lovers dubbed “the wet-wipe gang”—it raised new questions about what gave Banksy more right than anyone else to claim a piece of the city as his own.

That’s ultimately what makes Banksy Does New York such a lively and engaging film (even if it lacks the endearing puckishness of Exit Through The Gift Shop). Moukarbel ignores a lot of the outcry in New York about the appropriateness—or cleverness—of some of Banksy’s big social statements, like his comments about 9/11 and the Freedom Tower. And Banksy Does New York doesn’t give more than a passing voice to Banky’s critics and skeptics. (If anything, it’s more harsh to the New York art world for largely ignoring the residency.) But the film does a fine job of getting at the tension that each day’s new piece inspired. In the neighborhoods where Banksy struck, some locals fought to preserve the work, some looked to profit from it, and some saw the whole event as a nuisance. Meanwhile, New Yorkers flocked to the new exhibits, and balked whenever anyone tried to restrict their access or mar the art. Intentionally or not, Banksy and Moukarbel raise the question of who these spontaneous acts of creativity belong to, and whether they’re ever really “complete.”