The History Of Science Fiction utterly fails to live up to its title

This reprehensible graphic novel could have been so much more, but instead spends time covering up history, not unpacking it

The setup to The History Of Science Fiction is fairly straightforward: Guides, most of them fictionalized versions of significant white men from science fiction’s past, elaborate on the history of the genre for two robots in a futuristic museum. As comics are the art of sequentiality, a graphic novel purporting to be the sequential history of science fiction—put out by the publisher of so much seminal sci-fi, no less—is likely an intriguing prospect for many comics readers. Presented with an index and a list of principal art sources, the book is clearly attempting to be of some academic or referential use, on top of its wider appeal. But the English translation of Histoire De La Science Fiction fails utterly as a proper historic work—and worse, ends up functioning as weak hagiography.

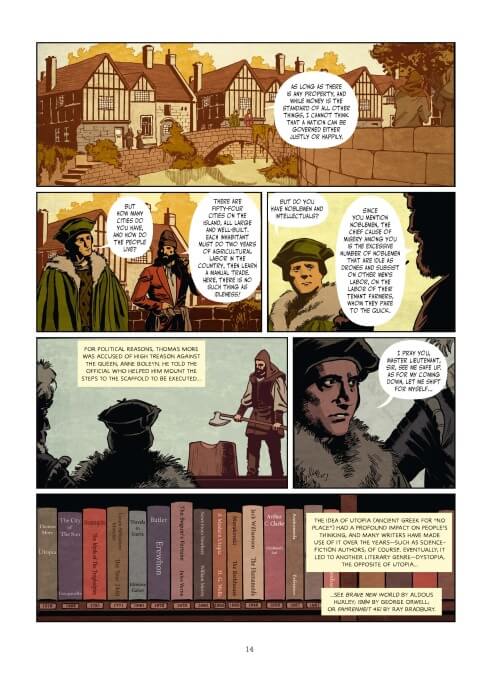

Which is a shame, because the art shines throughout the book. It’s especially wonderful when recreating the angles of famous shots from sci-fi films. In fact, in terms of visuals alone, The History Of Science Fiction would be a commendable work. There is a literal timeline that runs through the bottom of some pages and highlights various sci-fi works, usually relevant to the content on the rest of the page.

Unfortunately, the book also claims to be the history of science fiction; but it only really presents the history of Western science fiction—and a skewed version, at that. More precisely, it primarily functions as a history of science fiction from France, the U.K., and the United States. The notable writers and editors to which the comic team gives literal voice are primarily from those locations, with writers from other countries serving as little more than window dressing. For example, though objects and ideas from Japanese sci-fi litter the futuristic museum, no Japanese author is given anywhere near the depth as writers from the aforementioned countries. Considering that one of the primary sources for this book is able to be precise about its purview (La Science-Fiction En France Dans Les Années 50, or Science Fiction In France In The ’50s), it’s a baffling decision on the part of everyone involved here to not specify this—especially while calling itself history.

Additionally, there is an ugly tendency in the book to gloss over the more reprehensible aspects of the writers featured. At one point, a fictionalized version of British author Michael Moorcock updates a fictionalized H.G. Wells on the state of science fiction after his death. The book has Moorcock say, “Although the Huxley family didn’t always agree on everything, Julian (a renowned biologist who later popularized the term “transhumanism”), Aldous, and you, Herbert, were all staunch supporters of Darwinism and eugenics that would be of benefit to the human race. In contrast to the extremist eugenic ideas of the Nazis, for example.” This statement is nonsensical; even if one accepts the possibility that the creative team wholly disagrees with eugenics but feels that Moorcock—given the opportunity to speak with Wells—would say this, it’s presented without question, when in actuality there is no eugenics “of benefit” to the human race. It literally generates inequality.

There is brief mention of how the closed-mindedness of some lionized writers affected science fiction. For example, John W. Campbell is described as being “marred by racism and rather questionable stances, particularly on pseudo-sciences such as scientology.” However, while the book imagines and renders Campbell’s moments of brilliance in illuminating flashbacks, it does nothing of the sort with his racism, even though those noxious beliefs equally shaped the science fiction of his time and place. Choices like these make The History Of Science Fiction seem absurd as a serious historical work.

Finally, the book comes off as confused about how the history of science fiction has resulted in its present. It quotes Rebecca F. Kuang’s Hugo acceptance speech, outlining what she would tell a new writer of science fiction: “The chances are very high that you will be sexually harassed at conventions, or the target of racist microaggressions, or very often just overt racism.” Yet six pages earlier, it features a hagiography of Harlan Ellison that omits his very public 2006 groping of fellow Hugo winner Connie Willis (there is literally footage of the incident).

By not mentioning this, the book itself contributes to how the larger culture of science fiction—that results in sexual harassment at conventions—is maintained, permitting acts of sexual harassment and assault. The Kuang quote continues, with her saying, “the way people talk about you and your literature will be tied to your identity and your personal trauma instead of the stories you are actually trying to tell.” By including this specific comment by Kuang, who is only mentioned in this instance, and whose work is never discussed, is The History Of Science Fiction not doing exactly what she is decrying?