Don’t let another sun rise on the reaping, Lenore Dove implores Haymitch, but it does, and then it does again, and on and on for 25 more years, until, finally, Katniss breaks the arena, and it works, this time, the last time. Five hundred fifty-one more dead kids and 18 dead adults, in the interim, while the rebels waited for their next shot, knowing they might never get another one, preparing for it anyway because the thought of simply giving up, of accepting the flatly unacceptable, was so much worse than death.

In the original trilogy of Suzanne Collins’ young adult mega-hit book series, The Hunger Games, we get a brief history of its world: A long time before the events of the books, the area once known as North America was devastated by climate change and nuclear war. The country of Panem rose from its ashes, a totalitarian dictatorship controlled from an area called the Capitol, with 13 outlying districts under its control. During the Dark Days, roughly 75-80 years before the start of the first book, the districts rebelled in a civil war against the Capitol, but their uprising ultimately failed, resulting, the Capitol claimed, in the total annihilation of District 13. As punishment for the insurrection, and as an implicit threat to never try it again, the Capitol instituted the Hunger Games, an annual killing competition in which two “tributes” between the ages of 12 and 18 from each district were chosen to fight to the death in an arena until one victor emerged. The process of selecting the tributes was called the reaping.

The first three books in the series—The Hunger Games, Catching Fire, and Mockingjay—were released one per year in 2008, 2009, and 2010. They follow Katniss Everdeen, one of the District 12 tributes in the 74th Hunger Games, as her initial desire to just survive and make it back home blooms into a full-fledged rebellion that, by the time Mockingjay ends, successfully overthrows the government of Panem and institutes a democratic republic in its place. Collins released a prequel, The Ballad Of Songbirds And Snakes, set 64 years before The Hunger Games, in 2020, but it was told from the perspective of Panem’s future dictator; it gave context for how the Hunger Games, as an event, evolved into the massive spectacle that they are by the time Katniss is forced to compete, but it didn’t offer many direct connections to the events of the original trilogy.

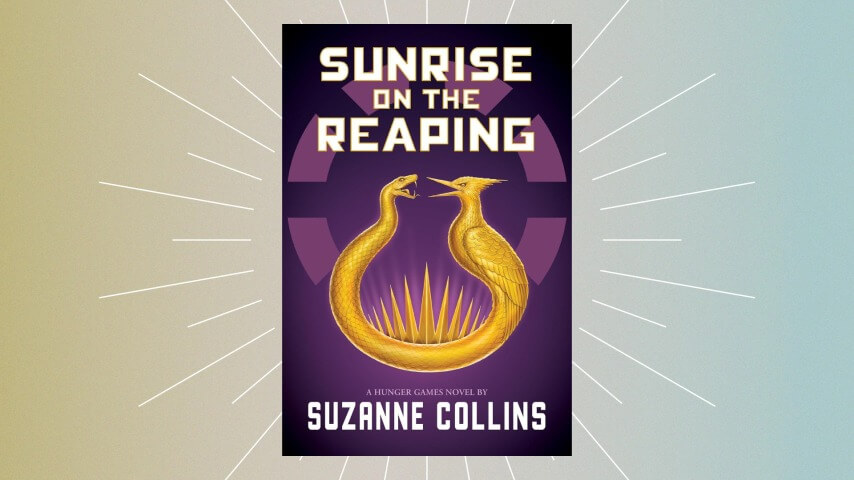

By the time Collins released Sunrise On The Reaping (another prequel, this one set 24 years before the events of The Hunger Games) in 2025, it had been 15 years since readers were immersed in a Hunger Games story told from the perspective of the oppressed rather than the oppressors. In many ways, the world into which Mockingjay was released feels like a lifetime ago: In 2010, I was still in college, still living in a shitty dorm room with a randomly assigned roommate who disappeared for days on end. I was still optimistic about Barack Obama’s presidency, though my rosy-eyed view of that time eventually faded. Now, I’m well into my thirties; I haven’t lived with a roommate for more than a decade. We’re living through Donald Trump’s second presidency, as he tries, every day, to expand the limits of presidential power and bypass key democratic systems in order to exert his will over the American people, as many people are asking, some for the first time, what is required of them when their democracy feels unstable, and what we owe each other as citizens, friends, and neighbors.

Culturally, the world is in a very different place, as well: The Hunger Games is the last bastion of the early-to-mid 2000s dystopian YA boom that saw series like Divergent and The Maze Runner triumph briefly before fizzling out. In 2010, Netflix was still three years away from releasing House Of Cards, its first original series; Spotify didn’t launch in the U.S. until 2011. The weight and distance of the past 15 years are palpable.

The revolution to overthrow the government of Panem, as we understood it before Sunrise On The Reaping, sprung, sudden and nearly fully formed, around Katniss and her act of rebellion in the 74th Hunger Games. She and Peeta Mellark, the other tribute from District 12, were the last two players remaining in the Games, and they planned to die by suicide by eating poisonous berries rather than let the Capitol win by forcing one of them to kill the other. Instead, the Capitol declared them both victors, setting off a rebellion the likes of which hadn’t been seen in Panem since the Dark Days. Sunrise On The Reaping radically alters our understanding of Katniss’ rebellion. This wasn’t the first time since the Dark Days that someone tried to bring an end to the Hunger Games and free the districts from the Capitol’s control; it’s just the first time it worked.

The only hint we get in the first three books that something akin to the unrest caused by Katniss’ stunt with the berries has happened before is a mysterious line from her mom in Catching Fire after the Peacekeepers, the Capitol’s military, begin cracking down on District 12: “So it’s starting again?” she asks Haymitch Abernathy, the only other living Hunger Games victor from District 12 aside from Katniss and Peeta. “Like before?” “I don’t know exactly what my mother means by things starting again, but I’m too angry and hurting to ask,” Katniss narrates. She never does end up asking.

Haymitch, a middle-aged, alcoholic bully in the original trilogy who serves as Katniss and Peeta’s mentor for the Games, is the protagonist of Sunrise On The Reaping. He’s 16 years old in Sunrise, one of the four tributes from District 12 at the 50th Hunger Games (since it’s a Quarter Quell, a special edition that occurs every 25 years, there are twice as many tributes from each district that year). Like Katniss, he’s initially only concerned with making it back home, but slowly awakens to revolutionary consciousness as the injustices he experiences begin to build.

During his time in the Capitol before the Games start, he encounters several characters who also appeared in the original trilogy. Mags Flanagan, from District 4, the victor of the 11th Hunger Games, and Wiress, from District 3, the victor of the 49th Hunger Games, are the mentors for Haymitch and the other District 12 tributes, since there are no living winners from their district. Beetee Latier, also from District 3, the victor of the 34th Hunger Games, is one of the mentors for his district and a trainer for all of the 50th Hunger Games tributes. Plutarch Heavensbee is the camera operator assigned to District 12, tasked with capturing footage of the tributes before they enter the arena and crafting a narrative through spin and propaganda. Mags, Beetee, and Wiress were all tributes in the 75th Hunger Games (another Quarter Quell, in which the tributes were chosen from each district’s victors that time) that take place in Catching Fire, while Plutarch, by that time, was the Head Gamemaker of the Hunger Games. Together, Haymitch, Beetee, and Beetee’s son, Ampert (one of the tributes from District 4), come up with a plan to break the arena and stop the Hunger Games, while Plutarch, Wiress, and Mags provide support.

Haymitch gets pretty close to pulling it off, too. During the Games, he and Ampert flood the arena, but it’s not enough to cause the whole system to malfunction. They don’t stop the Games; the citizens of Panem never even know they did anything at all. In the end, all he’s able to do is make the Capitol look foolish: After he finds the edge of the arena, he realizes there’s a force field around it. Anything he throws into it will come right back out. And when he throws an axe into that force field and it bounces back to kill the last remaining tribute besides him, leaving him as the winner, the Capitol has no choice but to show it on TV.

It’s a small victory, but it’s not enough. He wanted to end the Hunger Games, but he failed, and it cost him everything. In retaliation for his act of rebellion, President Snow, the leader of Panem, has Haymitch’s mom, brother, and girlfriend, Lenore Dove, killed. In the aftermath, Haymitch asks Plutarch what the point of it all was. “You were capable of imagining a different future,” Plutarch responds. “And maybe it won’t be realized today, maybe not in our lifetime. Maybe it will take generations. We’re all part of a continuum. Does that make it pointless?”

It takes another 24 years of underground organizing before Katniss unknowingly lights the spark of a rebellion whose smoldering embers had been carefully tended and kept alive all that time. Sunrise On The Reaping reveals that the rebellion certainly accelerated because of her actions, but it didn’t form because of her; it had been there all along. That realization is even more staggering because, in the real world, so much has changed in the past 15 years that it feels like forever since the original Hunger Games trilogy ended. Now imagine adding nine more years to that. Because there was such a significant gap in time between Mockingjay and Sunrise On The Reaping, it’s easier to picture just how excruciatingly long it must have felt for people like Beetee, who kept working against the Capitol long after they reaped his son as punishment for sabotaging their communications system, long after Ampert died fighting them, long after there was any realistic hope that he might get another chance to bring the Capitol down for good. This was never just Katniss’ fight.