The octogenarian screen legend plays Harriet Lauler, the tut-tuting menace of the fictional town of Bristol, California—a retired ad executive known for requesting refunds for pelvic exams and balking at the quality of Communion wine. Sick of reading rosy obituaries for hated neighbors, she decides to order one of her own, barging right into offices of the struggling Bristol Gazette. Of course, the Gazette’s obit specialist, Anne Sherman (Amanda Seyfried), can’t find a single person in town with anything nice to say about Harriet, but her boss needs her to humor the old lady anyway; he’s banking on the possibility that Harriet might leave the newspaper a chunk of her sizable fortune when she kicks the bucket for real.

Humoring Harriet means helping her fulfill what she believes to be the musts of a perfect obituary: develop a quirky sideline (morning drive-time DJ at a tiny radio station), make amends with her long-estranged daughter, find a former employee who likes her, and “procure a disadvantaged minority child.” It would be mean to pin a movie’s problems on a little kid, but the character of Brenda (AnnJewel Lee) speaks to everything that is lazy, cynical, and cloying about The Last Word. She’s the foul-mouthed 9-year-old that Harriet picks as her mentee after hearing her cuss out the Dewey Decimal System at a local community center.

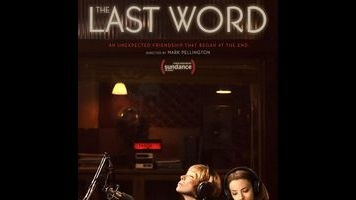

To put it as politely as possible, Lee is a very promising young actor, and her role in the film is that of a tokenistic contrivance: She exists only to show that the micro-managing, wine-swirling curmudgeon—think Lucille Bluth with a riding mower—has a warm heart after all. Pellington, a music video veteran who was once known for inconsistent-but-diverting thrillers like The Mothman Prophecies and Arlington Road, doesn’t show much interest in making either of movie’s central relationships work, leaning on the brittle, snappy MacLaine to carry almost every scene. (Seyfreid is an actor who deserves well-developed roles; this is not one of them.)

Aside from a handful of funny early scenes that focus entirely on Harriet, the only things that seems to make Pellington perk up are the retro trimmings: the sagging, fluorescent-lit basement of the Gazette; the sticker-and-poster-covered interior of the radio station; Anne’s grungy bohemian apartment. In a somewhat inspired sequence, Harriet—who has argued her way into a radio hosting gig with the iron-clad logic that she is so old and rich enough to never be late and work for free—watches Anne meet-cute with the evening DJ (Robin Sands) on whom she’s long had a crush. The whole thing is framed from Harriet’s point-of-view, through the sound-proof window of the broadcasting booth. Like MacLaine’s performance, it begs to put in a movie with more ambition.

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)