The internet’s most infamous frog gets a documentary redemption in Feels Good Man

The ways in which the internet has changed (and possibly ruined) humanity are seismic and yet to be fully understood. But there’s one peculiarity of the online ecosystem that becomes painfully obvious the moment one dares to, say, make an irreverent joke about Spider-Man on a pop culture blog: When someone acts like an asshole online, you’re supposed to just sit there and take it. If someone came up to you at a supermarket and said, “You’re a disgusting pig and I hope you kill yourself,” you’d be justified in at least replying, “Hey, fuck you, buddy!” But online, the conventional wisdom is to pretend like none of it is happening, lest you make the attacks worse by defending yourself. Because if you defend yourself, you’re admitting that these hurtful words got to you. And on the internet, where lulz are king and caring is for cucks, any sign of sincerity or emotion—let alone vulnerability—can be fatal.

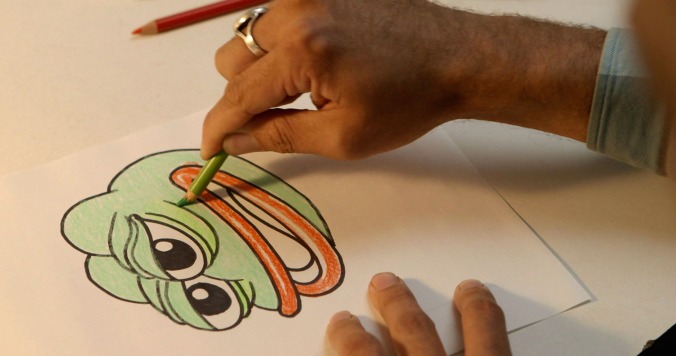

No one knows the corroding effects of this malignancy better than Matt Furie, the Bay Area cartoonist who created Pepe The Frog. Originally conceived as the permanently stoned “little brother” character of a sitcom-esque crew of cartoon party dudes in Furie’s late-’00s comic Boys Club, Pepe went from a single six-panel comic uploaded to Myspace to being officially declared a hate symbol in less than a decade. This journey is chronicled in the new documentary Feels Good Man, which begins with Furie creating Pepe and ends with him trying to reclaim the character from white supremacists and “alt-right” shitposters.

How this happened is the stuff of book-length analyses, and Feels Good Man sprints through the history of memes and the evolution of online nihilism from its relatively innocent origins—alienated adolescent males commiserating with each other on message boards like 4chan—to its co-option by Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. But this is a case study, not a survey. And the character of Pepe is intrinsic enough to this progression that simply documenting Pepe’s devolution over the years serves as a shorthand for the larger story. As Furie succinctly puts it, “It’s just, like, fucking garbage world.”

Along the way, director Arthur Jones manages to dig up interview subjects whose soundbites would be funny if they weren’t so real: Take the proud owner of a “rare” Pepe meme purchased for nearly $40,000 at auction, or the 4channer who explains that Pepe culture took a dark turn when “sex haver[s] and wom[en]” discovered the frog. Ridiculous, right? But that’s the point—as Feels Good Man illuminates, the adoption of absurd jokes like Pepe as mascots for racism, anti-Semitism, and misogyny girds that hate in the armor of irony, a process that eventually breaks down the concept of reality itself. Think Alex Jones—a loud, enraging presence in Jones’ doc—calling himself a “performance artist” or Trump’s own insistence that his statements are jokes whenever he receives backlash.

Feels Good Man would be a valuable addition to our current cultural moment if it were simply an intelligently assembled explainer on irony poisoning. But Jones and producer Giorgio Angelini—who shares an “a film by” credit with the director—have also created a character study of Furie, who comes across as a sweet man who likes drawing, cats, and hanging out with his daughter and whose only crime was not being able to predict the future. That characterization also applies to his inner circle of artist friends; in one particularly pitiable scene, Furie’s roommate shows the filmmakers the Pepe tattoo he got during the heady first days of the character’s popularity. These poor bastards learned from experience that once a character goes out into the world, you can’t control it anymore—not even if the creator kills it off, as Furie did with Pepe in 2017.

Furie isn’t completely without agency, however, as shown in the film’s oddly hopeful final stretch. Just making this documentary is a step toward the redemption of Pepe, ending on a note of animated optimism as Pepe ascends into a nirvana of good vibes and peaceful intentions. (As one might hope from a documentary about a cartoonist, the animated sequences in Feels Good Man are far above average.) Simply reclaiming this one character won’t fix everything—as is stated more than once in the documentary, the genie cannot be put back into the bottle. Things are likely to get (even) worse before they get better, but if you want to fight something, first you have to understand it. Feels Good Man does just that, and it’s pretty darn entertaining, too.