The invaluable Invisible Planets introduces the world of Chinese sci-fi

“Some said that outside the borders of the State there were other web sites, but those were only urban legends.”

—Ma Boyong, “The City Of Silence”

“The machines pretty much ran on their own, and there were very few workers. At night, when the workers got together, they felt like the last survivors of some dwindling tribe in the desolate wilderness.”

—Hao Jingfiang, “Folding Beijing”

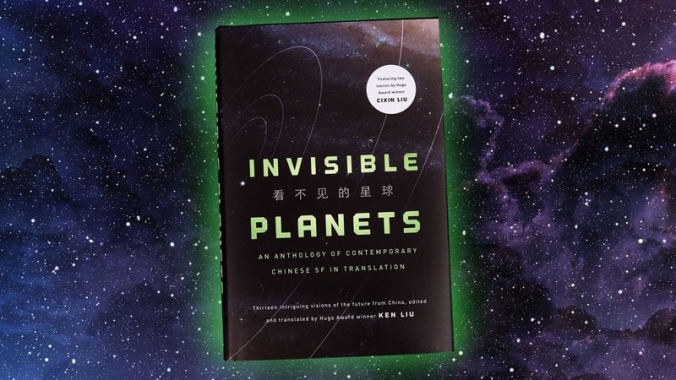

In his introduction to the new anthology Invisible Planets: Contemporary Chinese Science Fiction In Translation, the sci-fi writer and translator Ken Liu warns the reader against drawing generalizations from the stories selected for the book. To put that in perspective: Invisible Planets isn’t just the first book of its kind since Wu Dingbo and Patrick Murphy’s Science Fiction From China (1989), but the handiest primer on modern Chinese sci-fi published to date. In addition to short stories by seven contemporary writers, Liu—whose translation of Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem won the Hugo Award For Best Novel, and who is himself the winner of Hugo and Nebula awards for his short fiction—includes biographical sketches and an appendix of essays in which three of the authors offer their own definitions of speculative fiction and its place in China. But like any good curator, Liu is careful not to over-interpret.

This is the anthologist’s dilemma, which often comes down to a tough choice between accessibility and accurate representation, exacerbated by the fact that the sci-fi short story is a suggestive form that begs interpretation. In Chen Qiufan’s “The Year Of The Rat,” which opens the collection, jobless college grads are sent off to the countryside in squads to fight a continually evolving population of bipedal, genetically engineered rats. Xia Jia’s Ray Bradbury-esque “Tongtong’s Summer” uses the point-of-view of a little girl whose grandpa has been given a remotely controlled robot caregiver to examine how seemingly impersonal new technologies become part of our emotional lives. Hao Jingfiang’s title story, a compendium of imaginary worlds, tells of a planet in hourglass-shaped orbit around two differently sized stars, resulting in long hot and cold seasons ruled by different species who never meet, but worship each other as gods.

“Folding Beijing,” also by Hao, describes a multi-level city where social classes live by different clocks, a la Metropolis. (The story, originally published as a novelette, won the Hugo in that category earlier this year.) The most prescient story in Invisible Planets, Ma Boyong’s “The City Of Silence,” first published in 2005, imagines a totalitarian state that has restricted all information and communication to a strictly regulated internet. Ma writes of computers welded shut, with no hard drives or slots for “CDs or even a USB port”; of data that can only be stored or accessed remotely; of verifications that make it impossible to use the internet under anything except one’s real name. Ironically, what this pastiche of grayish Orwell-isms resembles is not dictatorship or state censorship, but our current capitalist dystopia of Apple products, cloud storage, and Facebook login prompts.

Liu’s smooth translations cover an assortment of styles, from Cheng Jingbo’s opaquely coded “Grave Of The Fireflies” to the Arthur C. Clarke-ian, idea-centric stories of Liu Cixin. (One wonders, though, if “miasma,” used in multiple stories, is a term more common in written Chinese than in English, or a pet word of the translator.) At the same time, Invisible Planets doesn’t attempt to be encyclopedic. Readers already interested in the large body of science fiction produced in China since the 1980s will notice at least one obvious omission in Han Song, an important figure whose short fiction has also been translated by Liu. The three author essays included at the end of the book provide some context. They tell roughly the same story of Chinese sci-fi as a national genre that started early (two reference the fact that Lu Xun, the father of modern Chinese literature, also introduced Chinese readers to Jules Verne), but matured late.

In his essay, which includes a lengthy discussion of Han Song’s still-untranslated novels, Chen calls science fiction “the byproduct of the process of gradual disenchantment with science.” Xia, in hers, dubs it “a literature always in the state of becoming,” citing a favorite term of the French philosopher and critic Gilles Deleuze, and offers up the hope that Western readers of Chinese sci-fi will find “an alternative Chinese modernity and be inspired to imagine an alternative future.” Liu, in his own introduction, flips the popular definition of sci-fi as “the literature of ideas” by declaring, “Science fiction is the literature of dreams, and texts concerning dreams always say something about the dreamer, the dream interpreter, and the audience.”

The task that Invisible Planets has taken upon itself is to introduce to the average English-speaking sci-fi fan something that has mostly been a subject of academic study, all the while respecting the spheres of academia (the stuff of “text” and “modernity”) and genre readership. The challenge is summed up by the way the book handles Liu Cixin’s name: on the cover, it uses the Westernized “Cixin Liu,” in keeping with the English translations of his novels published by Tor Books, but inside, it uses to the proper order, after a footnote on Chinese names. It tackles its problem with intelligence, and in its diverse and often inspired selections, it makes the implicit point that the rapid growth of Chinese sci-fi in recent decades have made it both difficult to define and a microcosm of the various things that speculative fiction can be.

Purchasing Invisible Planets via Amazon helps support The A.V. Club.