Given the overwhelming successes of Illumination’s The Super Mario Bros. Movie and Pixar’s Inside Out 2, feature animation is currently enjoying a renewed position as a dominating box office darling. Not to rain on the parade, especially since any boon for movie theaters should be considered a Good Thing, but those wins aren’t necessarily testaments to the medium. Rather, they merely represent moviegoers’ enduring loyalty to powerful brands. Mario Bros. is Nintendo’s crown jewel, and their unholy union with the Minions-makers practically guaranteed a hit. Meanwhile, Inside Out 2—a serviceable feelings-first cartoon excursion into adolescent ennui—is a safe retreat into franchising by an animation body weathering criticisms that their best days are behind them. Why were these movies such tremendous smashes? Blame brand devotion (and don’t rule out air conditioning).

The American animation landscape is as energetic as it’s ever been, a popular venue to show off the latest top-of-the-line advances in computer techniques. But this thundering success underscores creative limitations in the industry, as it often trades maturity, insightful storytelling, and personal artistry for something much easier to market: Troll-tushin’, Jack Black blusterin’, banana-munchin’ safe bets. When we look at the top-grossing American animation from the last quarter century, it begs a host of nagging questions: Where are the boundary-pushers, the innovators, the audacious risk-takers? Why must family entertainment be ladled out like so much gruel? Lorenzo di Bonaventura, former production president of Warner Bros., once callously but tellingly put it like this: “People always say to me, ‘Why don’t you make smarter family movies?’ The lesson is, every time you do, you get slaughtered.”

That quote exposes the inherent lack of imagination or daring in corporate filmmaking, and explains the mundane state of contemporary animation. Of course, there are exceptions among these studio offerings, films that could have taken the easier route with recognizable IP but pushed the medium to new and thrilling places nonetheless. Sony’s Oscar-winning Spider-Man: Into The Spider-Verse is notable for taking decades of superhero comic iconography and enhancing it with dazzling fidelity. The team behind it instilled their vibrant candy-colored magic with humanity, drama, and interpersonal strife. The superhero movie, a genre that currently suffers its own host of woes, got a well-considered and much-needed kick in the pants by Miles Morales, and pop animation has been all the richer for it.

Yet even Spider-Verse’s success can’t compare to Illumination and Pixar’s billion-dollar hauls, which prompts another troubling question: Why do thoughtfully crafted animated features inspired by personal experience and a clear artistic voice seem like rare, experimental outliers rather than the standard by which all family entertainment is measured? Di Bonaventura might have been on to something, damn him, but must it always be this way? Those who remember know there once came a pivotal moment for the medium with the release of Brad Bird’s The Iron Giant in 1999, a film that, had it achieved any commercial success (any, at all), might have dramatically shifted the trajectory of animated filmmaking.

It’s comforting to consider an alternate reality where The Iron Giant, a delicately told story and masterfully executed blend of CG and hand-drawn animation, was a box office hit instead of a colossal flop. It arrived at a time when fierce competition in dazzling 3D computer animation was ramping up, with Pixar/Disney and DreamWorks actively hustling for the CG insect dollar with their 1998 releases (A Bug’s Life and Antz, respectively). Prior to acquiring Pixar, Disney’s success in the late ’80s and early ’90s stemmed from a winning, but obvious, formula: pluck a fairy tale or myth from the public domain, imbue it with a host of marquee acting talent, toss in a sassy sidekick of various makes (be they candelabra, monkey, or warthog), don’t forget those soaring musical numbers, top it off with a squishy ending, and boom—a hit.

This Disney Renaissance produced instant classics like Beauty And The Beast, Aladdin, and The Lion King. Warner Bros., eager to cash in on the bonanza after setting the commercial/artistic bar quite low with Cats Don’t Dance, ventured into the animation arena with Quest For Camelot, a treacly and uninspired echo of their competitor’s rousing musicals. By attempting to replicate that Disney magic, they released a commercial and critical dud. Reviewing for the L.A. Times in 1998, David Kronke rightly articulated Warners’ transparent foray into Disney territory by writing, “[Camelot was] clearly concocted to recall and distill elements of recent animated successes—so much so, alas, that it lacks a distinct personality of its own.”

Warner Bros, once famous for their subversive Looney Tunes (which had received a wild boost following 1996’s live-action/animation hybrid Space Jam), suddenly looked stodgy. Quest For Camelot’s failure contributed to the dwindling prospects of Warner Bros’ fledgling feature animation division, an unhappy environment where ex-Disney animator Brad Bird, fresh off a celebrated run on The Simpsons, pitched his take on poet Ted Hughes’ fantastical novel The Iron Man. Warner Bros wanted to make it a musical with stars like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Brad Pitt. Bird had other ideas.

“What if a gun had a soul?” was his pitch, an inspired and deeply personal take that broke from WB’s initial plans to turn The Iron Man into a Pete Townsend-penned musical romp. “How is that not great for animation?!” Bird recalled asking in “The Giant’s Dream,” a making-of documentary supplementing The Iron Giant Blu-ray release in 2016. “Let Disney do the fairy princesses; that’s fine, but why can’t we do [something different]?”

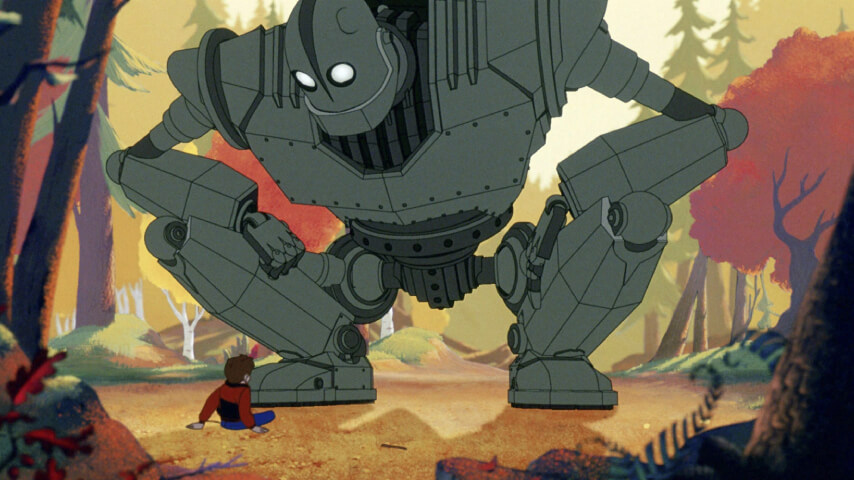

What Bird set out to accomplish felt as distant to its competition (Tarzan was released the same year) as it does the animated movies we see today. Set in 1957, during the height of Cold War anxieties, The Iron Giant elegantly recounts the story of Hogarth (Eli Marienthal), a boy who befriends a metal robot (Vin Diesel). This giant of unknown intergalactic origin and the belligerent hostility it faces from the U.S. government is a suitable allegory for the fear and paranoia of the era, eerily juxtaposed against the looming threat of nuclear annihilation.

The emotional core of Bird’s parable (co-written by Tim McCanlies) is Hogarth’s gentle influence on the Giant, imbued by personal tragedy, both fictional and real (Hogarth may have lost his father during wartime, an echo of Bird’s tragic loss of his sister to gun violence in 1989), guiding its audience to a higher appreciation of compassion and sacrifice. The Iron Giant is informed as much by Rockwellian decency as it is by the sci-fi monster movies of the era.

What inspires multiple viewings of the movie is the framing of its themes. Doom arrives from above twice in The Iron Giant, though ironically, neither instance comes from foreign adversaries—they’re from the stars or, as The Bard would surely appreciate, ourselves. The first time it comes, it’s in the form of this metal space colossus sent to Earth for presumably hostile reasons (as we later discover, it’s quite capable of mass destruction). The second is The Bomb, deployed by the United States government on the screeching orders of a xenophobic government agent named Mansley (Christopher McDonald), who is only interested in ending the existence of this Giant, not in its renewed purpose. So Mansley attacks the Giant, and it defends itself, the potential outcome being mutually assured destruction in the name of thwarting the Other.

At the nexus of this conflict is Hogarth, an imaginative, adventurous kid who, as fate would have it, intercepts this Iron Giant before it does conspicuous damage to his portside Maine home and brings the full force of an anxious government down on their heads. As Scott Tobias wrote in his New Cult Canon feature on the film, boy-meets-alien stories typically show the alien inspiring some sort of change in the boy’s life, and Bird’s film flips that narrative: Hogarth is the catalyst for the Giant’s evolution. His (not “its!”) yen to explore our Earthling ways is encouraged despite the mess he often leaves behind; later, Hogarth gently guides him through complex abstractions like the soul. By the movie’s end, the Giant rescues Hogarth and his hometown by thwarting Mansley and The Bomb, a decision that stems from everything the boy imparts to him throughout their short time together.

It’s no wonder The Iron Giant still hits as hard as it originally did 25 years ago. Like Hogarth, it knows where its heart lies and has something to say about a world fractured by mistrust. Its message is so clear-eyed that it’s easily recontextualized to meet our currently fractured American moment; after all, mistrust of the Other certainly hasn’t diminished since The Iron Giant premiered all those years ago. The movie, sprung from the mind of a socially conscious and literate filmmaker, still offers counter-programming in a studio landscape that more often requires wacky sidekicks, earworm tunes, and/or a landfill’s worth of tie-in merch to greenlight its projects. The Iron Giant offered the promise of something new, a vision more akin to the wondrous projects coming out of Japan’s Studio Ghibli than the standard fare we were getting in the States, something more in touch with who we are. And next to nobody went to see it.

So, what’s to blame for The Iron Giant’s commercial failure? Were its themes too subtle or dark for an industry more enamored with broad, easily digestible spectacles? As detailed in “The Giant’s Dream,” Warner Bros’ reticence to make more animated features following Quest For Camelot’s financial walloping might have given Bird and his ragtag crew of animators more freedom (plus or minus a few loaded exchanges with his producers), but it also put distance between WB and their obligation to market the movie. By the time Bird and his team were putting the final touches on the film, the studio had hardly begun its advertising campaign, despite effusive test screenings strongly suggesting the movie would be a hit with audiences. Millions of people saw Tarzan swinging in from a year away; for The Iron Giant, there were a scant four months of promotion before it was released wide on August 6, 1999.

At least it was an enormous hit with critics— though that hardly moved the needle for moviegoers. Following the disastrous rollout of The Iron Giant, Bird would return to Disney in a roundabout way, as his box office-dominating Pixar films The Incredibles and Ratatouille came as the studio’s relationship with the House of Mouse was changing into acquisition. But as the years progressed, Bird’s impact at Pixar diminished with its insistence on sequels. This decision, made by a company that makes too much money to suffer quieter, less showy releases (as seen with Domee Shi’s Turning Red, whose COVID-affected losses seem to have inadvertently aided Pixar’s strict, anti-creative focus on known properties), conflicted with Bird’s skillset, as seen in the artistically diminishing returns of The Incredibles 2.

It’s also important to note that animation is often conflated with kid-friendly entertainment, which itself is a burden animators have to shoulder when pitching fresh, mature projects to wary studios. The idea that a computer-rendered (or, perish forbid, hand-drawn) feature could cater to all audiences without deploying a battery of fart jokes, bright colors, and a jukebox soundtrack seems like a no-brainer, and yet there are too few examples that don’t insult its audience’s intelligence in the name of turning a buck. And because there aren’t more thematically challenging, personally-crafted animated family entertainments, fewer studio-made animated features are aimed at adults. Heavy Metal, Anomalisa, Waking Life, A Scanner Darkly, Isle Of Dogs, Mad God—these movies, despite their qualities and enduring cult popularity, are outliers in the studio system instead of the standard.

Yet there’s reason to be hopeful for change. The Iron Giant is still making an impression on audiences and the industry, inspiring up-and-coming animators to tell new, thoughtful stories, as has been the case for Elaine Bogan, who worked on Spirit Untamed for DreamWorks. Speaking to A.Frame in 2021, Bogan said of Giant, “Not only was I overjoyed to watch a classically animated movie executed so beautifully, but from a storyteller’s perspective, I remember this movie stunning me with how much emotion was evoked by a robotic character made of metal who spoke very little words.” Even if it didn’t change the trajectory of American animation, the influence of The Iron Giant—an earnest tribute to youthful whimsy, a maverick monster movie that makes our hearts beat in time with its clockwork soul—stands tall a quarter-century later.