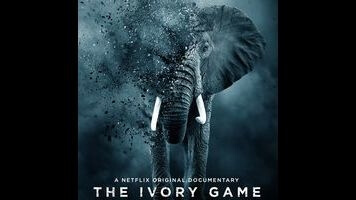

Unlike a lot of other advocacy docs—films that seek to raise awareness regarding some serious issue, often concluding with a call to action—Netflix’s The Ivory Game offers something spectacularly visual: elephants. Those trunks! Those ears! Those… tusks. A book or lengthy magazine article could perhaps better convey the same basic information, alerting people that African elephants are being illegally slaughtered for their ivory at a pace that will result in their extinction within the next two decades. (An elephant is poached every 15 minutes, on average.) Seeing the majesty of these endangered creatures in action, however, juxtaposed with the horrific sight of their mutilated carcasses, inspires visceral feelings of sorrow and anger that no amount of elegant prose can possibly match. That’s why it’s so frustrating that directors Richard Ladkani and Kief Davidson apparently felt that they needed to craft a thriller—complete with pulse-pounding music and a mysterious, all-powerful nemesis—in order to hold viewers’ attention.

The Ivory Game begins strongly, profiling various people who are fighting to protect elephants by different means. A park ranger talks to local farmers, who are upset about the animals eating their crops (and are thus not inclined to report poachers), about plans to build an electrified fence. A Chinese activist, ashamed at his country’s role in the crisis—the vast majority of poached ivory winds up in China, which maintains a legal trade that’s heavily restricted but easily gamed—poses as a potential buyer in an effort to gain information about smugglers. We see officials in Kenya burn their entire 105-ton stockpile of ivory, though the film does a poor job of explaining why doing so will theoretically help stop the killing. (Scarcity drives up prices, meaning that dealers actually want elephants to go extinct, so doesn’t destroying ivory just intensify the problem? No doubt there’s a sensible answer to this question, but it’s not in the movie.) All of these folks seem like heroes, and footage of the elephants themselves—huge and lumbering, yet surpassingly gentle—makes it hard to understand how poachers pull the trigger, even for a huge profit.

Nor does The Ivory Game particularly want to understand, sadly. Even if Ladkani and Davidson were unable to talk to anyone on the other side (which is quite likely), their strenuous efforts to make The Ivory Game exciting as well as informative trivializes the crisis, turning poachers, smugglers, and dealers into generic Hollywood bad guys. Much is made of a shadowy, never-even-photographed figure known as Shetani (“Devil”), the kingpin of a poaching syndicate; after nearly two hours of being discussed in hushed tones, Shetani is finally arrested, but the investigative work leading to this triumph mostly occurs off screen. We never learn anything much about the man or his operation—he just gets endlessly talked about like he’s Keyser Söze, and then suddenly he’s in handcuffs. There’s also an embarrassingly limp sequence involving a hidden camera, which gets discovered mid-sting by Chinese criminals; the movie relentlessly hypes the potential danger, then reveals that everyone involved just walked away with no hassle at all. Granted, advocacy docs tend to be kind of dull, but this one tries way too hard to counteract that perception. When you’ve got beautiful animals at risk of extinction, there’s no need to manufacture tension.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.