The Last Action Hero game accidentally proves the movie’s muddled message

Last Action Hero, Game Boy (1993)

“Magic ticket my ass, McBain.”

—Chief Wiggum, The Simpsons, “The Boy Who Knew Too Much”

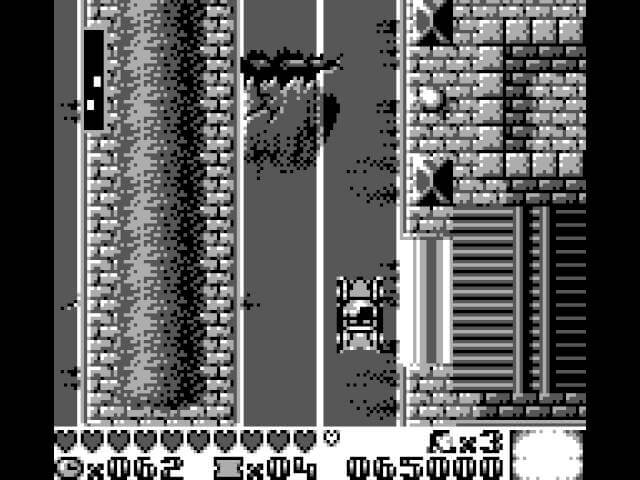

A heavily pixelated Jack Slater runs through a crumbling… factory? Warehouse? Movie theater? He dodges bullets and falling objects. He douses columns of flame. He runs up stairs and jumps over holes in the floor. He uses his powers of… crouching? Kicking? Punching? Fire-extinguishing? He has no gun, no cigar, no wry quips.

In other words: He’s no Jack Slater.

In 1993, Columbia Pictures released Last Action Hero, a meta-blockbuster, brought to life by Predator and Die Hard director John McTiernan, superstar Arnold Schwarzenegger, and a team of screenwriters that included Zak Penn and Shane Black. The movie was predicated on a simple, seemingly bankable idea: that a savvy bunch of filmmakers could give an audience all the over-the-top violence of a modern action picture while simultaneously mocking the clichés. Last Action Hero seemed like a can’t-miss.

It did miss—not catastrophically but badly enough that long articles and book chapters have been written about Last Action Hero’s creative failures and botched marketing. Bad reputation and Razzie nominations aside, though, Last Action Hero isn’t a terrible movie. It’s frequently very funny and thrilling, imagining what would happen if a Schwarzenegger super-fan named Danny (played by Austin O’Brien) ripped a “magic ticket” that projected him into the latest Schwarzenegger franchise film, Jack Slater IV. The biggest problem with the execution of Last Action Hero—beyond its gang-written screenplay having more premise than plot—is that there’s not enough of a distinction between Danny’s own “real” world and Jack Slater’s movie-world. The movie-world is more openly ridiculous, populated by sexy supermodels and walking cartoons, but Danny’s “New York” looks like a backlot, and when Jack Slater and the bad guys cross into it, the fight- and chase-scenes are just as over-the-top as they were in Jack Slater IV. A goodly amount of this parody of violent action pictures plays like a violent action picture.

The same can be said of the Last Action Hero video game: It’s just a video game, with no real twist. Given an opportunity to play with the conventions of its jumping-and-brawling action and maybe even poke fun at sketchy movie adaptations, the developers of the Last Action Hero game shrugged and made something close enough to the settings and characters of the film that it could maybe be called satirical—but only to the extent that the movie is.

Last Action Hero had multiple video game adaptations, for the NES, Super NES, Game Boy, Game Gear, Sega Genesis, and Commodore Amiga. Each has Jack Slater punching his way past generic goons, in locations from the film: a rooftop funeral, Los Angeles traffic, a big premiere. Each version of the game is distinct from the others—sometimes subtly, sometimes drastically. The NES Last Action Hero has the quirkiest variation: a level based on the explosive Jack Slater version of Hamlet that Danny daydreams while in English class.

Otherwise, the biggest differences between all the different Last Action Heros have to do with the quality of the graphics and the responsiveness of the Slater character. The Game Boy version—the one that I own—is the stiffest and most visually muddy. (It’s also the hardest to play, because as more than one YouTube reviewer has pointed out, its first level is the toughest to beat.) But even the most detailed Last Action Hero game is a routine walk-punch-jump-duck affair, featuring a squat little guy who kind of looks like Arnold Schwarzenegger, if he’d been run through a Xerox machine a few dozen times.

In Last Action Hero, Danny frequently tries to convince Jack Slater that he’s living inside of a movie by pointing out that everyone Jack knows has a “555” at the start of their phone numbers, and that Jack can’t say “fuck” because his films are rated PG-13. If Danny wanted to prove that the Game Boy version of Jack Slater isn’t real, he could ask:

- Why is every building you enter made up of narrow corridors, stacked atop each other?

- Why is there a time limit on how long you can spend in any one place?

- Why does accidentally touching a flame send you flying backward 10 feet?

- Why does taking a punch send you flying backward 10 feet?

- Seriously, dude, why do you seem to have the rigidity of a stack of dropped papers on a windy day?

The Last Action Hero game is level-poor—featuring less than a dozen of what it calls “scenes”—but at least it does aim for a little variety. When Jack’s not edging slowly down dangerous hallways, he’s zooming around in a car, and in the grand finale, his objective changes from getting the hell out of whatever tight space he’s in to finding a way back into the movie screen from whence he came. As with the “action Hamlet” level, the theater at the end of the Last Action Hero game is one of the few moments that follows the movie’s lead and embraces artificiality.

The game version of Jack Slater lacks personality—or even character-specific moves—which would be more of a letdown if Last Action Hero had actually become the phenomenon that it was meant to be. Ultimately, the movie Slater is too much of a composite of Arnold Schwarzenegger roles to stand out as a character. (It doesn’t help that The Simpsons’ Schwarzenegger/Lethal Weapon parody, “McBain,” skewers action movie bombast better, and quicker, than Last Action Hero does in 131 minutes.) So maybe it’s apt that Slater became yet another blocky kick-fighter.

The bigger question is: Should Last Action Hero have even been turned into a video game? In the 1990s, video games practically became the starting point for blockbuster licensing, before any posters, T-shirts, or play-sets. But the choice to produce a Last Action Hero game is questionable, given that the movie is sort of a critique of the violence that kids absorb from popular culture. Danny’s depicted as a jaded preteen who’s been numbed to mayhem by Jack Slater movies and cartoons. And yet here’s the Last Action Hero video game: nothing but one shoot-out, punch-out, and fireball after another.

Then again, the film Last Action Hero has just as mixed of a message about violence, trying simultaneously to damn it and sell it. The video game, by contrast, has no message and no point of view. If anything, the game proves Last Action Hero’s point in a roundabout way: By reducing an action movie to a series of nondescript scenes, each duller than the last, the Last Action Hero video game succeeds in making violence uncool.