The Last Days Of Café Leila serves up a family’s history of exile

It’s telling that our comfort foods are often dishes we associate with home, whether that’s a location or point in time. Those familiar tastes and aromas are part of our foundations, our pasts. A sip of some Mexican hot chocolate or spoonful of āsh can take us back to a happier time, or even provide a little solace in a painful present. Chef Donia Bijan previously explored the relationship between food and home in her memoir Maman’s Homesick Pie. The San Francisco restaurateur recalled how she and her family fled their native Iran in the wake of the Islamic revolution, resettling on the West Coast where they were free to flourish. Bijan dedicated the book to her mother, who nourished her love of cooking by sending her to Le Cordon Bleu, where she added French cuisine to her Persian repertoire.

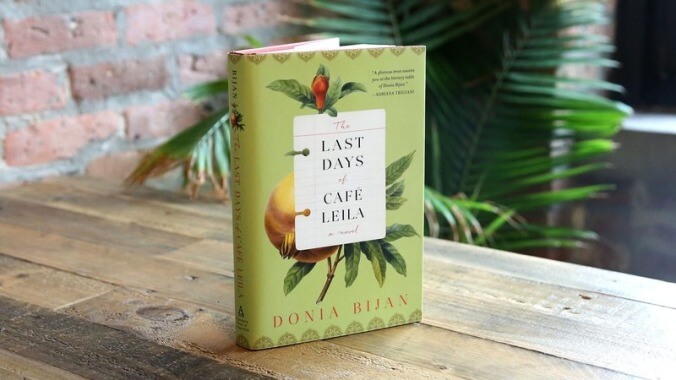

For her debut novel, The Last Days Of Café Leila, Bijan remains in that familiar territory, whipping up a new batch of stories of escape and self-discovery. There’s a whole host of characters and protagonists, and Café Leila shifts among their perspectives throughout. But the book regularly circles back to Noor, a heartbroken Persian-American woman with something of an identity crisis. While in the middle of a divorce from her cheating husband, Noor packs up their teenage daughter Lily for a trip back to Tehran, the first she’s made in 30 years.

Noor’s driven eastward by a desire to avoid dealing with her husband’s betrayal, but there’s also an underlying need to be back on firm ground, which, for her, is the very place she fled as a teen. Wanting to spare them the Islamic state’s oppressive rule, her father, Zod, sent Noor and her brother Mehrdad to California, where his own brother had relocated following an earlier tragedy. They thrive in exile, but there’s a nagging sense that something’s missing. In an effort to resolve her midlife crisis, Noor steeps herself in her culture once more, helping her father tend to Café Leila’s customers, who have their own history with the restaurant—and city.

The novel is composed like an extravagant meal, starting with a bracing aperitif of a prologue before serving samplings of Noor’s longing, Lily’s discontent, and Zod’s desire to give his children a better life. Bijan’s culinary background once again informs her writing, fueling her comparisons between the satisfying simplicity of Spanish cuisine with the ease of courtship in its earliest stages. Her separation features more spartan fare, while her change in scenery is followed by all the complex dishes of her homeland. The story loosens its belt as it goes on, with chapters growing longer and meatier to allow Noor to confront her past and future. Because she’s being pushed out of one and blocked from the other, she doesn’t trust her instincts. So she returns to her childhood state of just watching the action going on in the kitchen.

While never quite delving into the magical realism of works like Como Agua Para Chocolate, it’s clear the author believes food can influence or reflect moods. Borscht is soup for the heartbroken, Noor learns from a relative, because its crimson color illustrates the pain. Or perhaps it’s because the bright flavor acts as a salve. And the pieroshkis Noor is only confident in attempting by book’s end are packed with her family’s regrets and hopes, not just hers. But the gloves come off and the oven mitts come on for a celebration. When Café Leila’s employees and proprietors join forces for memorable feasts, it’s as much an act of defiance in post-revolution Tehran as it is a kind of cultural fusion.

Despite all these savory allusions, Café Leila’s main course is its diasporic tale, which shows multiple generations uprooted. Even after finding some success in the U.S., when Noor’s life gets rocky, all she wants to do is head home. Zod warns her that Tehran has changed, which she comes to see for herself when she takes her angsty, American teen daughter to Iran. The other two generations also feel a bit adrift: Lily is surprised by how little she has in California, aside from her parents, and Zod wonders what he has left to call home. There’s no neat resolution for their doubts; like Café Leila’s owners, Bijan just invites her characters to break bread and share their stories.

Purchase The Last Days Of Café Leila here, which helps support The A.V. Club.