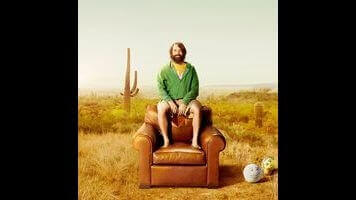

The Last Man On Earth: “Alive In Tucson” / “The Elephant In The Room”

There is nothing else on television like The Last Man On Earth.

This isn’t an exaggeration. There is just not another show that even comes close to what The Last Man On Earth is trying to do, especially in its pilot. Quite frankly, “Alive In Tucson” should in no way work as well as it does. A title card tells us in the beginning that this world exists after “the virus,” but we otherwise don’t get any information about what said virus was or why aggressively ordinary temp Phil Miller (Will Forte) survived it. Even further, The Last Man On Earth is in no rush to answer the question it raises. For 18 astonishing minutes, we follow one person’s struggle to maintain his humanity in a human-free world. That’s it. There is one brief flashback to Phil’s life in “the old world,” and the arrival of Kristen Schaal’s “last woman on earth” at the episode’s end signals where the series might be going for a while, but the vast majority of the Forte-penned pilot rests on his shoulders as Phil goes through all the stages of grief, all by himself.

Oh, but it’s a comedy—and a very funny one at that.

Given the talent behind The Last Man On Earth, it being funny is not a shocker in and of itself. Forte, a uniquely absurd writer and performer, wrote the pilot knowing he could anchor this tricky premise. He has a knack for grounding characters in reality with affable grins and blasé shrugs before yanking them out into chaos with a sudden jolt of anger, pain, or something as unapologetic as debilitating horniness. There is a part of me that’s disappointed with The Last Man On Earth being yet another straight white guy “everyman,” but the combination of Forte’s writing and performance is strong enough to justify it. Meanwhile, the show is also directed and produced by Phil Lord and Christopher Miller of The Lego Movie, 21 Jump Street, Clone High, and Cloudy With A Chance Of Meatballs. Lord and Miller have a very particular style of directing that leans on quick cuts and escalating montages, but more than that, all their projects share a common thematic thread: none of them should have worked as well as they did.

So no, it’s not surprising that The Last Man On Earth is funny. The real surprise is that Fox would gamble not just on a high-concept, but one that finds its comedy in some incredibly bleak material.

Take the cold open of “Alive In Tucson.” Phil, not quite in denial but not quite ready to admit the truth, rolls a bus around the United States in search of another living person. He calls through a loudspeaker hoping that someone, anyone, will call back. When no one does, he takes out a map and crosses the state off, until he finally looks down and sees a country covered in ominous black X’s. He blinks, almost calm, and then we cut to outside the stranded bus and hear Phil scream. Forte draws the screech out long past its natural end so it goes on, and on, and on, and while it does that thing where something goes on so long the mere length of it becomes hilarious, there’s also a very real despair there. Phil—as far as he knows—is alone.

From that moment on, The Last Man On Earth immediately becomes one of the most singular shows on television. It manages to be very funny, letting Forte stretch his physical comedy muscles in a series of montages in which Phil embraces his id. He decorates a fancy home he could have never afforded “in the old world” with souvenirs from his cross-country quest for humanity: Academy Awards, the eagle rug from the Oval Office, a massive dinosaur skull, and countless priceless paintings. He wears Michael Jordan’s jersey and yells at Cast Away that he will “never ever talk to a volleyball… balls are for fun, man!” Then as if to prove his point, he stands across from a machine shooting tennis balls in a full suit of armor. He goes bowling in a parking lot, starting with regular bowling pins, then a clump of glass lamps, and then full fish tanks stacked on top of each other. Lord and Miller are fans of a longer shot throughout the series, and the one that sits on the waiting fish tanks only to have Phil back into the frame with a pick-up truck full of bowling balls is one of the pilot’s biggest laughs. For a little while, Phil accepts his status as the only man left standing as an excuse to do all the stupid shit he could never have done before, and for a little while, everything is awesome.

As Phil keeps living and keeps holding out hope that someone else will find him, though, his conversations with God get more and more hopeless. Phil praying quickly becomes Phil using God as a way to talk to someone, anyone. It’s a handy device that Forte takes full advantage of—I mean, of which Forte takes full advantage. Phil starts off by apologizing for “all the recent masturbation” before chuckling, “but that’s on you,” like he’s old friends shooting the shit with God instead of a lonely man trying to work through his feelings about being the sole survivor of a completely devastating virus. When Phil exhausts his energy letting loose with fish-tank bowling and mixing spray cheese with $10,000 bottles of wine, he takes his anger out on God. “Guess what?!” he shrieks at the ceiling, “I don’t even care! I don’t need people! I’m gonna be just fine!”

Smash cut to: “FIVE MONTHS LATER.” To sell Phil’s despair, Forte’s demeanor swings between existential dread and an upbeat mania. Phil can’t decide whether he is, in fact, dead or alive. He emerges from the pile of trash that’s now his house, exhausted with the effort of staying alive, and goes about yet another day of trying to keep himself occupied with just himself. He wades through oceans of plastic bottles. He fills a kiddie pool with margarita mix, pours salt around the rim, and lies in it with dead-eyed bleariness where he once might have splashed around with unencumbered joy. He stands in front of the tennis ball machine with that same suit of armor on, but it now feels less like wish fulfillment and more like self-destruction. Where Tucson once felt like his sunny retirement spot, it’s now a desert blanched of color. It’s no longer a playground; it’s a vast emptiness that’s devoid of any sign of life, whether that means human bodies leftover from The Virus or even a single sign of animal life.

Instead of talking to God, Phil turns to an assortment of—you guessed it—balls. Five months from where we left him, he doesn’t even have the one volleyball friend he swore he would never need, but a long, long roster of imaginary ball friends. Phil walking into the restaurant he’s adopted as his local bar and asking each ball in turn if they want some whiskey follows in the cold open’s footsteps; it’s prolonged and it’s hilarious, but also incredibly sad.

This attempt to create a community out of unresponsive objects leads to the pilot’s most uncomfortable and deeply effective scene. With Gary the volleyball in tow, Phil pulls up to a storefront and faces a female mannequin he’s been staring at for months. He talks at Gary’s blandly smiling face about his crush before finally going up to the window, shooting it clear, and shyly approaching the mannequin. Forte keeps Phil’s side of the interaction as grounded in a real nervousness as possible, which makes the mannequin’s lack of reaction through his small talk and halting kiss all the more crushing. Then, Phil goes to shake her hand, and it comes off in his. We sit in the devastating silence of this moment, when Phil finally has to accept the fact that this mannequin is not and never will be the human he craves. He crumbles to the curb, looks to the sky, and addresses the god he’s at turns tried to ignore and defy in a resigned voice barely above a whisper: “You win.”

And so Phil decides to kill himself.

It would really surprise me if Forte didn’t look to Groundhog Day at least a little when writing The Last Man On Earth. Harold Ramis and Danny Rubin’s pitch-black comedy also explores the existential crisis that comes out of being stuck in a constant, repetitive loop. It even manages to wring humor from an extended sequence in which Bill Murray’s self-loathing reporter (also a Phil) tries to kill himself, over and over. Both Groundhog Day and The Last Man On Earth play out a variety of scenarios before their main characters take a turn for the worse, so that by the time they decide to end their lives we have lived with their pain enough to understand what brought them there. The Last Man On Earth has a trickier problem to navigate, though. Murray’s Phil learned to love life again by loving other people; Forte’s Phil doesn’t have quite the same opportunity.

While “Alive In Tucson” is so impressive for being a largely one-man performance, it also portrays Phil’s loneliness in such a way that it makes the audience feel just as claustrophobic as he does. It’s impressive, especially because it make us feel just as relieved as Phil does when he sees a curl of smoke in the distance and slams the brakes on his suicide mission.

While it was unlikely that The Last Man On Earth was ever going to try and sustain a series based around a single person, it still comes as somewhat of a surprise when he pulls up to someone else’s campsite. It’s even a little disappointing, since Forte turns in such a stellar performance throughout the pilot. When the “someone else” turns out to be a softly-lit Alexandra Daddario, it feels too easy—which, of course, it is.

No wait, sorry—which it is, of course.

Having Phil wake up to Kristen Schaal’s Carol is a bold choice. First of all, it throws Phil into startling and unflattering relief. After years of wandering the earth all by himself, it’s natural that he would start concocting fantasies of finding a stereotypically gorgeous babe who would cradle his head and sing the Ghostbusters theme with him. It is less understandable that Carol immediately repulses him. She might not be a softly lit Alexandra Daddario, but at the end of the day, she is still a person. It was easier to see Phil longing for a woman as Phil longing for companionship, but his disappointment with Carol makes him less sympathetic—but maybe more realistic. Sure, he’d like to have a woman he can get along with, but he also really, really just wants to get laid. To be clear, I’m not ideologically opposed to Phil reacting to Carol in a questionable way. It’s far more interesting to let the last man and woman on earth not just find each other, but hate each other. Pre-virus Phil and Carol would never have gotten along, but for now, they don’t have anyone else with whom to get along (are you happy now, Carol?!).

A less ambitious show would have let the pilot handle the brunt of the existential crises so that the series could go on to purely have fun with this brave new world that has no people in it. Instead, the second episode (“The Elephant In The Room”) continues to ask hard and fascinating questions. While Phil assumes not having to deal with other people means he can embrace a lawless and shameless existence, Carol still operates by all the previously existing rules. She bristles when Phil runs through stop signs and gapes at the paintings he lifted from museums. She constantly corrects his grammar to the point where it’s unclear whether she actually knows what she’s saying (Phil: “what do you need that gun for?” Carol: “I think you mean ‘out for what do you need that gun?’” Phil: “That can’t be right”). Then, when they go to the store, she demands that he park in a non-handicapped space.

I was with Phil at first, because who could care about traffic when “traffic doesn’t exist anymore”?! But Andy Bobrow’s script makes Carol’s approach to this empty new world far more complicated than just being strict. I wasn’t necessarily surprised; Bobrow wrote “Mixology Certification,” a controversial Community episode that’s nevertheless one of my favorites. It’s an unusually dark chapter, filled with as many uncomfortable truths as jokes. For me, Bobrow showed an impressive skill for balancing bleakness with humor, and he does the same in “The Elephant In The Room.” Just look at the fight Phil and Carol have over him parking in that handicapped parking space:

Carol: “What’s next? Are you gonna burn down a church?”

Phil: “No, I would never burn down a church!”

Carol: “Why?”

Phil: “Because it’s a church.”

Carol: “And this is a store, and that is a handicapped parking spot.”

It’s not just that Carol is a stickler for the rules; it’s that she thinks letting go of the world they had before could also mean letting go of her humanity now. (And if you think she’s operating in extremes, take a look at Phil’s hoarder house and tell me he’s not doing the same.) The episode unfortunately moves a little too quickly from there to Carol unraveling, but it’s still hard not to feel a pang when Carol deadpans from her toilet fountain, “we weren’t chosen—we were forgotten.” The ensuing sequences in which Phil buckles down to get running water for her, she forgives him, they have dinner, and she makes him propose marriage (so any kids that come out of possible “lovemaking” aren’t born out of wedlock) are, again, slightly rushed.

As as the credits roll on the second episode, though, we have a much better idea of what The Last Man On Earth could look like from here on out. Or a much better The Last Man On Earth from out here idea could look. Or something. (Dammit, Carol!) Anyway, it’s unclear for now whether Phil and Carol really are the last man and woman on earth like they say (there have to be some people wandering around Europe, Africa, Asia, and Australia, right?), but their manic grief is the perfect showcase for Forte and Schaal. If we’re going to be stuck with just two people for the foreseeable future, I’m thrilled that it’s them.

Stray observations:

- Welcome to weekly coverage of The Last Man On Earth! I’m thrilled to be covering this show, as evidenced by the many, many words I wrote on the subject.

- I was expecting far more flashbacks, but I’m more impressed that they practically don’t use any. That’s definitely Jason Sudeikis in Phil’s family picture, though, so I’d wager we’ll get at least one with him.

- Like I said, there are so many questions I still have about The Virus. Does it actually disintegrate bodies? Did it kill all the animals? Will they have to be vegetarians?! (This last question is the most important.)

- I hereby nominate Will Forte to sing the Ghostbusters theme for the upcoming reboot.

- Phil to one of his many ball friends: “That’s really homophobic, Bryce. Even for you.”

- “I apologize to the cast and crew of Cast Away. They nailed it.”

- “There’s really no wrong way to use a margarita pool.”