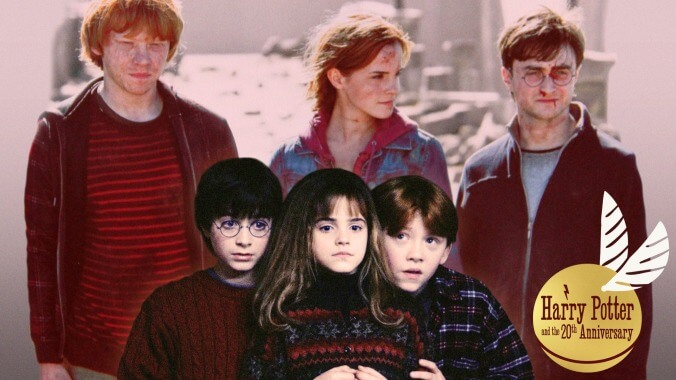

The legacy of Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone and J.K. Rowling—20 years later

The A.V. Club grapples with the idea of whether it’s possible to reconcile love of Harry Potter with disdain for its creator

Image: Graphic: Libby McGuire

Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone was originally published in 1997. Although the book series made a splash upon its release, it wasn’t until the film came out in 2001 that Harry Potter really began its ascent into the mainstream pop culture stratosphere. Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint, unknown children at time of the premiere of Chris Columbus’s film, quickly became household names. Author J.K. Rowling herself—and her rags to riches legend—was elevated to a sort of godlike figure by Harry Potter-loving diehards.

But now it’s 2021, and in the 20 years since the film’s release—and with the unstoppable rise of the Marvel Cinematic Universe—Harry Potter’s overarching impact of pop culture and entertainment is waning. What’s more, J.K. Rowling and her social media presence have also become impossible to ignore. Rowling continues to use her platform to make transphobic comments and spread transphobia—even after being called out on it multiple times and by multiple people.

In a roundtable conversation, members of The A.V. Club revisit Harry Potter’s lasting legacy and grapple with the idea of whether or not it’s possible to reconcile one’s love and appreciation for Harry Potter with disdain for its creator.

What do you remember about your first time watching Harry Potter And The Sorcerer’s Stone?

Matt Schimkowitz: I was very late to Harry Potter. The books dropped when I was at my most “If it’s popular, I hate it” phase. I didn’t end up reading the books or seeing the movies until the Order Of The Phoenix movie came out in 2007. I think Sorcerer’s Stone was the last or one of the last movies I rented from Blockbuster, so that’s something.

One thing that struck me about Sorcerer’s Stone was how slow it was. The book was such a breeze, but the movie seemed to stop and gawk at every detail it included. Still, some moments really were—and I’m sorry—magical. The iconic shots of the boats approaching Hogwarts, the Great Hall, Ron and Harry wishing each other “Happy Christmas”—all of it was so inviting and so lovely that they overshadowed all the film’s shortcomings—namely the pacing, the Quidditch, and the troll.

Gabrielle Sanchez: I was 4 years old when the first installment of Harry Potter arrived in theaters in 2001, so my experience watching the film for the first time most likely took place during one of the former ABC Family’s many marathons on cable. I remember being fearful of the adults in the films and grossed out by the snotty three-headed dog named Fluffy.

Shanicka Anderson: The first time I saw the film was in theaters—but there’s kind of a twist. I originally went to the theater that day with my uncle and cousins, and even though I begged them to let us see Sorcerer’s Stone, they all wanted to see Martin Lawrence’s Black Knight. I was outnumbered. When that movie finished, though, another showing of Sorcerer’s Stone was about a 1/3 of the way through. So we snuck in. It was my first (and only) time sneaking into a film.

What kind of effect has Harry Potter had on you?

Matt Schimkowitz: I’ve always been a bit of a Potter skeptic. Some entries I loved (Half-Blood Prince, Prisoner Of Azkaban), others I loathed (Chamber Of Secrets). So I wouldn’t say that it had much of an impact on me. I could live without it.

William Hughes: I’m older than some of my colleagues in this conversation, so I didn’t catch the Hogwarts Express until I was a teenager, when rumbles about the franchise started bubbling up from some of my younger friends. (Prisoner Of Azkaban had just come out, so I must have been 15 or so.) What struck me, both then and now, was how welcoming a worldbuilder Rowling was in those first few books. By that point, I’d spent plenty of time with fantasy and sci-fi novels that were obtuse, cold, and endlessly bogged down in their own minutiae; to encounter a book that was so laser-focused at inviting the reader in—with a premise that remains functionally unbeatable as far as tween power fantasies go—was more or less irresistible. My love affair with Potter didn’t last especially long. (The infamous “Long Summer” between the fourth and fifth books did a number on my enthusiasm.) But it was a special set of memories, regardless of how the franchise twisted and mutated after I left it. At least until, well, you know.

Gabrielle Sanchez: I wouldn’t say that Harry Potter (either the books or the films) has made an impact on my life, personally. It’s been something a lot of friends and family have enjoyed over the years, but I never felt connected to the series in the same way others do.

Shanicka Anderson: Harry Potter is my personal pop culture comfort item. It’s one of those things I always come back to—especially around this time of year. The moment the weather drops below 65 degrees. I’m like, “Ahhh, okay, time to go back to Hogwarts, my ancestral home.” Having the movies on (even when they’re just playing in the background and I’m not paying attention) or occasionally re-reading the books feels so much like home and the holidays. I’m also a person who’s pretty big into fandom and back in college (and even now) I met and bonded with a lot of my closest friends through a mutual love of Harry Potter. We were also really into StarKid Productions’ “A Very Potter Musical” (which featured a baby Darren Criss!), which seemed absolutely genius at the time.

How would you describe the cultural significance of Harry Potter?

Matt Schimkowitz: I would describe Harry Potter’s cultural significance as waning. It undoubtedly transformed the types of stories that were told in the 2000s, bringing in more YA-focused fantasy to the mainstream. There was some handwringing about that at the time, but I think it’s a good thing that kids were reading something they liked. Go figure.

As is the case with many franchises, its creator’s politics have profoundly affected how the culture views Harry Potter now. Rowling’s incessant transphobia has taken some of the sheen off the Hogwarts Express.

Even if you want to separate her from the conversation, the cultural nonexistence of the Fantastic Beasts series shows Rowling’s and Potter’s slipping appeal. That’s not due to so-called cancel culture; Rowling’s still able to write whatever she wants and be rewarded handsomely for it. It’s due to a lack of quality. Is there anyone clamoring for a third entry? It doesn’t seem like it. The consensus is Harry Potter is good and the “Wizarding World” spin-offs are forgettable.

William Hughes: If Harry Potter isn’t the last new thing that every single person on the planet needed to have a definitive opinion about—the MCU has given it a decent run for its money over the last decade—it’s at least in the healthy running. And as a billion self-identified Hufflepuffs and Slytherins could attest, Harry Potter isn’t just a media property; it’s a way to see yourself reflected in the world. The butterbeer and the theme parks and the godawful novelty jelly beans might come and go, but the story’s core beats—its reinvention of the classic Kirk/Spock/McCoy power trio, its iconography, even the lazy-but-it-sounds-fine Latin of its spells—has seeped inextricably into the groundwater of Western culture. But it’s the way it lives in the heads of the kids who grew up on it, in the parents they shared it with, in the friend groups that formed from it, that makes it elemental to understanding how we think and act today.

Gabrielle Sanchez: It spurred one of the largest fantasy communities and commercial enterprises, on par with Star Wars. It undoubtedly means a lot to a lot of people, allowing a form of escapism and fun.

Has your relationship with Harry Potter changed in the wake of J.K. Rowling’s transphobic comments?

Matt Schimkowitz: I was already critical of Harry Potter, and Rowling even more so. I already hated her tweeting about the pooping habits of wizards and for retconning plot points, like Dumbledore being gay. If you intended that to be a part of the book, why not include it? Instead, it read like she was either hedging or pandering.

But more importantly and alarmingly, I do think it’s abhorrent behavior, doubly so considering her social standing. To sit on high and spew such hateful, ugly, and dangerous language and then pretend that you’re the victim is despicable.

Moreover, her behavior is a betrayal to those who found strength in her work, especially in the LGBTQIA+ community. Given her reach, I’m sure there are plenty of people who found a lot of courage and comfort in Harry Potter. To have thrown it back at them like this is really gross and I hate it. So, yeah, it’s definitely soured me on her and, by proxy, her work.

William Hughes: It makes me sad, but not for myself. (Okay, a little for myself; my favorite Newswire I ever wrote, about Rowling’s utterly wack assertion that wizards used to shit on the floor and then magic it away because they couldn’t be bothered to invent toilets, is now irrevocably tainted by association.) But, seriously: I’m genuinely sad about all the kids, past and present, who gravitated to a book series that told them they could be special—and who now have to reconcile those feelings with the author taking some of them aside and saying, “Oh, but not you.” It rots the entire enterprise; it makes a lie out of every imagined Hogwarts letter that ever flew through a kid’s mental windows. It also makes any financial support of the franchise totally indefensible, at least for me; all I see when I look at a Sorting Hat now is a funnel sending money straight to a woman who’d rather double down on her own skewed beliefs than take the time to listen to the people she’s hurt.

Gabrielle Sanchez: Over the last few years, many things have soured any potential relationship with Harry Potter. In addition to her repugnant attacks against trans women in attempts to undermine their womanhood, Rowling’s been ambivalent about many other points of valid criticism against the series, including the lack of queerness and holistic representations of people of color. Her insistence on making Dumbledore a queer character retroactively made little sense to me and felt like a way to exploit a queer identity to revive interest in the books. Additionally, she continues to make money off of expanding the Harry Potter universe, which is why supporting anything new coming out is completely off the table for me.

Shanicka Anderson: I was never one of those Harry Potter fan who idolized J.K. Rowling, but her inability to stop tweeting and her constant doubling down still feels like a betrayal. So many trans and nonbinary people I care about found solace and community because of Harry Potter and for her to spew constant vitriol at this same group of people is, at best, upsetting and, at worst, extremely violent. However, because I never felt any sort of hero worship for Rowling, she wasn’t able to completely ruin the series and its characters for me. It’s just that now I’m less inclined to tell people I’m a Harry Potter fan. It’s now something I carry with more than a little bit of shame or it’s something I’ll admit it with a huge disclaimer: “Okay, yes I like Harry Potter but…” And, as my colleagues have pointed out, I’m also no longer okay with spending my own money on any officially licensed Harry Potter merch. Anything I have or buy now is strictly fan-created.

When it comes to Harry Potter and Rowling, why do you think more people are willing to separate the art from the artist?

Matt Schimkowitz: Try as we might, we can’t help but like what we like. We’re drawn to the art we like instinctively. We can refine our palate or grow more sophisticated in our tastes, but we all gravitate toward what interests us at the end of the day. And Harry Potter, for a lot of people, is where that journey began. Like Wuthering Heights or Star Wars or John Wayne movies, it was formative to how millions understand and appreciate art. Something like Harry Potter had a hand in helping millions of readers and moviegoers realize what they like. It’s not so easy to just dismiss something like that entirely.

The author, on the other hand, can be ignored. Once their work is out in the world, it no longer belongs to them in many ways. Fans can do with it what they choose.

William Hughes: There’s a point when any story—even one written by a single person—can get out of an author’s hands. So many people have poured so much of themselves into Harry Potter over the last 24 years: fan artists, fan writers, cosplayers, and just plain old fans. They have changed it through observation, and participation, bolting whole universes of meaning onto it that extend far past what Rowling ever intended, or even could have conceived. To destroy all of that beautiful scaffolding, just because the foundation has revealed itself as rotten—that’s a hard thing to do. How much you let the author affect “your” Harry Potter is a personal decision, of course. (I can’t bring myself to forget how much Rowling continues to profit from the series’ endless propagation.) But wanting to hold on to wonder is a difficult impulse to shame.

Gabrielle Sanchez: I think it’s hard to wholeheartedly reject something so pivotal to someone’s childhood and understanding of self. Some people have spent their entire lives loving the Harry Potter franchise, building community and leaning on it for support. When looking at something like films, I also think it’s easier to disassociate the artist because there’s so many other people involved. It can become more about the actors and characters versus who actually created them. Also, Rowling’s open transphobia is something that began to transpire just in the last couple of years, long after the film and book series were complete. To revisit a long existing work is different than to continue financially supporting an artist who is a known abuser and in Rowling’s case, a big ol’ TERF.

While I may not be a Harry Potter fan, I am an avid Buffy The Vampire Slayer enthusiast. Even as the allegations against Joss Whedon have arisen over the last few years, Buffy remains one of my regular rewatches, and this is something I have to regularly reckon with. As a character, Buffy means an indescribable amount to me and it would be difficult to step away from the series and never watch it again, so I do understand people’s cognitive dissonance on the subject.

Shanicka Anderson: As my colleagues have pointed out, Harry Potter is one of those series where—because the fandom is so robust and people have created so many incredible fan works—it feels like it no longer belongs to Rowling. Some of the ways we, as fans, have reclaimed Harry Potter (i.e., through race-bending, Harry and Hermione are POC in my head canon, and providing a community for so many young queer and trans kids) are more impactful than anything Rowling herself has done. As a result, it feels like Rowling doesn’t really “own” or even “deserve” these characters or universe anymore. There’s no easy way to reconcile Harry Potter with Rowling (and even if I was able to do so, as a cis person, it wouldn’t cool for me to go around proudly boasting about how I’m able to forgive and forget). The way I think about Harry Potter now is like, “Wow, look at this cool series I love that just happened to spring into existence with no known origin!” For me in 2021, “loving Harry Potter” means loving the memories, rereading and engaging with various fan works, and celebrating the very queer community I’m a part of and have built around it.