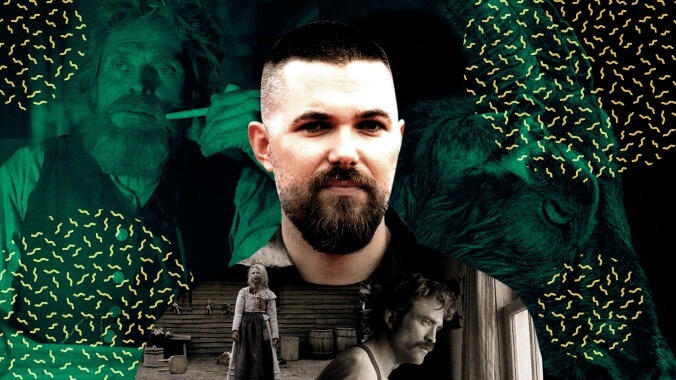

The Lighthouse’s Robert Eggers: “Nothing good happens when two men are trapped in a giant phallus”

Image: Photo: Lou BenoistGraphic: Allison CorrPhoto: The LighthouseScreenshot: The Witch

There’s no point in asking Robert Eggers about historical authenticity in his films. First of all, both The Witch and The Lighthouse have supernatural creatures in them, making the question ridiculous in context. But Eggers has also made it clear that he’s not interested in doing anything else. It’s like asking a comedian why they tell jokes, or an action star why it’s important that they do motorcycle jumps while skyscrapers explode behind them. The obsessively detailed, psychologically loaded period pieces he makes are just an extension of who Eggers is, both as a filmmaker and a person.

Eggers’ latest film, The Lighthouse, stars Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson as lighthouse keepers in 1890s New England whose combative relationship turns hallucinatory and violent after they get stranded together by a storm. It’s a funnier film than The Witch, and Eggers has a good sense of humor about it as well: At a Q&A about The Lighthouse at this year’s Fantastic Fest in Austin, he quipped that “there would have been a lot less masturbation and mermaid genitalia if this was an old movie.” He also said that the film was inspired by a 19th-century Welsh folktale about two sailors, both named Tom, stuck together in a lighthouse. We asked Eggers for more details on that, as well as his interest in archetypes and folklore, Willem Dafoe’s Miltonian monologues, and how seagulls are smarter than you might think.

The A.V. Club: I wanted to ask you about the story that you referenced that inspired the film.

Robert Eggers: It’s often referred to as the Smalls Lighthouse tragedy. It’s not [the same as] my story: The ending is very much like “The Tell-Tale Heart.” The old guy dies, and the young guy’s tormented by fantasies that the corpse has come to life and keeps rapping on the lighthouse. Basically, there were two lighthouse keepers, one older, one younger, both named Thomas. The younger one had a sordid past and was known for violence, and in there and they were known for having rows, and they got stranded on their lighthouse station during a storm.

AVC: Was this reported in newspapers? Was it a historical event?

RE: It was a historical event from the early 19th century—maybe the 1820s? (According to the BBC, the Smalls Lighthouse tragedy took place in 1801. —Ed.)

AVC: It sounds like something from a penny dreadful.

RE: For sure the elder Thomas died, and for sure they were trapped on the lighthouse station for a long time. Beyond that, how much of it is myth and how much is fact, I’m not sure.

AVC: Both this and The Witch are stories about someone who is stuck in an isolated place with a corrupt authority figure, and forbidden knowledge is at the edges of the story. Is the Adam and Eve, biblical aspect something you’re consciously working with?

RE: In every story told, someone needs to eat the forbidden fruit. They need to transgress the rule for the story to be interesting. Obviously, these two films have a lot of similar themes and motifs. That’s not intentional, really, but most authors do have a primal narrative. Charles Dickens wrote the same book over and over—well, he did also write A Christmas Carol, but in general, he had one story to tell. That may or may not be true with me, we’ll see. But I’m sure that if I made a movie with many, many locations, there would still be a lot of the same stuff going on.

Part of the reason for the single location in both films was just because I could afford to do it that way. And then you get the opportunity to explore this pressure cooker situation where people can go to these emotional extremes, which is also fun and interesting.

AVC: That’s drama, right?

RE: Absolutely.

AVC: That leads into the building of the lighthouse set in Nova Scotia. How many crew members did you have out there?

RE: The Nova Scotia crew was incredible, but I know that there came a point where Craig [Lathrop], the production designer, was saying, anyone who could lift a hammer in Nova Scotia was on [the project]. We eventually had to bring carpenters on from Prince Edward Island because we just didn’t have a lot of time to build everything. You never do with a movie. And three nor’easters blew over while they were building, so occasionally things slowed down. [Laughs.]

AVC: Out there, the weather really dictates what you can and can’t do, right?

RE: Absolutely. There’s footage of waves crashing over the lighthouse as it was being built.

AVC: Did you end up losing any time because of all that?

RE: I think we started on time. The movie did go over schedule a little bit. Shooting in the stormy weather slowed us down a lot, and there were a lot of tiny scheduling knots because of weather. It was actually more, because if it was a sunny day, we couldn’t do anything, right?

AVC: You can’t be dragging a rain machine out there.

RE: We did use a rain machine for some of the more placid rainy moments. But you still need an overcast sky to make it look realistic.

AVC: Are you afraid of birds? They show up in negative ways in both of your films.

RE: If you’re not afraid of seagulls, then you’ve never met one. I don’t like it if, say, a pigeon flies too close to my face, but I don’t have a bird phobia, particularly. My wife does, but I don’t. For me, it’s more that animals are a part of folklore, and sea birds are a major part of nautical folklore. So they needed to be in this film. And ravens were part of witch lore, so they’re part of that world.

AVC: You mentioned the gull actors you used in the film were from England, and that they’re the last trained seagulls in the world. What’s that about?

RE: The herring gull, which is like the common everyday seagull, is protected. So these three gulls we used in the movie—my understanding is that they were injured, and so they were fostered by this gentleman. And because seagulls are really very smart, and they’re used to doing stuff and being active, in order to make sure that they’re happy and not depressed, suicidal birds, they train them to do tasks to keep them occupied. And so these three birds were sort of grandfathered in, because they were already around human beings.

AVC: Like if a baby bird falls out of the nest, you’re not supposed to touch it.

RE: Yeah. These birds were government-sanctioned to be saved and help out.

AVC: I didn’t realize seagulls were so intelligent.

RE: I was concerned, actually—some of my New England coastal friends told me, “Seagulls are dumb as hell. The woodpecker is the only animal that’s dumber than a seagull because they spend their day banging their head against a tree.” But a friend of mine who does falconry said, “The seagulls are going to be smart. You’re going to be fine.” And they were incredibly intelligent.

AVC: What were their names?

RE: Lady, Tramp, and Johnny.

AVC: That’s honestly adorable.

RE: And one of them was better at singing. One of them was better at pecking. They all had their speciality.

AVC: A witch and a sailor are both folkloric archetypes, and they’re very gendered archetypes as well. Was there any intention in breaking these archetypes down in terms of gender?

RE: I’m not really in the habit of intending anything. [Laughs.]

AVC: So you’re just drawn to certain subject matter?

RE: Yes, but obviously, I don’t live in a vacuum. So what’s going on in the world is going to come out. With The Witch, I wasn’t like [In a booming voice], “Well, ahhh, I got a good night’s sleep. I’m going to sit down and write me a feminist movie.” You know? I had an atmosphere, which was early New England, and I wanted to explore witches. Do I also see that movie through a feminist lens now that it’s done? Yeah.

And then with this movie, I wasn’t like, “Now I’m going to write a movie about toxic masculinity.” But as I’ve said may times, nothing good happens when two men are trapped in a giant phallus. So obviously that’s what’s going to happen in [the lighthouse].

AVC: It does seem very inevitable between them. So, you didn’t sit down and go, “I’m going to write a movie about toxic masculinity.” But at what point did you start to recognize that that’s what the story is about in some ways?

RE: When my brother and I got all the way through [the script] the first time, we were like, “Yeah, that’s what’s going on.”

AVC: You’ve said previously that Willem Defoe was very comfortable with the rehearsals you did, and Robert Pattinson wasn’t, and that you kind of played on that. Can you talk about that?

RE: I wasn’t trying to make Rob ill at ease—

AVC: You weren’t trying to pull a Stanley Kubrick.

RE: I don’t think that’s respectful to human beings. But it is interesting. The camera sees what is already there, and it doesn’t lie. I think Willem and Rob both had difficult days. We all did. But I would say that there are certain things about my approach that Willem really liked, and there were certain things about my approach that Willem really hated. Same thing for Rob. But I think that the rehearsal part of it was something where Willem and I we were on the same page. Not that Willem Dafoe really needs to rehearse! But for this particular film, he understood why that was something that was important to me.

AVC: He’s got some meaty chunks of dialogue to chew on. Is that based on anything in particular? Because it has a very romantic poetry, kind of sea shanty rhythm to it.

RE: Both of their dialects were heavily researched by my brother and I. The faux-Shakespearean, Miltonian stuff that sounds like Melville doing an Ahab-inspired monologue—I can just kind of write that now, because of some other things. The more naturalistic sailor dialogue is where I really needed to pull from sources.

AVC: That is the exact opposite of what I would have thought.

RE: I mean, but why would I know nautical slang and nautical terms? I might, but I don’t. But I do read early modern English poetry for pleasure.

AVC: So you’re just really steeped in that cadence.

RE: Yeah.

AVC: Are you working on anything new right now?

RE: I mean, I’m always working on something.

AVC: Anything you can tell us about?

RE: No, no, I can’t right now. But I hope it gets made, and it takes place in the past again. I’ve got my heads of department from the last two films with me again, so, you know, think happy thoughts. [Since this interview was conducted, that project has been revealed as The Northman, a “Viking revenge saga” set in 10th-century Iceland. —Ed.]

AVC: Can we expect similar things in terms of drawing from archetypes and folklore and certain periods and settings?

RE: That’s all that I’m interested in. I don’t know if I’m going to always make horror movies. The thing that I’m currently working on is not [horror]. But I know enough to know that unless I’m on set saying, “action,” I don’t know that that’s the next movie I’m making. But who knows? I might be, against my better judgement, talking to you in five years about the third and final film in the New England horror trilogy. But that’s not what I’m doing [now].

AVC: It seems as though the style you’re developing is what you’re primarily interested in.

RE: And mythology. I’m not going to do romantic comedy or a contemporary action movie—that I can see, anyway.

AVC: I think it would be interesting to see what you did with something like that, but I also see why it wouldn’t necessarily be appealing.

RE: And also, because I like creating these worlds, it’s just not fun for me to show up at a location and shoot it. I did a short film called Brothers that takes place in the 1960s… on a farm… in New England. And in some ways it has the best texture of all my pieces, because we didn’t have to build the farm, and we found old clothing that already had patina that we could add to, so we didn’t have to do any of that artificially. That is great about location work, for my taste. But the act of me and my collaborators building the world from scratch is so fucking enjoyable.

AVC: So the whole process is of a piece to you? As in, building the location is an essential part of it?

RE: We’ll see. Obviously, you know, if I tried to get a medieval knight movie [made], I wasn’t building castles. But short of building castles, anything that I can afford—actually, Arthur Max has done it for Ridley Scott a few times, but you know what I mean. If I could build everything, I always would.

AVC: The further back in the past you go, the more you have to build from scratch.

RE: I think it depends. I mean, there isn’t a lighthouse station from that period that is intact the way we had it [in The Lighthouse]. But those buildings exist. The farm that we built for The Witch, those kinds of farmsteads don’t exist. Let’s say everyone in The Witch didn’t die. They would’ve taken that house and they would have built onto it. And then they would have eventually had clapboards that were more even. And they would have gotten rid of the thatch roof, and they would’ve had shake shingles on the roof, and they would’ve put in a brick chimney eventually. So even if there was a house that may have started like that, it doesn’t exist anymore.

The Lighthouse opens in select theaters on October 18, with a nationwide expansion planned through October. You can find a theater near you here.