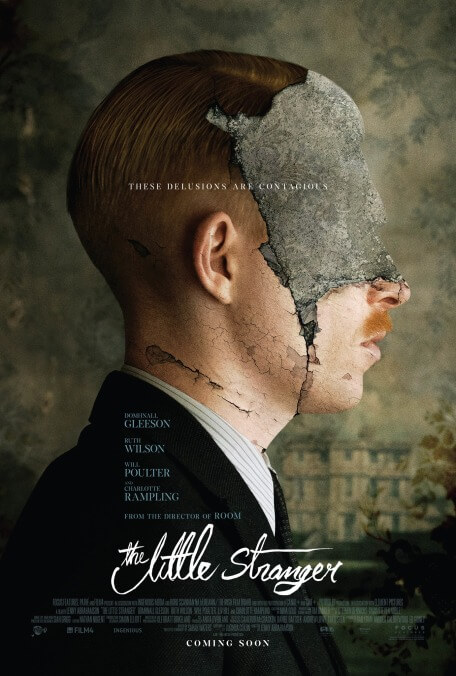

Adapted from a novel by Sarah Waters, Welsh author of sapphic Victorian romances like Tipping the Velvet and Fingersmith, The Little Stranger unfolds chiefly from the perspective of an outsider: the country doctor Faraday (Domhnall Gleeson), who comes to Hundreds Hall to attend to a sick housekeeper, only to discover that she’s not really sick, just spooked by the cavernous, rundown manor itself. “This house works on people,” Mrs. Ayres grants. Roderick, meanwhile, can’t shake the feeling that some dark presence looms over the estate. Is it the spirit of his long-dead sister, or just all in his fractured mind? The Little Stranger comes on like a throwback to British psychological-horror classics like The Innocents and The Haunting. But it’s got more on the mind than another game of Ghosts Or Just Crazy. What really haunts the Ayres is the specter of a bygone high society; if Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Castle was a nostalgic symbol of an aristocratic age, Hundreds Hall is a crumbling tombstone for the same.

As a man of science, Faraday fits the archetypal profile of the rational outsider, ready to debunk a supernatural explanation but confronted with occurrences he can’t readily explain. But he, too, is tormented by the place’s legacy. His mother, we learn, was once a maid at the manor, and repeated flashbacks to a childhood memory of the estate indicate the spell it cast over him. Is Faraday’s growing friendship-or-maybe-more with the pragmatic Caroline, who the locals dismiss as a damaged spinster, just an extension of his deepest social desires? Gleeson, who can do stiffly milquetoast better than almost any actor working today, is perfectly cast as the picture of English repression, all subdued emotion and unyielding formality. (He could do wonders as a younger version of the loyal, besotted butler in Remains of The Day.) The Little Stranger, though, allows Gleeson to peel back that polite-society politeness to find something more troubling underneath. One is reminded of what Abrahamson did with the actor in his offbeat music comedy Frank, warming us to his underdog affability, only to reveal a jealous, exploitative culture vulture.

When The Little Stranger hit bookstores in 2009, it was seen as a change of pace for Waters, an unexpected dabble in Gothic horror. Yet as in Fingersmith—as well as Park Chan-wook’s gonzo adaptation, The Handmaiden—her story depends on a shattering of expectations about the characters, which in this case happens in slow motion rather than through twisty rug-pulls. Likewise, while a sprawling mansion is a much more spacious setting than a cramped tool shed, The Little Stranger isn’t so different from Abrahamson’s Oscar-winning Room in its vision of imprisonment and possessiveness. The director expertly evokes a postwar England without a lot of fuss, sustains an atmosphere of quiet unease, and uses composition to link the physical spaces to the psychic ones. It amounts to his most controlled, elegant filmmaking, and the classiest portrait of paranormal activity to make it to theaters in ages.

That said, very little of the film qualifies as scary. Not that it’s really aiming for that; most of the violence happens off camera, its aftermath given precedence. In truth, The Little Stranger is barely a horror movie at all. It’s more of an impeccably crafted chamber drama with a supernatural bent, like Edith Wharton by way of Shirley Jackson. That may be a tough sell for audiences used to ghost stories that operate as funhouse rides, springing scares on them every few minutes. But the movie, like towering Hundreds Hall, casts its own foreboding spell. And in subtly clarifying what Waters left deliberately ambiguous, it identifies a hostile spirit that can’t so easily be exorcised: curdled emotions going bump in the dark.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.

Keep scrolling for more great stories.