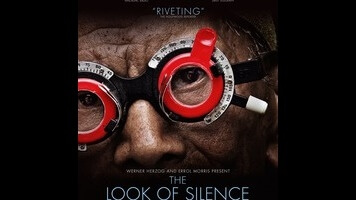

“Anonymous” is a word that pops up numerous times during the end credits of Joshua Oppenheimer’s courageous new documentary, The Look Of Silence. It appears in lieu of actual names, allowing members of the crew—five assistant directors, several drivers, a gaffer—to conceal their involvement in the movie. Safety precautions must be taken, after all, when you’re participating in an act of defiance as daring as the one Oppenheimer performs here. Directly confronting the perpetrators of the 1965 Indonesian genocide, many of who still hold prominent positions of power in the country they ravaged, The Look Of Silence fearlessly pokes at the consciences of ruthless, unrepentant war criminals. For the local artisans who accompanied Oppenheimer, a native of Texas, on his village-by-village inquisition, filmmaking was a life-and-limb risk. “Anonymous” is their shield, but it’s also their badge of solidarity—a reminder of the silent majority for which the movie speaks.

Oppenheimer has tackled this topic before, albeit in a less accusatory manner: The Act Of Killing, his last film, approached the genocide—a wave of carnage that claimed the lives of roughly a half-million people, all condemned under the blanket label of “communist”—through the eyes, anecdotes, and amateur cinematic reenactments of the murderers themselves. For all the acclaim that movie earned, there were plenty repelled by its methods. Was Oppenheimer simply enabling these remorseless killers by handing them the means to glorify their atrocities on camera? Did he provoke their sense of moral responsibility, as intended, or simply feed their delusions of grandeur? The Look Of Silence isn’t as conceptually daring as its predecessor—it lacks the queasy meta framework of Killing—but it’s absolutely vital as a companion piece, one that provides the survivors of the genocide their own voice. The two films, it’s now clear, are equal parts of a single damning whole.

Most of Silence revolves around Adi, an optometrist, gaining access to the perpetrators, usually under the guise of an eye exam, and grilling them with blunt questions about their involvement in the genocide, often going as far as demanding on the spot that they take personal responsibility. What none of the men know, but quickly find out, is that Adi’s older brother, Ramli, was one of the countless innocents brutally slaughtered during their campaign of terror. The tragedy nearly destroyed his parents; his mother—who spends most of her days caring for her elderly and increasingly senile husband—is open about the ways she tried to mold the son she gave birth to afterwards into the one she lost. The family learned the horrific details of Ramli’s death through interview footage Oppenheimer shot for The Act Of Killing. Here, the director includes a few blatantly manufactured shots of Adi watching that footage, the imagery clearly composited onto a blank television screen. It’s the type of permissible bend in documentary ethics that the film’s executive producers, Werner Herzog and Errol Morris, might perform in search of an “essential truth.”

It’s also not the only ethical breach one could possibly detect in The Look Of Silence. In one sense, Oppenheimer’s sneak-attack methods aren’t so different than the ambush filmmaking practiced by Michael Moore, albeit with much more artfulness and at much greater risk. But do the rules of journalistic engagement really apply to men who have bragged about their genocidal actions for half a century? The lionized thugs Oppenheimer films in Silence are technically less powerful than the “stars” of The Act Of Killing—they’re regional leaders, not national politicians like Anwar Congo—but they’re no less ghoulish in their nostalgic pride, cackling about chopping up bodies and drinking human blood. That’s why there’s such a cathartic charge to seeing them challenged at point-blank range by Adi, who has the steel nerves and stormy calm of someone who’s decided that keeping quiet is no longer an acceptable response to the crimes committed against his family and homeland. Publically celebrated as heroes, these aged, untouchable gangsters are forced, for possibly the first time ever, to answer for what they’ve done. They respond with predictable antagonism—deflecting blame, accusing Adi of “talking politics,” making veiled death threats—but the sound of an unspoken rule being violated is deafening.

“Do you want revenge?” someone asks Adi late into the movie. While the doctor insists that’s not what he’s after, there’s a distinctly vengeful slant to some of his crusade, particularly the moment where he confronts the surviving family members of a dead perpetrator—a man who celebrated Ramli’s murder in ghastly picture-book form—with the horrible knowledge of what their father and husband did in ’65. Whether this is fair play or not is a tricky question. What matters is that Adi’s campaign of open discussion, his determination to address the elephant in every room, ultimately scans as a good-faith attempt at building a new Indonesia—a country ready, ideally, to address and atone for its past mistakes. It may be too late to coax a confession of culpability—a moral awakening, really—out of the human monsters the film puts on trial. But for Indonesia’s younger citizens, like the gangster’s daughter who apologizes on behalf of her unapologetic father, reconciliation seems possible. The Look Of Silence is a powerful gesture of political rebellion, one whose boldest action isn’t damning mass murderers to their faces, but being willing to believe that their stranglehold on country and history could be broken.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.