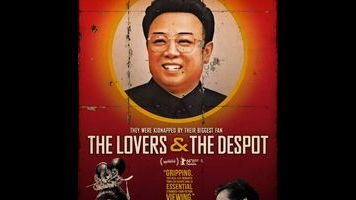

Contemporary filmmakers like Bong Joon-ho, Park Chan-wook, and Kim Ki-duk have landed South Korean movies in U.S. arthouses, but their success hasn’t yet led to much interest in the country’s rich cinematic history. One of the most overlooked figures in the West is Shin Sang-ok, a prolific director whose regular collaboration with his wife, actress Choi Eun-hee, produced at least one masterpiece: 1961’s romantic weepie The Houseguest And My Mother (sometimes called My Mother’s Tenant). Shin’s films are extremely difficult to see in the States, and one can only hope that The Lovers And The Despot, a new documentary about Shin and Choi, will help to change that. Unfortunately, this bland, incurious oral history focuses exclusively on what’s admittedly the most superficially fascinating chapter of their lives: the eight years they spent making movies together in North Korea, after Kim Jong-il had them kidnapped.

Granted, that’s pretty insane. The Lovers And The Despot may be worth seeing just to hear audio recordings surreptitiously made by Choi, in which the late dictator angrily rants about his country’s terrible movies. Determined to improve their quality, he asked for the name of the best director in the South; told it was Shin, he then had agents abduct Shin’s ex-wife in Hong Kong. (Shin and Choi had divorced a couple of years earlier.) When Shin went to Hong Kong looking for her, he, too, was allegedly kidnapped, though many believed—and some still believe—that he voluntarily defected. From 1978 until 1986, when they escaped, the pair were prisoners of the regime, though they spent the first half of that time separated (with Shin, due to a “misunderstanding,” being tortured in various concentration camps). Once finally reunited, they remarried and began churning out movies for the North at a ferocious pace. Choi claims that they made 17 features in roughly two years, which makes even Fassbinder look like a slacker.

What were those movies like? How did they compare to the acclaimed films Shin and Choi had previously made in South Korea? The Lovers And The Despot either doesn’t know or, worse, doesn’t care. Directors Robert Cannan and Ross Adam are interested solely in the crazy-true-story angle, but they fail to provide much more detail than does the preceding paragraph. Talking-head interviews with Choi, the couple’s children, and various other people connected with the case are strictly expository: This happened and then that happened. (Shin died in 2006. His final film, believe it or not, was 1995’s 3 Ninjas Knuckle Up.) The rest of Despot consists of clips from Shin’s oeuvre juxtaposed with what appear to be newly shot reenactments designed to look like clips from Shin’s oeuvre, plus some actual archival footage—none of it identified in any way. This might have worked for a filmmaker as well known as Spielberg or Scorsese, as viewers could reasonably be expected to recognize actors and famous moments. Here, it reduces the entire career of a great director to mere illustration, offering no insight about the events being illustrated. That time would be better spent reading Shin’s Wikipedia page and tracking down My Mother’s Tenant.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.