The manipulative Cannes award-winner Capernaum pleads for your pity at every turn

Of all the emotions that movies can inspire and provoke, the cheapest by far is pity. Any non-sociopathic human instinctively feels protective toward suffering innocents, particularly children; it requires little skill to manufacture sympathy (rather than empathy) by putting a blameless character through some fictional wringer. Easier still if we know or sense that the hellscape in question reflects actual events. Great films—think of Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D., or the finest work of the Dardenne brothers—strive to complicate these knee-jerk responses, often in ways that make us a mite uncomfortable. Mediocre films lean on them, hard.

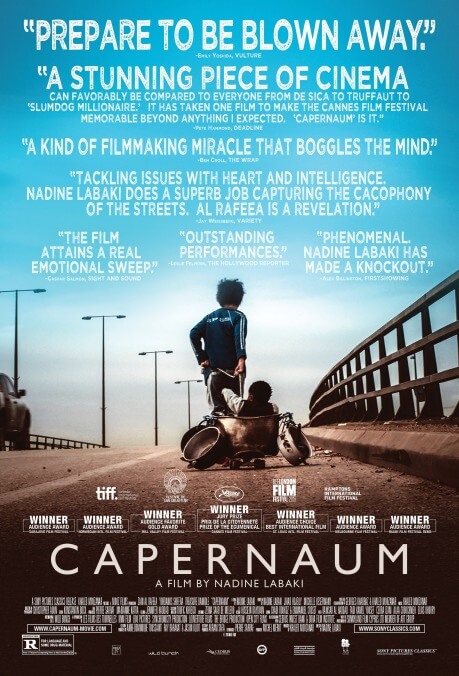

Despite having won the Jury Prize (basically third place) at Cannes this year, Capernaum, the latest effort from Lebanon’s Nadine Labaki (Caramel, Where Do We Go Now?), falls squarely into the latter category. It’s the story of a little boy whose existence is so relentlessly miserable that he’s actually suing his parents for having given birth to him—a conceit so ludicrous that it could only be successfully played for comedy, but which Capernaum treats with righteous fury. The film opens at the trial, where Zain (Zain Al Rafeea, a Syrian refugee in real life), who’s roughly 12 or 13, sits glowering at everyone in view while his attorney (played by Labaki herself) argues that he shouldn’t be held accountable for a crime he’s committed, essentially being Not Guilty By Reason Of Adversity. The very nature of this proceeding is unclear—it seems to be simultaneously criminal and civil, with Zain at once defendant and plaintiff—but that’s of little importance, since it turns out to be a framing story designed to trigger a whole lot of upsetting flashbacks.

“And you, Capernaum, will you be exalted to heaven?” Jesus rhetorically asks in Matthew 11:23. “No, you will brought down to Hades.” Hence, presumably, the movie’s title (never referenced on screen), since Zain goes through hell on Earth. After watching his parents sell his little sister to a leering middle-aged man, he runs away from home—always a harrowing experience, made even worse in this case by the fact that Zain lacks an ID card that would potentially entitle him to public assistance, as his parents couldn’t afford the fee. Taking refuge at an amusement park, he meets an Ethopian woman, Rahil (Yordanos Shiferaw) and her infant son, Yonas (Boluwatife Treasure Bankole, actually a girl—take that, Linda Hunt!), immigrants who are in equally dire straits. It’s a promising narrative development, until Rahil, who’s negotiating to purchase fake papers from a clearly shady dude, suddenly disappears. So now Zain isn’t just an ill-treated child living on the street—he’s also responsible for keeping a 1-year-old from starving to death. As with Dickens’ Little Nell (per Oscar Wilde), one must have a heart of stone not to laugh.

There’s no doubt of Labaki’s good intentions, and it’s easy to imagine how moved she must have been by the stories of her non-professional actors, many of whom reportedly endured hardships similar to those of their characters. Capernaum brims with compassion for the downtrodden, and that will likely be enough for many viewers (as it clearly was for the Cannes jury). But the film amounts to a series of easy emotional lay-ups, devoid of any psychological nuance or challenging inflection. And whenever it does briefly flirt with becoming something more than a guided tour of hopelessness, Labaki cuts back to the trial, reminding us that our ultimate destination is a kid’s stated desire to be retroactively nonexistent. That’s heartbreaking, but the challenge for artists is to achieve that using a scalpel, not a sledgehammer.