Of course, demeaning oneself to find or keep a job isn’t an exclusively male province (as the Dardenne brothers’ magnificent Two Days, One Night, starring Marion Cotillard, demonstrated a couple of years ago). The Measure Of A Man’s French title has nothing to do with gender, in fact—the film was originally called La Loi Du Marché, which translates as The Law Of The Market. None too forgiving, that law. After being laid off from the factory where he’d toiled for decades, Thierry spent more than a year completing a training course that doesn’t actually qualify him for anything, and he’s perceived as both too old and too financially needy for the sort of entry-level positions that are available to him. He finally manages to get hired as a security guard for a gigantic department store, but the victory is decidedly pyrrhic, as he now spends 40 hours per week busting people who are every bit as desperate and mortified as he had been prior to donning his uniform. Standing in the store’s back room, watching the interrogation of fellow employees who he’s caught tapping the till, he looks even more uncomfortable than he did waiting for that Skype interview call.

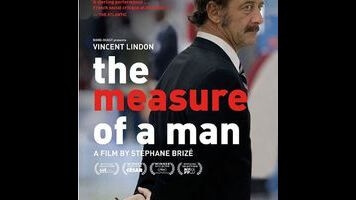

Brizé doesn’t have the Dardennes’ gift for narrative complexity, and he stacks the deck against his hero more than is really necessary, in both halves of the film (which is neatly bisected, Before Job and After Job). Thierry’s son (Matthieu Schaller) has what appears to be cerebral palsy and requires expensive care, and one of the distraught shoplifters Thierry apprehends subsequently commits suicide, which really feels like overkill. But The Measure Of A Man’s beating heart is Lindon’s performance, for which he deservedly won Best Actor at Cannes last year (and, earlier this year, the César in the same category). Lindon pulls off something similar to what Imelda Staunton so memorably accomplished in Mike Leigh’s Vera Drake: After spending the first half of the film in constant motion, Thierry almost completely shuts down for its second half, scarcely uttering a word after being hired. His growing distaste at serving as a representation of The Man has to be read on his face, which Lindon somehow manages to keep placid while still registering the necessary emotion. Watching this passionate scrapper die inside after finally achieving his hard-fought goal is heartbreaking. For what shall it profit a man if he shall gain the minimum wage, and lose his own soul?

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.