The Method tells the story of the 20th century’s most controversial acting practice

Isaac Butler's history chronicles the infamous Method style of acting—from Stanislavski to the devotees who dominated the screen throughout the mid-20th century

If you read the widely shared New Yorker profile of Jeremy Strong published this December, you may have guffawed—along with most of Twitter—at the extremes the Succession actor puts himself through to transform into the character he plays, Kendall Roy. True to Kendall’s black sheep persona, Strong self-isolates from his castmates. He borrows items from the wardrobe department to inspire after-hours motivation, and wears his shoelaces tied foot-crushingly tight, just like one of Rupert Murdoch’s media scion sons. When Kendall frequently falls off the wagon, Strong, too, arrives on set tipsy but ready to work.

On the set of The Trial Of The Chicago 7, Strong, playing the anything-for-attention activist Jerry Rubin, begged to be sprayed with real tear gas while filming a reenacted riot. His director declined. American cinephiles characterize Strong as a Method actor, a capital “A” artist who fully immerses themselves in a role to obtain, and thus perform, an authentic, psychological, and emotional capital “T” truth.

That self-serious dedication to stagecraft was dreamed up nearly a century and a half ago by Konstantin Stanislavski, an amateur Russian actor who would make Jeremy Strong proud (Strong, it bears mentioning, eschews the Method label for what he calls “identity diffusion”). Thinking the state of late-19th-century Russian drama stale, Stanislavski prepared for the role of the titular Miserly Knight in a production of Alexander Pushkin’s opera with complete and, some might say, crazed commitment, locking himself in a rat-infested castle cellar, where he eventually conjured up the will to play the part as he wanted, as well as a miserable cold.

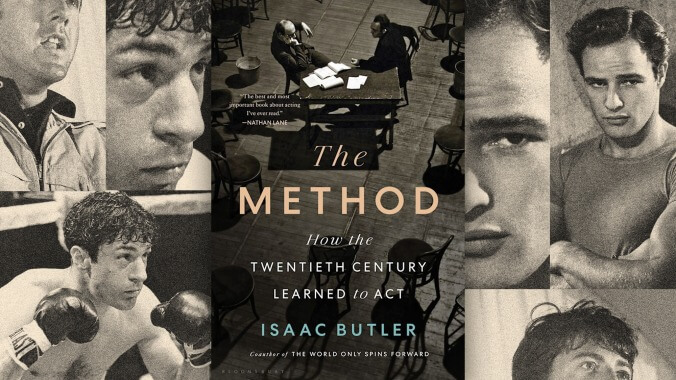

Stanislavski’s story is expertly and exactingly told in Isaac Butler’s The Method: How The Twentieth Century Learned To Act, a cultural history of the Russian acting master, the many teachers who proselytized his message, and the Method-seeking actor acolytes—Brando, Hoffman, Pacino, and De Niro, among them—who dominated the stage and screen throughout the mid-20th century.

Before the acting ethos that became known as the Method, there was perezhivanie, Stanislavski’s term for experiencing or embodying a fictional role and the actual self simultaneously. Perezhivanie relied on unconventional line readings, irregular pauses, and what Butler calls an “accumulation of everyday microdramas”—a prepared cough or sniffle, a piece of paper purposefully fumbled—to make the audience feel as if they were witnessing reality.

Stanislavski saw a “sacred task” in perezhivanie, a way for actors to “bear witness to purity and truth.” Actors flocked to his revolutionary Moscow Art Theatre, founded the same year, 1898, as the Russian Social-Democratic Workers Party, forerunner to the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

Unhappy with the limits of perezhivanie, Stanislavski piled theory upon theory, creating a dizzying acting lexicon—the creative mood, the superconscious, affective memory, motivation, ya yesm, the Magic If—eventually subsumed under a system he simply called the “system,” written in quotes and lowercase to emphasize its constantly evolving nature. He forced his actors to live communally, to do monotonous table reads (see the recent film Drive My Car), and soul-crushingly repetitive rehearsals. “I performed all sorts of experiments with [the actors],” he admitted in his autobiography. “I tortured them.”

War and revolution scattered the MAT troupe to Europe and, more importantly, the United States, where the Polish theater director and “system” advocate Richard Boleslavsky found an audience of actors hungry for Stanislavski-derived lectures and what he called “acting laboratories.” Auditions often hinged on the bizarre. One student, Lee Strasberg, was required to recite a Shakespeare monologue of his choosing before crossing the audition room while pretending the floor crawled with poisonous snakes.

Strasberg became America’s star pupil of the “system,” eventually adopting and Americanizing Stanislavski’s methods into a practice he called the Method. In 1931, Strasberg co-founded, along with directors Harold Clurman and Cheryl Crawford, the Group Theatre, an arts collective that enjoyed early but brief successes, and is most notable today for launching the careers of playwright Clifford Odets and director Elia Kazan, who would go on to define stagecraft and cinema in the 1940s and ’50s.

The Group Theatre succumbed to schisms by decade’s end, and Butler clearly parses the murky divisions that continue to define the Method, then and today. Strasberg’s improvisational and emotional recall is exemplified by Dustin Hoffman, who conjured his embarrassing teenage sexual encounters to play the awkwardly horny Benjamin Braddock in The Graduate. Strasberg’s chief rival, Stella Adler, preached reliance on imagination and external research and transformation. Picture Marlon Brando’s blustery swagger in A Streetcar Named Desire or Robert De Niro’s extreme bodily metamorphosis in Raging Bull (the actor gained so much weight to play the late-career boxer Jake LaMotta that he struggled to tie his shoelaces). The third Method teacher of note, Sanford Meisner, instructed his students to not focus on themselves but to simply exist on stage, in a practice he called “living truthfully under imaginary circumstances.”

By the 1970s, Method actors were racking up both Academy Awards and detractors. Wannabe Brandos were being taught by the “friend of a friend of a former student of someone who was thrown out of an early 1930 class given in the summer by [some long-forgotten Russian master]” one critic scoffed. When Hoffman explained the lengths to which he put himself to portray a runner on the run in Marathon Man, his costar, Laurence Olivier, asked, “My dear boy, why don’t you try acting?”

By the late 1970s, the original teacher-trailblazers began dying just as the Hollywood blockbuster came to dominate box offices. There was no need to act Method while aboard the Orca or Death Star. A new wave of actors, some who just came to act, found the Method’s masochistic and brimming with machismo. Meryl Streep dismissed the technique as “a lot of bullshit.”

Yet, the Method is “still taught, and misunderstood, and championed, and maligned,” Butler writes. Moviegoers might not know how to pronounce perezhivanie but they know it when they see it on screen. This book will deepen your understanding of how and why we watch cinema. No tear gas needed.