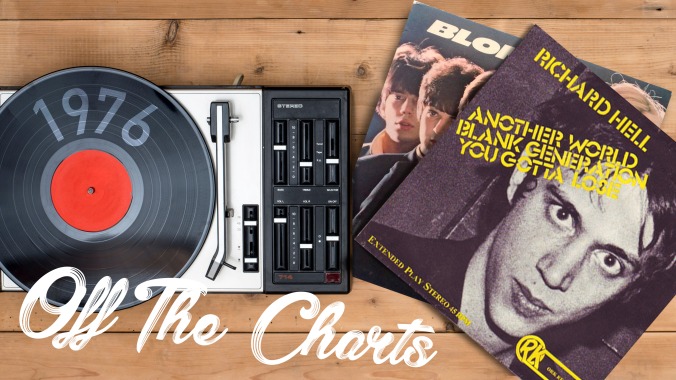

The Modern Lovers, Pere Ubu, and Blondie were ready to rip up 1976

Image: Graphic: Nicole Antonuccio

The year: 1976

Billboard Hot 100’s Top 20 Songs Of 1976

1. Wings, “Silly Love Songs”

2. Elton John & Kiki Dee, “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart”

3. Johnnie Taylor, “Disco Lady”

4. The Four Seasons, “December, 1963 (Oh, What A Night)”

5. Wild Cherry, “Play That Funky Music”

6. The Manhattans, “Kiss And Say Goodbye”

7. The Miracles, “Love Machine”

8. Paul Simon, “50 Ways To Leave Your Lover”

9. Gary Wright, “Love Is Alive”

10. Walter Murphy & The Big Apple Band, “A Fifth Of Beethoven”

11. Hall & Oates, “Sara Smile”

12. Starland Vocal Band, “Afternoon Delight”

13. Barry Manilow, “I Write The Songs”

14. Silver Convention, “Fly, Robin, Fly”

15. Diana Ross, “Love Hangover”

16. Seals And Crofts, “Get Closer”

17. Andrea True Connection, “More, More, More”

18. Queen, “Bohemian Rhapsody”

19. Dorothy Moore, “Misty Blue”

20. The Sylvers, “Boogie Fever”

“You’d think that people would have had enough of silly love songs,” Paul McCartney sang in the No. 1 hit of 1976, a year when Americans most definitely had not. Indeed, the nation rang in its bicentennial by celebrating what also felt like the 200th straight year of sweet pop nothings, scooping them up like commemorative $2 bills in all their myriad forms: love machines. Love hangovers. Lovers being left in 50 ways or less. What people had had enough of, at least as far as the Billboard single charts were concerned, was rock ’n’ roll. That year, disco dominated all: “Disco Lady,” “Disco Duck,” even a disco rendition of Beethoven were all huge hits that year, their successes and the attempts to emulate them drowning everything in syrupy strings and four-on-the-floor beats, to the point where Kiss’ “Rock And Roll All Nite” felt like a genuine cry of revolution, rather than just something Paul Stanley thought sounded good.

But as always, singles only tell part of the story. In truth, rock was huge in 1976—big and bloated and browning in the Malibu sun, like the coke-dusted bellies of the Eagles as they rolled out of their beach house beds to record Hotel California, the year’s definitive statement on bored rock star excess. When people sneer about “dinosaur rock” these days, they’re usually picturing 1976, a peak AOR era when the likes of Peter Frampton, Foghat, Grand Funk Railroad, Bad Company, Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band, Thin Lizzy, Nazareth, Blue Oyster Cult, Boston, Kansas, and Styx all stomped the earth, all trying to one-up each other with laser light shows and 30-minute drum solos—all while Robert Plant rode astride a white stallion in The Song Remains The Same, the paragon knight of rock’s roundtable of wankery.

Is it any wonder, then, that 1976 was Year Zero for punk rock? All that pompous, preening nonsense finally triggered the collective gag reflex of cities from London to L.A., causing them to spew out scores of fast, loud, and snotty bands who didn’t just hate the fucking Eagles, man—they wanted to kill ’em. The year kicked off with the first issue of Punk (a cartoon Lou Reed glaring from its cover) and ended with the debut of “Anarchy In The U.K.” The months in between saw The Sex Pistols’ legendary gig at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall and the release of Live At CBGB’s, these transatlantic crucibles forming the bands that would soon dominate the underground: The Clash, Black Flag, The Buzzcocks, The Cure, Wire, The Fall, Joy Division, Siouxsie And The Banshees, The Cramps, The Jam, Generation X, Madness, The Slits, and X-Ray Spex all first got together that year.

Most significantly, April saw the release of the first album from this burgeoning new scene that would actually break into the mainstream, The Ramones’ The Ramones, a record of game-upending blitzkrieg pop that actually landed at No. 111 on the Billboard 200—a warning shot to Paul McCartney, Robert Plant, et al. that their days of preening and “silly love songs” were rapidly drawing to a close. (Although, not really… Both those guys were fine. And actually, “I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend” is a silly little love song. Still, you get the gist.)

In fact, we easily could have filled this whole list with nothing but punk rock classics—but of course, that wouldn’t tell the full story of 1976 either. The truth is, there were lots of equally important, equally overlooked records that year from the realms of tropicalia, reggae, krautrock, folk, country, funk, and beyond. If you actually have had enough of silly love songs, give some of these a shot.

Kate & Anna McGarrigle, “Heart Like A Wheel” (January 1976)

“Heart Like A Wheel” is the first song Anna McGarrigle ever wrote, and two years before she and sister Kate released it on their debut, it had already been recorded twice—most famously by Linda Ronstadt, whose cover became the title track of her 1974 breakthrough. Although the Canadian folk duo’s version failed to chart itself, it’s in their rendition where you can hear why it’s remained such a favorite for other singers in the way their ghostly, intertwining vocals give it a timeless quality—as though composed by a lovestruck minstrel on a lute. It’s a universal ode to the kind of love that can sink you (“It’s only love / That can wreck a human being and turn him inside out”), and one was that given even greater personal meaning in ’76, when Kate McGarrigle was nearing a divorce from fellow songwriter Loudon Wainwright III. The song and album kicked off a long and esteemed career for the sisters, who went on to see “Heart Like A Wheel” covered many times by everyone from Billy Bragg to The Corrs to Kate’s own children, Martha and Rufus Wainwright. [Gwen Ihnat]

Pere Ubu, “Final Solution” (March 1976)

At the time Pere Ubu’s second single was released, there weren’t really any groups like it—and still aren’t. The frantic, funny, paranoiac, self-proclaimed “avant-garage” band was far wilder and weirder than the Cleveland unit it splintered from, Rocket From The Tombs (half of which went on to form The Dead Boys), smashing up blues riffs, Beefheart provocation, and MC5 attitude with analogue synth squalls and the hieroglyphic fragments of singer David Thomas’ singular mind. That uneasy formula fully coalesced on 1976’s “Final Solution,” one of the final recordings to feature foundational guitarist (and local legend) Peter Laughner. An angst-ridden, absurdist howl from the twin abysses of adolescence and the industrial Midwest, it tells a common tale of teen alienation: Its narrator is a pock-marked mess, ignored by girls and kicked out by his mom, who seeks his catharsis in music. But it goes to unusual extremes with its refrain of “Don’t need a cure / Need a final solution.” (Thomas has insisted the song was a reference to Sherlock Holmes, not the Holocaust, though the band still dropped it from its repertoire after the punks started flirting with Nazism.) “Final Solution” remains an unnervingly gritty, galvanizing listen, with Thomas’ hollow-eyed snarls penned in by synthesizer squiggles and sudden blares of distortion, before Laughner’s guitar lifts him up via a surprisingly poignant solo. [Sean O’Neal]

Debris’, “One-Way Spit” (April 1976)

Debris’ was at least two years too early and about 1,400 miles too far to be part of the New York no-wave scene that would have made them icons, destined to be mentioned in the same breath as Richard Hell, James Chance And The Contortions, and the like. Instead, the band appeared like a mutant cow in the flat farmlands of Chickasha, Oklahoma, where its redneck-baiting members put their love of The Stooges, The Velvet Underground, and Captain Beefheart into a skronking, thrashing pile-up of arch, arty nastiness that did little more than baffle and piss off the locals during Debris’ incredibly short run. But thanks to a bargain deal of studio time with a 1,000-record pressing thrown in, the band managed to create Static Disposal in just “six hours and 59 minutes,” according to the liner notes, bashing out what’s now considered a lost punk classic—though it wasn’t until after the band had already broken up that anyone caught on. Album opener “One-Way Spit” must have sounded like a tractor crash to the Chickasha press: It begins with singer/shouter Chuck Ivey practically throwing up on the mic before he counts off a dizzying cacophony of synth squiggles, saxophone bleats, and mangled guitar under Ivey’s yelps and howls. Today it sounds like a testament to the power of punk to sow rebellion even in the most barren of fields. Back then it was enough to get Debris’ an invite to CBGB’s after it had already disbanded, a long way away from its true home. [Sean O’Neal]

Death, “Politicians In My Eyes” (May 1976)

The brothers Hackney—David, Bobby, Dannis—started out in a group called Rock Fire Funk Express before changing its name to Death on David’s insistence, something that went over about as well in its local scene as the sight of three young black Jehovah’s Witnesses playing righteously pissed protopunk in 1970s inner-city Detroit. While Death was unique and clearly talented enough to earn the backing of Clive Davis, who paid for its earliest studio sessions, that moniker cast a pall no one could get past. And after the Hackneys refused to change it, Davis pulled his support, forcing Death to self-release its 1974-recorded debut single, “Politicians In My Eyes,” in a run of just 500 copies. It would be nice to say that the Hackneys were proven right—that music this raw and incendiary simply bent the world to Death’s stubborn will. But it would take another three decades before everyone finally caught up, long after the band’s 1977 breakup and the loss of David Hackney to cancer in 2000. While “Politicians In My Eyes” wasn’t appreciated in its time, it stands now as a classic of the era, a timeless, fight-the-power anthem that combines MC5 fury and big Hendrix guitar sounds into something that sounds perpetually of the moment, even if the band had to wait years for its own. [Sean O’Neal]

Junior Murvin, “Police & Thieves” (May 1976)

Junior Murvin lent his feathery falsetto to various bands and labels throughout Jamaica before finally getting an audition with dub legend Lee “Scratch” Perry, for whom he performed the song that’d go onto be his defining work, “Police & Thieves.” They recorded the track that same day with The Upsetters as the backing band, with hallucinatory guitars that seem to phase in and out of reality alongside Murvin’s alternately haunting and optimistic melodies. This duality can be felt in the lyrics, too, which detail street-level resistance against a timeline encompassing “genesis to revelation.” The track made its way throughout Jamaica and England, where some punks called The Clash decided to cover it for their self-titled debut. Still, Joe Strummer’s rough bark is about as far as possible from Murvin’s original performance, which is almost angelic in its lightness. [Clayton Purdom]

Blondie, “X Offender” (June 1976)

“X Offender” was meant to introduce Blondie to the world, though its debut single (and opening track from its first, self-titled album) only became a success thanks to its B-side, after an Australian TV station played the more Phil Spector-ish pop song “In The Flesh” instead. You can see why some might have balked at “X Offender.” Bassist Gary Valentine wrote the song—originally titled “Sex Offender,” before the label intervened—about an 18-year-old arrested for having sex with his underage girlfriend. Then Debbie Harry changed the lyrics to make it a love story about a prostitute who falls for the cop who busts her. Either way, it’s touchy subject matter, especially for a debut. But “X Offender” still functions as a perfect salvo for the band, sounding both nostalgic (with its surf guitar and a spoken-word intro worthy of The Ronettes) and ahead of its time (layered with the kind of sweet-sounding synths that would come to define candy-coated ’80s new wave). Giving voice to the song’s narrator, Harry sounds smitten, menacing, and fully in control of the situation (“I think all the time how I’m going to perpetrate love with you / And when I get out, there’s no doubt I’ll be sex offensive to you”), her regal, commanding rock persona already fully formed. [Gwen Ihnat]

The Modern Lovers, “Roadrunner” (August 1976)

Jonathan Richman’s ode to the simple joys of barreling down the Massachusetts Turnpike late at night, radio blaring while you get your modest suburban kicks, had been around since at least 1970, when Richman was still in the teen years that inspired it. In fact, there are several recorded versions of “Roadrunner” dating back to 1972, including a 1974 solo rendition (backed by The Greg Kihn Band) that became a minor U.K. hit, its Velvet Underground-nicking, proto-punk churn quickly inspiring covers from artists like Wire and The Sex Pistols as they oriented their nascent sound around it. But the “Roadrunner” everyone knows—the one that would become a standard worthy of politicians proposing it become Massachusetts’ official rock song—was first released in 1976, on The Modern Lovers’ self-titled, John Cale-produced debut, arriving two years after the original band had already split up. While Richman had already disowned it, that year releasing what he regarded as his true debut, Jonathan Richman & The Modern Lovers—with all due respect to Richman—the latter is nothing compared to the record that kicks off with this seminal track. It’s the sound of youth, of freedom, of rock ’n’ roll, distilled to its purest form, as sacred a text as any in modern music. [Sean O’Neal]

Bobby Bare, “Drop Kick Me Jesus” (September 1976)

Despite being nominated for a Grammy and making a minor dent in the country charts, Bobby Bare’s inspirational song is mostly remembered as a goofy novelty hit. But there’s a memorable melody at the heart of this Southern-fried waltz. Written by country music stalwart Paul Craft, “Drop Kick” delivers football metaphor after metaphor, no matter how much of a reach—“All the departed dear loved ones of mine / Stick them up front in the offensive line”—all in service of the Almighty and a surprisingly sweet, deeply catchy tune. It makes for an amusingly awkward analogy, but it’s one squarely in line with the grand country tradition, not to mention your local pastor’s sermons. As Bare croons in solemn steadfastness, he’s got the will, Lord, if you’ve got the toe. [Alex McLevy]

The Suicide Commandos, “Emission Control” (September 1976)

One of those bands better known for whom they inspired than who they were, The Suicide Commandos planted the flag for punk in the Twin Cities. The trio would break up by 1979, but heavily influenced the likes of Hüsker Dü (whose Bob Mould took lessons from the Commandos’ Chris Osgood), The Replacements, and Soul Asylum. The band’s first single reflects the primordial punk ooze from which The Suicide Commandos emerged, with “Emission Control” recalling The New York Dolls and The Stooges. It’s heavy on attitude but not especially aggressive, owing much more to the sound of early rock ’n’ roll than the polemic punk the Commandos—and the other members of the nascent punk genre—would come to embrace. [Kyle Ryan]

Leon Ware, “Musical Massage” (September 1976)

Leon Ware was an old hand in the Motown music machine, having produced and written tracks for Michael Jackson, Minnie Riperton, and Donny Hathaway, among many others. A handful of demos he had been working on as a solo project were repurposed to form the basis of Marvin Gaye’s classic I Want You, on which Ware served as co-producer, helping lend the album its sumptuous mood and suite-like sequencing. His own Musical Massage, released the same year, serves as a companion piece to that triumph, legendarily slept-on thanks to poor label promotion but still incredibly rich with sonic detail and emotion. The record’s title track is a classic of quiet storm romance, with trilling strings and a vocal performance from Ware so breathy and immediate, you can practically feel it on your ears. [Clayton Purdom]

The Damned, “New Rose” (October 1976)

Americans like to squabble over what was the true first “punk” song, but the Brits—proper even when it comes to punk rock—all seem to agree that the first one to hit England was The Damned’s “New Rose,” which beat The Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy In The UK” to the stores by a whole month. Much like The Ramones’ “I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend” from that same year, “New Rose” has all the lyrical sentimentality of classic ’50s and ’60s rock—singer Dave Vanian even quotes The Shangri-Las in the intro—albeit played louder, faster, and much, much nastier. Written by guitarist Brian James, “New Rose” thrums on dirty, slashing guitar down-strokes and drummer Rat Scabies beating the hell out of his cymbals, all while Vanian sings about the object of his affections in generically poetic platitudes—sweet nothings he nevertheless manages to make sound raucously sleazy. “New Rose” was recorded in a single day with producer Nick Lowe and bundled off nearly as quickly by Stiff Records, a real straight-razor of a tune that immediately cut through everything around it. [Sean O’Neal]

Richard Hell, “Blank Generation” (November 1976)

By 1976, Richard Hell was already the lynchpin stabbed through the tattered rags of punk before the genre barely had a name. He’d already served in seminal groups The Neon Boys, The Heartbreakers, and Television. He’d popularized the spiked hair and torn clothing aesthetic that would be soon copied by The Sex Pistols (and a million more). And that year he formed Richard Hell And The Voidoids, which wasted no time in releasing its debut (under just Hell’s name), the Another World EP, on foundational punk label Ork Records. Hell had been performing its standout track, “Blank Generation,” in his other groups for at least a year, and it shows: Although the 1976 version is slower than the one that would break wide on The Voidoids’ self-titled, Sire debut the next year, there’s nothing hesitant about Hell’s performance—a sneering, yelping, nihilist cry in which Hell expounds on the existential freedom of being born into an indifferent world. “Blank Generation” became an underground hit and instant rallying cry for an entire movement, lending its title to a 1976 documentary on New York’s burgeoning punk scene (not to be confused with the rambling, faux-Godardian romance starring Hell released in 1980), and laying the blueprint for countless punk acts and proud misfits to follow. [Sean O’Neal]

La Düsseldorf, “Silver Cloud” (November 1976)

David Bowie once called La Düsseldorf “the soundtrack of the ’80s,” and while Bowie was given to hyperbole (he once compared Scarlett Johansson’s album to Tom Waits, after all), there’s definitely an argument to be made. Certainly the German band, formed in the immediate wake of Neu! by krautrock pioneer Klaus Dinger, was the soundtrack to the Bowie albums that became the soundtrack the ’80s: Bowie and Brian Eno made no secret of how much influence their Berlin Trilogy drew from the motorik churn and ambient synthesizer swirls Dinger plied both here and in his more rocking half of Neu!’s final album, Neu! ’75. You can hear that gray, glacial cool taking early shape on “Silver Cloud,” the band’s debut single, which patiently unfolds alternately humming and soaring synth sounds over eight minutes of head-nodding rhythm and distorted guitar churn. The song became a No. 2 single in Germany, a rarity for an instrumental, making La Düsseldorf an immediate sensation in its homeland. But it would take many years—and many second- and third-hand variations—before its impact would be recognized elsewhere. [Sean O’Neal]

Sex Pistols, “Anarchy In The U.K.” (November 1976)

Many months before the debut of “Anarchy In The U.K.,” the Sex Pistols’ first-ever single, the group was already notorious. “We’re not into music. We’re into chaos,” is how Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones described it to NME, and while that was certainly true of the group’s raw, violent live shows—which famously inspired young audience members to go out and form their own punk bands—there was still immediate, obvious power in the songs themselves. “Anarchy,” which hit No. 38 on the U.K. charts, served as the entire world’s rude awakening to that power: Backed by the distorted cacophony of Paul Cook’s drumming and Jones’ guitar, frontman Johnny Rotten’s bitterly sarcastic lyrics and snarling delivery embodied the rage, frustration, and hunger for revolution within the working class. It was delivered with such conviction that The Pistols were regarded as a genuine threat to the social order, something nearly every punk song that followed has aspired to. [Kelsey J. Waite]

Crime, “Hot Wire My Heart” (December 1976)

Generally recognized as the first punk single to wing its way out of the West Coast, Crime’s “Hot Wire My Heart” didn’t do much to impress contemporary critics, who sneered at the San Francisco band’s primal, thudding, and—above all—really fucking loud take on stripped-down rock. But it eventually found its way into the hands of the right people: Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore was among the few who picked up the original 7-inch, later reintroducing “Hot Wire My Heart” to a far wider audience by covering it on 1987’s Sister, then penning the liner notes for its 1991 reissue. It was there that Moore credited Crime as one of the criminally overlooked progenitors of the West Coast hardcore scene that was soon to explode, and you can hear some of those basic building blocks in Hank Rank’s tom-tom-pummeling caveman beat, and especially in the sludgy cacophony of Johnny Strike and Frankie Fix’s fist-fighting guitars. [Sean O’Neal]

Cloud One, “Atmosphere Strut” (1976)

Patrick Adams is a name that deserves recognition as one of music’s all-time greatest producers. His 30-year career saw him arranging, producing, and/or engineering hundreds of records across multiple genres—’70s soul, disco, hip-hop, ’90s R&B—and often at the forefront of their emergence. But it was his disco work in the ’70s and ’80s that made him a cult icon among DJs and dance musicians for decades to come. In addition to orchestrating more traditional club hits, Adams had a penchant for exploring the strange, cosmic edges of dance music, wrapping grooves around synthesizers—largely because he wasn’t confident in his own singing voice. That phase began with “Atmosphere Strut,” recorded under his Cloud One pseudonym. The inaugural 12-inch for P&P Records, it’s a paragon of the style Adams dubbed “underground disco.” It’s spacier, sure, driven entirely by a MiniMoog cranked into a sci-fi buzz. But it’s also grittier and tighter than the over-polished, overwrought image usually associated with the genre, resulting in a clarity that sounds like a shockingly early bridge to modern house and dance music. [Matt Gerardi]

Weldon Irvine, “I Love You” (1976)

Poet and playwright, lyricist and composer, jazz innovator and rapper—Weldon Irvine did it all. His career is bookended with fascinating collaborations. In the beginning, he worked with Nina Simone as a bandleader and wrote the lyrics to Simone’s civil rights anthem, “To Be Young, Gifted And Black.” Decades later he relocated to Queens, where he adopted the hip-hop persona of Master Wel and served as a mentor for artists like Q-Tip and Mos Def, even giving them piano lessons. On the several albums he released under his own name, Irvine primarily worked in a daring form of jazz that channeled his politics, though he also dabbled with soul—an interest that came to a head on 1976’s Sinbad. “I Love You” is a standout from that album, a silky-smooth original in the vein of Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder. The lyrics were written not by Irvine but pianist Don Blackman, and while it lacks Irvine’s headier themes, it makes up for it with picture-perfect pop arrangement. The choruses, in particular, are just so rich: the falsetto “oohs,” the ascending piano chords between each vocal phrase, and the slides leading us back into the steamy verses. [Matt Gerardi]

Jorge Ben Jor, “Ponta De Lança Africano (Umbabarauma)” (1976)

Jorge Ben Jor—or just Jorge Ben, as he was known at the time—emerged from the late ’60s Tropicalia movement as one of its most successful singers and songwriters. After a legendary string of lush, psychedelic albums that were still dominated by their Brazilian roots, Ben looked to African rhythms and the grooves of American funk to find the sound for one of his most popular LPs, 1976’s África Brasil. The result is a mesmerizing fusion of samba and funk that could easily stand alongside anything coming out of the states. Its opener, “Ponta De Lança Africano (Umbabarauma),” has also become its most famous track thanks to a legacy of covers, compilation appearances, and its status as one of the most beloved songs about fútbol ever recorded. Ben’s spare, poetic story of an African striker whose play brings his home city together is matched by raw, driving funk guitars and electrifying call-and-response sequences that evoke both African music and soccer chants. You couldn’t find a more appropriate way to symbolize the musical union Ben was pursuing. [Matt Gerardi]

The Wild Tchoupitoulas, “Brother John” (1976)

The Wild Tchoupitoulas were a New Orleans Mardi Gras Indian tribe led by George Landry, a.k.a. Big Chief Jolly. They made just one album, their 1976 self-titled debut, but it so captured the unique confluence of talent and styles in the region’s rich musical landscape—R&B, gospel, funk, zydeco—that it became a near-instant classic. Sure enough, you can hear the very spirit of New Orleans in the lazy funk rhythms and soulful call-and-response chants of “Brother John.” The album’s credits read like a who’s who of New Orleans music, too, with Allen Toussaint behind the boards, The Meters backing the tribe, and Big Chief’s nephews Charles and Cyril Neville in the rhythm section. Charles and Cyril in turn drafted their brothers Art and Aaron to sing, unwittingly founding the Neville Brothers right there in the studio. (That’s the unmistakable sound of young Aaron kicking things off with a variation of the Indian chant “Jock-A-Mo” at the start.) [Kelsey J. Waite]

Tom Zé, “Dói” (Unknown 1976)

One of the originators of Brazil’s psychedelic tropicália sound, Tom Zé traded pop and folk for more a experimental direction over the course of the 1970s, without ever losing his sense of humor. “Dói” (“It Hurts”), which kicks off the second side of his eclectic concept album Estudando O Samba, is a buoyant song of regret and heartache; somewhere in the contradiction between Zé’s sorrowful voice and the transcendent rhythms and backing vocals is the essence of this quirky, unconventional genius’s tragicomic worldview. A failure upon its original release, Estudando O Samba played a pivotal role in resurrecting Zé’s career in the early 1990s, thanks to efforts of super-fan David Byrne. [Ignatiy Vishnevetsky]

RECOMMENDED FURTHER LISTENING

Claudja Barry, “Love For The Sake Of Love”

The Bizarros, “Lady Doubonette”

The Chosen Few Band, “What It Takes To Live”

Cluster, “Sowiesoso”

Eddie And The Hot Rods, “Teenage Depression”

Fela Kuti, “Zombie”

Lee Scratch Perry, “Zion’s Blood”

The Nerves, “Hanging On The Telephone”

Nervous Eaters, “Loretta”

The Saints, “I’m Stranded”