The must-read Djeliya is a sublime West African fantasy epic

Juni Ba's masterful graphic novel combines multicultural influences with traditional storytelling, to thrilling results

Djeliya hits all the right notes for larger-than-life storytelling. It’s the epic fantasy tale of Awa, a West African orator, historian, and praise singer (also called a jeli), and Mansour, the young dethroned prince she serves. Souamoro, an old and evil wizard king, has broken the world and disappeared. Awa and Mansour must journey across a futuristic wasteland to Souamoro’s tower. From this classically structured premise, Djeliya showcases the unique way that cartoonist Juni Ba’s influences—Franco-Belgian bandes dessinées, manga and anime, American comics and cartoons, West African folklore, the Epic of Sundiata, and the jeli tradition—coalesce into an accessible yet sublime narrative.

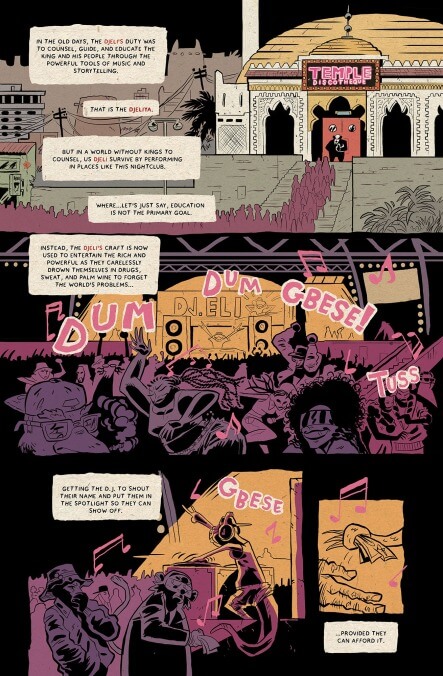

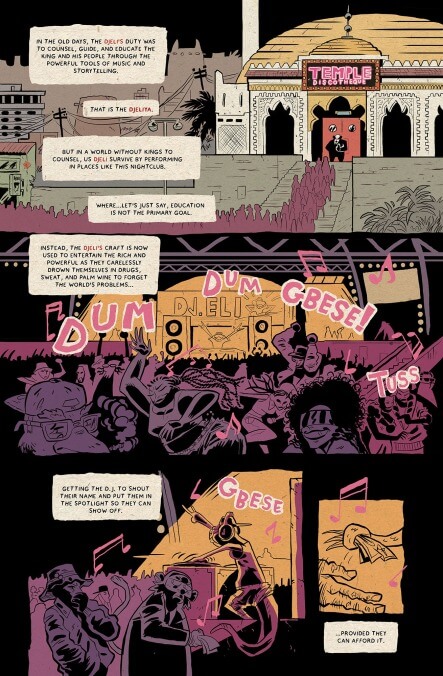

The book itself is as multifaceted as its influences, containing various narratives and themes that Djeliya, through its rhythm, expertly balances. That this work is so harmoniously crafted is fitting, as Ba’s grand achievement is replicating the narrative musicality of the jeli—who balance praise-singing, genealogy, and history with musical accompaniment—on the two-dimensional page. At the most obvious level, Djeliya’s pages take great care in representing the sound of music visually: There is frequent onomatopoeia and musical notes occasionally act as a reading guide for the reader.

On a deeper level, Ba transposes almost the entire jeli tradition onto the page. Each of the three aforementioned narrative modes of the jeli are featured, either through Awa’s various tales (as is most frequent), the mouth of a side character, or an informal non-diegetic narrator. And just as the various modes of the jeli are aurally distinct, the different narrative modes in Djeliya are presented with different art styles. The main narrative features art most heavily reminiscent of Samurai Jack, but other styles, often evoking African comics like Cauphy Gombo, pop up too.

Djeliya is a book filled to the brim with action and influences—so much so, there’s even a bibliography for the referenced works. That the bibliography for a book published in English contains French sources on African folklore and myth is testament to the multicultural nature of its author and the work itself. The book is tailored to Anglophone audiences without losing any of its Francophone flair; or, for that matter, diluting any of its other cultural influences.

In response to the longstanding debate over the degree to which writers from marginalized groups (say, a Francophone Senegalese writer in a Western industry) should reveal aspects of their culture to those outside of the marginalized group, Ba leans on the pedagogic nature of the jeli as keeper of cultural memory: The book quite literally ends on a moral. Djeliya’s ease of access for Anglophone readers of any background is a joy. Like in many language textbooks, non-English words are introduced in red first with a footnote definition but later presented in black, the expectation being that the reader is now familiar with the word. The book contains significant backmatter that, while providing a jumping-off point for potential further research, explains symbols and concepts used within the book. Even readers of similar cultural backgrounds as Ba might appreciate the book’s accessibility—it just might allow them to be surprised by how cleverly he experiments with the familiar.