The Mustang doesn’t buck indie convention—it gives it a surge of new dramatic life

A man and a horse lay sprawled on the ground. Dust swirls around them. One has a knee in his back. A tranquilizer begins to flow through the veins of the other. The perpendicular world slows and bears down at once. It’s chaos above, but there in the dirt, the man is arrested by what he sees. The moment crystallizes, and inside it, something kindles. It’s kinship, small but tenacious, fueled by something like remorse. While the guards shout above, the man feels the flickering. For that instant—and here comes a hell of a banality—he and the horse are one.

It’s a cliché so hoary, so saccharine, that to lead a review with it probably risks turning people away, though it doesn’t compare to the chance this film takes in making such a moment a piece of its emotional bedrock. Yet The Mustang shouldn’t be dismissed. The first feature directed by French actor Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre deploys every too-familiar beat with deliberation. A jocular old-timer shows a stoic newcomer how they do things ’round these parts; a glorious blue sky can be glimpsed only through through the tiny window in a dark cell; when all hope seems lost, an animal tranquilly approaches with what seems like compassion. Under de Clermont-Tonnerre’s steady gaze, and in the hands of an exceptional performer, these tropes—those of the Western, the prison drama, and countless boy-and-his-dog stories—aren’t hollow. They spring up like weeds through dead soil, and flower unexpectedly.

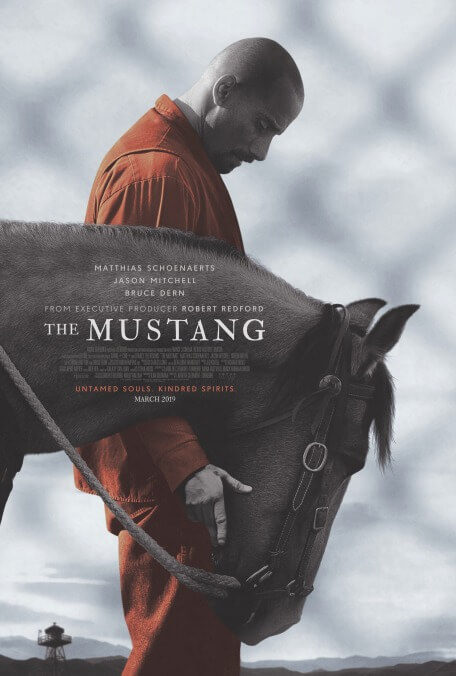

Roman Coleman (Matthias Schoenaerts, Rust And Bone) spent a long time in isolation, away from other imprisoned men, but it’s time for him to re-enter the general population. Asked repeatedly by a psychologist (Connie Britton) what he’d like to do, he can only say that he’s not good with people. So she settles him on “outdoor maintenance,” which at this rural Nevada prison means shoveling shit. Horse shit, to be precise. There’s one horse that none of the convicts working in the wild mustang training program have been able to break, and Roman finds himself drawn to that wildness, a fascination spotted first by the program’s head (Bruce Dern) and then by one of its more skilled participants, aforementioned jocular old-timer Henry (Jason Mitchell, Mudbound). It becomes a solace, an honest rehabilitation that offers relief from the machinations of Roman’s cellmate (Josh Stewart) and the grief-stricken reproofs of his daughter (Gideon Adlon). Yet how can a person help to curb the terror and fury of a horse when he doesn’t even know how to curb his own?

It’s all well-trod territory. And yet—and here’s another cliché—The Mustang breathes new life into most of those conventions, thanks in no small part to Schoenaerts and his remarkable work. Normally, with a performance as spare as this one, one might use the word “restrained,” but here, it’s Roman who seems to be holding back, and not the actor. Schoenaerts plays the character as a man constantly on the verge of eruption; as such, his silences and blank expressions have the effect of a bare wall, imperceptibly trembling from the force of whatever’s wailing away at its other side. The few moments in which that wall gives away are no less effective. The actor’s vulnerability—and no less importantly, his physicality, which makes Roman’s journey as clear as any piece of dialogue ever could—lends an indispensable gravity and immediacy to The Mustang. Yes, this story gets told a lot, but it’s happening here, and to him.

The rest of the cast employs a similar approach, using the mechanisms these characters rely on to make it through the day to keep the film’s prison story grounded in the real. There’s precious little melodrama, just people with short tempers and ready compassion. The standout is Adlon, who plays Roman’s pregnant daughter, Martha, as a young woman who has to work very hard to remain composed when seated across a table from her father. The exception is Stewart, who sets the dial on his character’s menace at about a nine from the go, then cranks it well past 11.

He’s not aided by the writing there. The screenplay, which de Clermont-Tonnerre cowrote with Mona Fastvold and Brock Norman Brock, stumbles with Stewart’s character, Dan, an instigator of a racist gang war that concerns the sideline Henry (Mitchell, excellent as always) runs out of the mustang program’s medical supply room. But if the script requires some patience and tolerance, its clichés doing few favors to some of the subplots, the film’s visual splendor is a tonic. Cinematographer Ruben Impens approaches The Mustang with the same level of thoughtfulness he brought to Julia Ducournau’s Raw—a willingness to enter a space or a story we think we already know, and turn it all slightly on its head. A Western is always a Western, but Impens and de Clermont-Tonnerre play with perspective, angle, and color, and they know when to embrace sentimentality and when to approach the material with refreshing frankness.

That last choice sits at the heart of the film’s ending, a sequence that would in nearly any other story smack of the trite and the manipulative. Here, it’s matter-of-fact, and thus hits as hard as—forgive one last obvious choice—hooves pounding away at a gallop. If nothing else, The Mustang demonstrates that no narrative has become so hackneyed it can’t offer anything of value. Both broken people and tired stories sometimes deserve a shot at rehabilitation.