Bear with Ben-Hur. At first, the new adaptation of Lew Wallace’s New Testament soap opera seems impersonal, as dusty and ornamented as any movie in which robed Jews and Romans argue about gods and kings in accents of vaguely British origin. But wait, because there will come a moment when the hero is accused of conspiracy and sentenced to row a warship as a slave—at which point the movie jumps forward five years, into a terrifically grotesque galley sequence, with Jack Huston’s Judah Ben-Hur abruptly transformed from a princely non-entity into a long-haired, dirt-seamed wild man of vengeance, his voice permanently hoarse.

From the galley slaves’ point of view (which is all this Ben-Hur shows), the Roman trireme is an insane war machine, where orders to row are repeated from above even as arrows zip through the oar-holes and hot tar drips from the deck, until an armored ship’s bow with a screaming prisoner tied to the front rams through the hull. Suddenly, Ben-Hur is in the water, shackled to a hundred drowning oarsmen by a single chain—and then he’s washed up, reborn on the beach, surrounded by the white Arabian horses that will lead him in the climactic chariot race, where he will have his revenge.

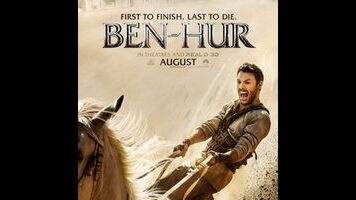

This is the point where Ben-Hur announces itself as the sort of elemental re-imagining of the source material that no one in their right mind would ever expect it to be. Director Timur Bekmambetov (Wanted, Night Watch) finds gothic currents in John Ridley and Keith R. Clark’s simplified script: a nobleman returning from certain death to race in the arena. This is a brooding, lamp-lit Ben-Hur who wears his hair past his shoulders. He is betrayed by Messala (Toby Kebbell), the Roman with the scar that runs from his temple to the tip of his ear. He is usually depicted as Judah, Ben-Hur’s best friend, but here is imagined as his adopted brother, so that the betrayal of the House Of Hur becomes a familicide. As Ben-Hur returns, it even snows in Jerusalem.

Wallace’s Ben-Hur is hardly a great work of literature, and every adaptation has struggled with its central rivalry; the extent of the homoerotic subtext in William Wyler’s definitive 1959 film version is debatable, but it’s the only reading under which Messala’s betrayal of Ben-Hur makes any sense in that film. In the new version, Messala goes away to war to prove himself (in a montage that indulges Bekmambetov’s taste for grungy sword-and-shield combat), returning as a paranoid and emotionally remote gung-ho Roman who doesn’t think twice about condemning the family who raised him after a would-be assassin fires an arrow from their balcony.

Ben-Hur escapes the galleys similarly disassociated, thinking only of revenge. (It was Wallace’s novel that popularized the image of the whipped galley slave; Greek and Roman triremes used professional oarsmen.) Factor in grumblings about how the Roman occupation would have less trouble keeping the peace if they understood local religious customs, and you have the makings of an allegory for a more recent Middle Eastern intervention, which Ben-Hur pursues indifferently. Of course Jesus is around somewhere: a hunky messiah (Rodrigo Santoro) who is only a little less laughable than the chestnut-haired figure who always has his back to the camera in Wyler’s version.

But really, it’s all about the story’s symbolic baptisms and Bekmambetov’s askew wide-angle compositions. Ben-Hur frees himself from slavery in the water to become a force of retribution, and then has his moment of conversion in a rain storm on Golgotha. He is swept out of the Ionian Sea and straight into the hands of Ilderim (Morgan Freeman), who is headed for the new hippodrome in Judea and could use a man who knows horses, fating our hero to race against Messala through clouds of dust.

The Wyler film’s rousing chariot sequence—filmed separately and at lavish expense by Andrew Marton and Yakima Canutt, one of the greatest stuntmen who ever lived—is hard to beat. But Bekmambetov acquits himself nicely, offering up a loud and vicious circular chase, with point-of-view shots of people getting hit by chariots as armored Romans scamper around like rodeo clowns. From the mouth of its cluelessly evil Pontius Pilate (Pilou Asbæk), it offers what could be a curtain line for a downer ending, before remembering that there are some minutes left until the end credits, and the movie has a Son Of God to crucify and a soul to save.