The new face of the home invasion thriller is black and female

Note: This piece discusses plot points of The Intruder, Breaking In, No Good Deed, and Us.

Did I lock the door before settling into bed? How about that closet? Was it always ajar, or did someone find their way in there to watch—and wait?

The fear of unknowingly being watched is a deep and primal one, and it’s been reflected time and again on the big screen. But even more frightening than simply being watched—something the government has already been doing for years—is having one’s seemingly safe personal space invaded. That’s why it’s easy to wonder if your doors are locked before falling asleep, and why videos of ghostly figures on security cameras give us the creeps. We fear the unknown, and an outside force abruptly disrupting one’s normalcy in a chaotic, uncontrollable invasion is even more frightening. That’s where the “intruder” trope comes in.

One of the first known American films to take a stab at the trope was D.W. Griffith’s The Lonely Villa. Released in 1909, the black-and-white, eight-minute short tells the story of a young, wealthy man who is lured out of his home by thieves, while the man’s wife and children hide in a room in hopes of escaping discovery. Lois Weber’s Suspense, released in 1913, took a similar look at the intruder trope, this time with a woman in the lead who’s forced to defend her remote home from being invaded. The Lonely Villa and Suspense are as thrilling as films created more than 100 years ago can be, but more importantly, they showcase—in 10 minutes or less!—the cultural fear of unknown faces upending the perfect white family.

Despite their short running times, The Lonely Villa and Suspense are thought-provoking because they reflect the cultural fears of early 20th-century white America. The Lonely Villa shows a wealthy white family’s life turned on its head for the sake of greed. In Suspense, the villain is unshaven, dirty, and dressed in clothing that reflects the disparities between him and the family he intends to kill. He is the “other” lurking in the shadows, watching a nice white family walk home at night. These films’ use of the trope can be generalized to reflect a clear, common fear of white comfortability, predominantly symbolized here by the home, being invaded by the “other”—people of another race, class, or nationality. In the century that has passed since then, not much has changed.

Between the release of The Lonely Villa in 1909 and today, many cinematic attempts have been made to address this generalized fear of the “other.” Audrey Hepburn was nominated for her an Oscar for her portrayal of a blind woman battling three men trying to rob her New York home in 1967’s Wait Until Dark. And who can forget the iconic “Have you checked the children?” tagline for 1979’s When A Stranger Calls?

Historically, home invasion films have put young, pretty white women at their center: The genre lives and breathes on their shrill screams while hiding in closets, as well as the classic “I’m in a tank top and sweating my ass off, but I’m fighting back, dammit,” scene. But in the last 10 years, there’s been a shift in the narrative. The home-invasion tropes remain the same, but the lives of those at risk are less white and male as African-American women have taken the trope and made it their own. The classic jump scares remain, but now the protagonist trying to regain safety amongst complete chaos is a black woman protecting her child or her husband from the wrath of—in most cases—a white man.

Released in theaters last month, The Intruder’s take on the home invasion genre isn’t revolutionary, but it does highlight the power struggle between white men and anyone who gets in the way of giving them what they want. The Intruder follows Scott (Michael Ealy) and Annie Russell (Meagan Good), an affluent African-American couple who purchase a home from Charlie Peck (Dennis Quaid), a widowed white man. Charlie is possessive and domineering; even after selling the home, he appears at the Russells’ doorstep unannounced and unabashed. The film is outrageous, but at the same time, it’s not. Think of the home as America: Charlie, a white man, views it as rightfully his, and its new residents as intruders. We see it in the news now more than ever: young white men acting foolishly and dangerously to protect what they believe is “their” country. In this way, The Intruder flips the cultural fear of intrusion by placing the African-American couple inside the home, examining what it means when a black couple who have worked hard to achieve a nice home and nice cars are terrorized by a force that believes it should still not rightfully be theirs.

2018’s Breaking In and 2014’s No Good Deed also examine intrusion from the perspective of African-American families terrorized by outside forces, but these films place women in the lead. In Breaking In, Shaun Russell (Gabrielle Union) travels to her recently murdered father’s secluded home, hoping to sell it. Unbeknownst to her, a gang of men are already in the home and plotting to steal $4 million. When she steps outside for just a moment, the men hold her children hostage, demanding the money in exchange for her children’s lives. That’s when all hell breaks loose. While the men are cunning, Shaun is two steps ahead. She climbs roofs, she points knives at people’s throats. She does what it takes to save her family from intruders, even if that means killing the threat at hand.

In No Good Deed, escaped convict Colin Evans (Idris Elba) arrives at Terri Granger’s (Taraji P. Henson) home on a rainy night and asks to use her phone; after putting together the unlikely series of coincidences that connect them, he decides to make Terri and her child his next victims. Other than her initial mistake of letting a stranger into her home, Terri is quick to act on her instincts, and once she realizes she has been wronged by not only the man she trusted to enter her home, but her husband as well, she grabs a gun and shoots the intruder without hesitation. It’s her life versus a stranger’s, and she refuses to let a man win this time.

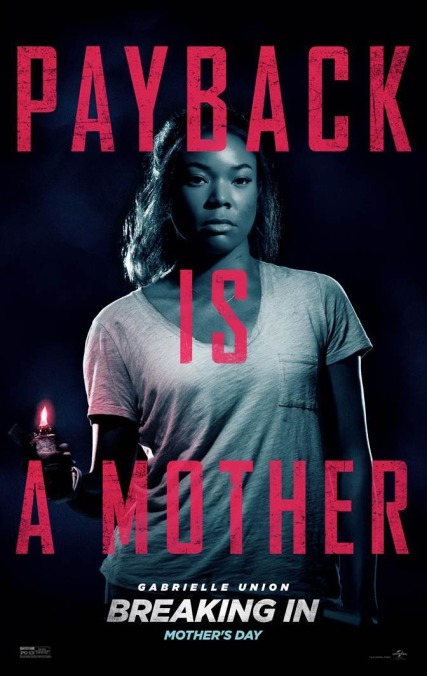

Black women have often been portrayed as loud and abrasive in film, particularly in the thriller genre. They are usually outspoken, and pay in the form of death for their suspicion of outsiders (see Scary Movie for a comedic portrayal of this trope). In No Good Deed and Breaking In, they are the exact opposite. Both Shaun and Terri have human faults. They are strong and weak at the same time, and they make mistakes in the face of fear, but they are willing to defend their children even if it means imminent death. The hook used to promote Breaking In was “Payback is a mother,” with posters featuring a defiant Gabrielle Union. As in most thriller films with women as the lead, there is always a breaking point. By having strong black women lead No Good Deed and Breaking In, the intrusion trope is fixed to question what it means when men attempt to force their way into a woman’s life—and, specifically, what it means when they try to interrupt the everyday lives of a black woman and her children.

But perhaps the grandest examination of intrusion from a Black perspective is in Jordan Peele’s Us. In Us, the Wilson family is terrorized by the “tethered”—underground clones of themselves that symbolize the darker, corrosive versions of ourselves that we ignore in search of the greater good that lies within. Peele’s films place black lives in the forefront to address cultural, racial, and economic issues. He places a black woman in the lead and showcases how far a woman would be willing to go to protect her loved ones. Lupita Nyong’o takes her role as a mama bear to the next level by not only portraying a woman fighting to save her family from the unknown, but—if you flip the film to see it from the “tethered” perspective—a woman attempting to give her family a chance at a better life. Us is filled with symbolism and clever plot devices, but the image of a black woman fearlessly fighting to the death for her family—even while handcuffed!—brings the film to new heights. In the face of terror, she stares back defiantly. She literally travels to the end of the world to save her child.

As the political climate continues to heat up—both literally and figuratively—we can only wonder if the home invasion theme will continue to grow as much as it has in the past century. And as a new, diverse set of directors and writers enter the Hollywood sphere, hopefully the narrative will continue to be redefined. Placing African American women in the leading role of thrillers not only unites a wider audience, but provides thought-provoking moments that create space for an audience to ponder what it means socially when black and white women are written differently placed in similar scenarios. There’s plenty of room in the Hollywood sphere for faces from different cultural and racial backgrounds, and the rise of the black woman as the face of the thriller genre is a great way to start.