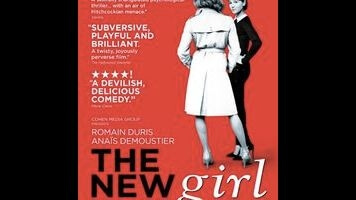

Much of the credit for that goes to Ozon, who has taken Rendell’s rather chilly little thriller (which won the Mystery Writers Of America’s prestigious Edgar Award for Best Short Story) and created something considerably warmer and more empathetic. Here, the inciting incident is the death of a young woman and the feeling of loss it inspires in her best friend, Claire (Anaïs Demoustier, from last year’s Bird People). One day shortly thereafter, Claire impulsively decides to check in on the widower, David (Romain Duris), who’s caring for the couple’s newborn child—and is startled to find him dressed in his late wife’s clothes. She quickly accepts the situation, however, and soon Claire and Virginia, as the feminine incarnation of David calls herself, have become inseparable. And since David isn’t gay—or maybe it’s more accurate to say that Virginia is gay, or maybe it doesn’t really matter—they soon become lovers as well.

Because Virginia, as a character, is sometimes played for laughs (Duris has an unfortunate tendency to ham it up even when he’s not in drag), The New Girlfriend risks coming across as insensitive, if not actively offensive. Ozon’s track record in this department shields him from such criticism, to an extent, but the deciding factor is his clear affection for David/Virginia, who cuts a less pathetic, more vulnerable figure here than in the original short story. There’s never a sense that (s)he’s being belittled or judged. The real problem is that Ozon can’t quite decide whether he’s making the crowd-pleasing tale of a cross-dresser’s empowerment or the thornier, more compelling tale of a woman who tries to recreate her dead best friend, Vertigo-style (and then sleep with her). Elements of both tales feature prominently, and they constantly get in each other’s way; the movie keeps feinting toward complexity and then retreating into fabulousness. Arguably, Ozon is too sensitive a filmmaker to take on a sharp-edged author like Rendell. But one could also argue that her sensibility is dated, whereas his, however muddled, is very much au courant.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.

Keep scrolling for more great stories from A.V. Club.