The Night Manager is elegant, well-chilled spy craft

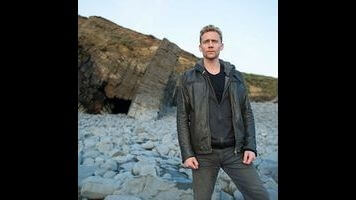

There’s something fundamentally compromised about a Tom Hiddleston character. The actor has all the signs of the classic cinematic heartthrob: crisp, fit, with an impeccable British accent and an easy smile. But something about that smile is slightly off—turn a few degrees north and it looks like a wince. As Jonathan Pine, eponymous night manager and fledgling spy, Hiddleston is likable, suave, and imminently capable. Yet he never quite shakes the impression of weakness that dogs him throughout—the shadow of a man who failed his great test in life, and is doomed to spend his remaining days grinning through the wreckage.

It’s a quality The Night Manager never fully capitalizes on. Pine makes his share of mistakes, but at heart he’s a decent man struggling to do his best in a broken and corrupt world. Yet Hiddleston’s inherent qualities as an actor help provide the show’s protagonist with some much needed depth. It’s not so much that Pine on his own is a walking cipher—just that, as with nearly every other character in the series, he is more or less exactly what he appears to be at first glance. The suggestion of texture helps considerably, even if it isn’t necessarily supported by the text.

Which isn’t to say The Night Manager is a bad, or even a boring, six hours of television. An adaptation of a 1993 novel by John Le Carré, the show has all the familiar Le Carré hallmarks: a cynical worldview, an understanding of the price the powerless pay for the sins of the rich, and a view of espionage that’s at once thrilling and brutally mundane. The plot is complicated enough to keep from lagging but rarely difficult to follow, and the long running time allows for plenty of room for every beat to breathe.

Inevitably some of that breathing goes on for too long, which is where the relative straightforwardness of the ensemble becomes a concern. A spy story in which it’s possible to accurately judge nearly everyone at face value is one that sacrifices one of the genre’s most effective tools. The series follows Pine as he works to ingratiate himself into the inner circle of notorious arms dealer Richard Roper (Hugh Laurie), hoping to ferret out the necessary information to shut Roper down for good. At times it plays like an extended James Bond outing, with a protagonist enjoying the fruits of venal labor even as he plots to bring down that venality from within.

The narrative’s pleasures rest less on unexpected incident (of which there are only a handful), and more on the thrill of watching Hiddleston square off against Laurie and the rest of his crew. As Roper, Laurie is plainly enjoying himself, playing the sort of villain who never seems to be short on an ambiguously threatening phrase, even as his cunning rises and fails to the needs of the plot. As Roper’s second-in-command Major Lance Corkoran, Tom Hollander does the best he can with the character as written, self-pitying and morbidly campy in a bizarrely dated fashion; Corkoran’s homosexuality is treated as a kind of tragic character flaw in a way that’s borderline absurd. And as Roper’s pay-for-play mistress Jed, Elizabeth Debicki does the best that can be expected with a curious mixture of femme fatale and damsel in distress.

Rounding out the cast is Olivia Colman as Angela Burr, Pine’s handler back in London. Burr was a man in the original novel, and the change is one of the adaptation’s smartest decisions, mostly because it allows for Colman to be cast in the role. Her world-weary determination marks her as an ideal toiler in Le Carré’s world, someone doomed to professional disappointment in a job that doesn’t really deserve her. Her scenes at home also come the closest to offering something more than a vision of good and evil, as she fights against the forces in her own government who want to keep Roper about his business.

Apart from some tweaks to the ending, the adaptation’s other major change to the source material is pushing it forward two decades and updating the politics to match. The first episode begins in Cairo, Egypt at the height of the Arab Spring, and Roper’s arms dealing seems to be a primarily Middle Eastern concern. It’s a decision that’s at once relevant and oddly moot—the details may change, but the essential business of Anglo-Saxons profiting off a misery they share no part in remains the same.

Accusing any story of wearing out its welcome can be a tricky business. In some cases, necessary cuts are obvious, but with The Night Manager—aside from a detour or two—there’s no glaring missteps. The series is well-made and well-acted throughout, and if it’s rarely thrilling, it’s also rarely dull. Hiddleston and Laurie glaring at each other makes for a pleasant diversion, and Colman’s exertions are almost enough to wish the character had a show of her own. Roper is never much more than a menacingly jovial monster, and Pine never earns the soulful self-loathing Hiddleston brings to the role. But there’s something to be said for surface pleasures, especially when they’re this well dressed.