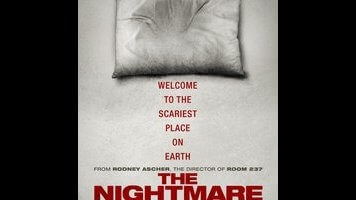

Sleep paralysis ranks among the most terrifying experiences a person can have, especially if you don’t know what it is and why it’s happening. The first time it happened to me, I felt panic so extreme that it was physically painful. Even now, many years later, I still get anxious during every episode, even as I remind myself that my inability to move a muscle is temporary (for me, it usually lasts a minute or two), the result of a minor processing glitch. And I don’t even hallucinate. Many people do, and it’s a few of those folks who recount their stories in The Nightmare, Rodney Ascher’s second documentary about a horror film. In Ascher’s previous effort, Room 237, the horror film in question was Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Here, it’s a movie created by each individual’s brain, tailor-made to scare the living shit out of them.

Because Ascher is primarily interested in what his subjects go through, The Nightmare doesn’t spend much time explaining sleep paralysis from a neurological standpoint. (Short version: We’re all paralyzed while asleep—an adaptation that arose, it’s believed, in order to prevent animals from acting out their dreams—and sometimes voluntary muscle control either switches off a little too soon or switches back on a little too late, while the person is conscious.) Instead, the film conducts talking-head interviews in which eight people (all of them American or British, though the phenomenon is universal) describe their experiences, which Ascher supplements with spooky recreations of what they describe. There are recurring elements among some tales, like a figure of pure shadow who either stands observing from a corner of the room or (in the freakier cases) slowly approaches the paralyzed victim and hovers menacingly right overhead. Other stories, like that of a guy whose penis is attacked by a giant mechanical claw, are bizarrely specific.

One of the problems Ascher faced in tackling this subject is that people suffering from sleep paralysis are paralyzed, and hence visually indistinguishable from people who are just asleep. (It can happen with your eyes open, but that’s somewhat rare, at least in my personal experience. Most of my time paralyzed is spent struggling to open my eyes; the moment I succeed, I can move everything else as well.) His sensible solution is to cheat a little, having the actors twitch desperately to signal their fear and panic. In any case, he’s not really striving for realism here: All of the recreations are shot on the same soundstage, and throughout the film Ascher deliberately calls attention to the artifice involved, showing actors dressed as bogeymen moving from one bedroom set to another, or showing the crew, or showing himself. The human brain, this movie suggests, is the ultimate horror-movie director, and sleep-paralysis hallucinations are just an extreme form of the standard-issue nightmares we all unwillingly create on a regular basis. It’s one thing to be tormented. It’s another thing to face the grim reality that you’re tormenting yourself.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)

![HBO teases new Euphoria, Larry David, and much more in 2026 sizzle reel [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/12100344/MixCollage-12-Dec-2025-09-56-AM-9137.jpg)