The normally infallible Dardennes trip over The Unknown Girl’s murder mystery

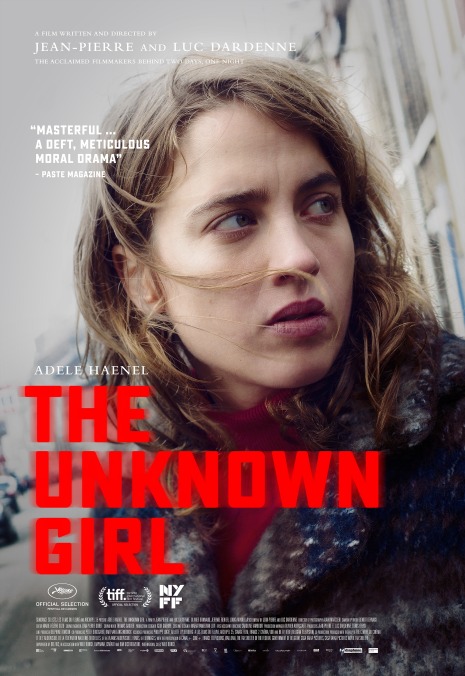

They find her down by the banks of the Meuse: a teenager, dead from a blow to the head, no identification on her. She is the unknown girl of The Unknown Girl, and though we really only see her twice, in a photograph and in a quick flash of surveillance footage, she casts a long shadow over this latest drama from acclaimed filmmaking duo Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne. Certainly, her death haunts Dr. Jenny Davin (Adèle Haenel), who takes it upon herself to put a name to the unclaimed body. It’s the least the young doctor can do, having unwittingly ignored the girl’s final cry for help—an after-hours buzz outside the doors of her practice. Maybe, in her attempts to identify this Jane Doe, Dr. Davin will also shed some light on her death. Maybe remorse will breed justice.

In theory, the idea of the Dardenne brothers making a murder mystery is exciting. Aren’t these master dramatists also low-key masters of suspense? The Son, arguably the Dardennes’ masterpiece, is almost unbearably tense—a slow-burn character study whose urgency hinges on whether or not it’s going to suddenly transform into a revenge thriller. And many of their other acclaimed dramas, from L’Enfant to The Kid With A Bike, feature passages of Hitchcockian tautness. But detective stories, even ones about part-time detectives, require a certain intricacy of plotting, and that’s never been a strength, or even a concern, of these Belgian writer-directors, whose movies tend to unfold straightforwardly, like moral parables. The Unknown Girl isn’t just their first bona fide thriller. It’s also the first Dardenne film in more than 20 years that could reasonably be described as less than exceptional, even a little clumsy.

That’s a relative distinction, of course. When you set the bar as high as these festival darlings usually do, even a minor misstep can feel like a big disappointment. In The Unknown Girl, the brothers’ durably direct technique shines, even when their storytelling doesn’t. Wracked with guilt about a death she didn’t cause but could have prevented—she assumed, without looking, that the buzz at her door was just a patient who showed up too late to get a walk-in appointment, not someone fleeing for her life—Dr. Davin launches an amateur investigation, if only to assure that the girl gets a proper burial and that whatever family she has knows she’s gone. Ever the ambulatory observers, the Dardennes track her progress across Liège, Belgium, as she chases leads and uncovers clues about the deceased, who turns out to be an African immigrant and a prostitute. (It’s no wonder, the film subtly suggests, that the police don’t seem too determined to crack the case.)

Although her crusade for information is blatantly an act of atonement, Dr. Davin still approaches it with a certain detached professionalism. Her occupation isn’t an accident; the Dardennes seem at least secondarily concerned with the regular battle between a doctor’s natural inclination to help (to usually open her doors, so to speak) and the necessity to sometimes go “off duty” for the sake of sanity. Dr. Davin makes house calls, even squeezing former patients into her busy schedule, but she also stresses the importance of keeping some emotional distance—a lesson she imparts on a young, anxious intern (Olivier Bonnaud) in what qualifies as the rare subplot in a Dardenne movie. To this end, it’s tough to say whether Haenel’s characteristic aloofness is a benefit or a drawback: Although it makes sense for this empathetic but pragmatic character, the French star (House Of Pleasures, Water Lilies) at times comes across as so emotionally removed that the film might well have been called The Unknown Woman.

There is some fun in seeing the Dardennes lean into genre, applying their sturdy style (handheld camerawork, no music, unaffected performances) to noirish scenes of the doctor tailing a potential source or being threatened by a couple of rough customers who don’t appreciate the kind of questions she’s asking. But as a whodunit, The Unknown Girl is unsophisticated and sometimes implausible; it hinges on coincidences, on chance encounters with characters who end up proving improbably involved. The Dardennes flirt with unintentional comedy here and there, as when Dr. Davin uses her medical expertise like a makeshift lie detector, determining that someone knows more than he’s letting on by reading his quickened pulse. And any student of Ebert’s Law Of Economy Of Characters, which states that name actors always appear in significant roles (even, or especially, when the roles don’t seem significant at first), might recognize the guilty party the moment they show their relatively famous face.

Given what we learn about the victim, it’s possible to read the film as a study of responsible citizenship: While others grow sick with the ache of their consciences, Dr. Davin converts guilt—specific to her fatal if fleeting indifference, more implicitly a recognition of her privilege—into tangible action. Instead of just feeling bad about what she could or should have done, she tries to make amends. That safely places The Unknown Girl alongside the other redemption dramas that make up the Dardennes’ largely peerless filmography—like their earlier work, it’s about moral crisis and how it can be resolved. There’s just something a little too expected and even predictable about how the absolution arrives this time. The most surprising thing about the film is how few surprises it packs. That’s unusual, coming from the Dardennes. And it’s downright detrimental in a mystery.