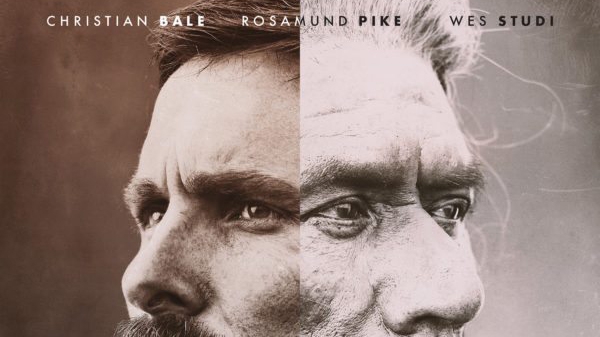

The Old West is clinically depressed in the grim Christian Bale oater Hostiles

Hostiles—a twilight-of-the-frontier Western as grim and obvious as its title and tagline (“We are all… Hostiles”), filled with greasy skin and scraggled, dimming landscapes—opens with a Comanche band gruesomely descending on a remote homestead and American soldiers torturing an Apache family in the reddish Southwestern dust. The mix of violence and primeval American scenery is almost mystic, the victims screaming as they are sacrificed to the death cult of the revisionist Western. Dozens more will be butchered to appease the themes of director Scott Cooper’s script: the sin and apparent redemption of the American myth, complete with visual quotations from The Searchers. Like Cooper’s Rust Belt faux-noir Out Of The Furnace, it’s an exercise in strained seriousness, the potential ironies and dramatic tensions lost in a repetitive, episodic, and politically vapid narrative.

But in the middle of this bogus gravity—the clinically depressed American West, stuck in a cycle of fatigue, self-loathing, and self-pity—there is a wonderful scene, tucked like a letter in a dull book. The troubled hero, Capt. Joseph J. Blocker (Christian Bale, with a walrus mustache), has come to pay a final visit to one of his men before he continues on his semi-symbolic journey, knowing they will never meet again; the two soldiers are overcome by the moment, and tears well up in their eyes. There’s another sequence, less moving, but still memorable: Mrs. Quaid (Rosamund Pike), the sole survivor of the Comanche raid, wracked with inconsolable grief, tries to dig her children’s graves with her own bare hands as Capt. Blocker and his soldiers look on. These scenes belong in a richer film.

Set in 1892, Hostiles introduces Blocker as a hardened killer, a man of few words and many tormented looks, defined by his hatred of the Plains Indians he’s spent his career fighting. Under threat of court martial, he has been ordered to escort the Cheyenne chief Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi) and his family from a dusty prison in New Mexico Territory to a valley in Montana; the chief, who was once Blocker’s nemesis, is dying of cancer. With the Cheyennes tied up like prisoners, Blocker and his squad begin to slog northward, through a series of history lessons about the savagery of the West, fighting off both Comanche raiders and white bandits. Early on, they find Mrs. Quaid; later they pick up Sgt. Wills (Ben Foster), a psychopath who spells out the subtexts of Hostiles for viewers who may have fallen asleep. (For a film with a mountainous body count, it doesn’t move fast.)

Ditching the more stylized touches of Black Mass—his last film, a dully fact-based who-whacked-whom gangster script directed in part like a sexually ambiguous vampire movie—Cooper goes for post-1970s American neoclassicism, with plenty of campfire chiaroscuro and magic-hour lighting. The tastefulness almost makes one yearn for the quirky points of view that countless second-tier spaghetti Western directors once brought to this genre. The landscape is rugged and unforgiving: rocky slopes, arroyos, muddy pinewoods. But the texture, for better or worse, is all in the actors and the dirt seamed into their humorless faces.

Oddly, Blocker’s bigotry—the crux of his story, the whole arc of this personification of America’s bloody past—is the least intriguing thing about him, despite Bale’s otherwise fine performance. And though ostensibly central to the story, the relationship between Blocker and Yellow Hawk quickly recedes into the background as Cooper lavishes attention on Mrs. Quaid and Blocker’s bedraggled men—especially Sgt. Metz (Rory Cochrane) and Cpl. Woodson (Jonathan Majors), who act as the group’s conscience. Hostiles’ failure to develop its Cheyenne characters (played by Adam Beach and Bale’s The New World co-star Q’orianka Kilcher, among others) is conspicuous. At best, they’re one-dimensional; at worst, they’re silent props, leading to a misbegotten final scene that seems to dismiss the film’s own grace notes. Cooper can craft the odd moving moment, but the bigger picture eludes him—a serious problem when you’re working with a canvas as large as the American frontier.