The only thing interesting about Hemingway In Cuba is where it was shot

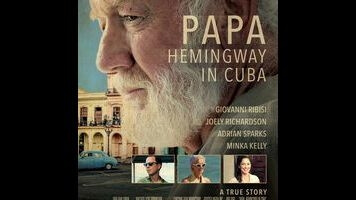

Only Nixon could go to China, and now, only Giovanni Ribisi can go to Cuba. As the first American production to be shot in the Marxist-Leninist republic since 1959—which also coincidentally happens to be the year in which it’s set—Bob Yari’s Papa: Hemingway In Cuba is significant even if it’s unlikely that it’ll open any floodgates. But novelty largely overshadows accomplishment. It’s the sort of film that’s destined to be the answer to a trivia question, and not much more.

Ribisi plays Miami Globe reporter Eddie Myers, a veiled surrogate for Denne Bart Petitclerc, who wrote the screenplay over a decade ago based on his experiences as Hemingway’s friend and confidant (and also wrote the film adaptation of Islands In The Stream). As the film opens, Eddie has written and junked dozens of fan letters to the great author, whom he idolizes for his style and artistic significance. Fortunately, Eddie’s girlfriend Debbie (Minka Kelly) is thoughtful enough to rescue one of these crumpled missives, and forward it on to Hemingway, who responds by calling the younger writer up with an invitation to go fishing. Ribisi is a bit long in the tooth to be playing a wide-eyed pup, but his expression when he realizes that it’s really the guy behind The Sun Also Rises on the other end of the line is affecting nonetheless. He inhabits Eddie’s reverence with aplomb.

When Eddie gets to Cuba, he finds a man who simultaneously lives up and down to his intimidating image. Introduced piloting a boat through crystal-blue waters, Adrian Sparks’ Hemingway certainly looks and sounds like the real thing: The actor previously played him onstage in a one-man show, and has the same hard eyes and profile. It’s an impressive impersonation, and a slyer film might have meditated on the role-playing that goes along with being an icon—the gamesmanship of being Ernest Hemingway, the two-fisted alpha male of American letters. But Papa is a straight-up docudrama, and so instead of interrogating its subject’s persona, it simply depicts it, one sloppily episodic scene after another.

Papa’s laziness is felt most strongly in its treatment of the Cuban revolution, which is used primarily as a prod for Hemingway to wax philosophical about life and death. (“I hate it,” he says of war, as if the position needed clarifying.) Thus the film’s most potentially interesting aspect—the fact that Cuba plays itself—is wasted. Whatever their veracity, the thriller-ish turns of the plot feel geared to break up the monotony of so many scenes of Hemingway boozing and bawling at the people closest to him, including his fourth wife Mary (played in a performance of considerable charm by Joely Richardson). And the final passages are almost totally bathetic, drenching Hemingway and his downward spiral in a sentimentality that’s unbecoming of his own brilliantly pared-down prose.