The original Planet Of The Apes series became more daring from movie to movie

With Run The Series, The A.V. Club examines film franchises, studying how they change and evolve with each new installment.

Let’s begin with the ending, which is what most people do when they think about the original Planet Of The Apes. For nearly two hours, 20th Century Fox’s 1968 adaptation of Pierre Boulle’s 1963 science fiction novel depicts a world gone topsy-turvy, where humans are inarticulate savages, and civilized society is governed by intellectual chimpanzees, officious orangutans, and militaristic gorillas. When a shipwrecked American astronaut named Taylor (played by Charlton Heston) goes in search of the secret of how this “planet of the apes” came to be, he discovers the crumbling vestiges of a familiar human civilization, including the remnants of the Statue Of Liberty. In an instant, he realizes where he’s been all this time: on a far-future Earth, laid to waste by nuclear weapons. The movie stops right there, abruptly, with just the sound of waves lapping incessantly against the shore as the screen fades to black.

This is one of the greatest twist endings in cinema history: a sharp sock in the gut worthy of The Twilight Zone (whose creator Rod Serling worked on early versions of the Planet Of The Apes script). But it only works as well as it does because it comes at the end of an otherwise skillfully crafted genre picture, balancing thrilling action and mind-boggling weirdness with moments of real poetry and political provocation. The last scene punctuates the film, but does so in such a way that different viewers could read it as a question mark, an exclamation point, or an ellipsis.

As soon as the box office returns starting piling up, Fox decided it had to be an ellipsis. Then the studio was faced with a dilemma: How could they possibly improve on a near-perfect science fiction film?

Planet Of The Apes was directed by Franklin J. Schaffner, who’d previously helmed the political melodrama The Best Man, and would later win an Oscar for 1970’s Patton. Screenwriter Michael Wilson—a former blacklistee who’d done uncredited work on the Oscar-winning 1957 adaptation of Boulle’s novel The Bridge Over The River Kwai—was called in to do the final revision on Serling’s earlier Apes scripts. The film boasted a classy cast that included Kim Hunter and Roddy McDowall as soft-hearted scientist chimps Zira and Cornelius, and Maurice Evans as gruff administrator Dr. Zaius. The daringly abstract Jerry Goldsmith score, the astonishingly expressive ape makeup, the exotic-looking simian communities, and Leon Shamroy’s sun-dappled cinematography all framed the movie as sophisticated and serious: an A-picture all the way.

In the decades since its original release, Planet Of The Apes has been scrutinized for what it has to say on class, race, war, human nature, and even justice. (A mid-movie scene where Heston’s Taylor is put on trial based on ape values feels like Wilson’s not-so-subtle comment about his experiences with the House Un-American Activities Committee.) But even critics and newspaper columnists in 1968 knew what was up with this film. It’s thematically rich—and intentionally so. Schaffner’s team wanted people to walk away thinking about what makes us human, and about whether we treat others as we know we should.

They then wrapped the whole package up with an image so memorable and searingly ironic that, in retrospect, trying to proceed any further in the story seems foolhardy, and destined to failure. That Fox went on to produce four more thoughtfully made, unusually profitable Apes pictures is something of a minor Hollywood miracle.

Granted, only the original Planet Of The Apes is a masterpiece. The other four are flawed to varying degrees—in some cases significantly. But despite rotating creative teams and increasingly smaller budgets, each Apes movie between 1970 to 1973 at least attempts to meet the challenge of the original’s depth and punch. The series never topped its first chapter, but the people who worked on it never stopped trying.

While it’s not the weakest of the batch, the first sequel, Beneath The Planet Of The Apes, is the one that seems most like a cynical cash-in… at least for about 45 minutes. Heston was unwilling to reprise his role of Taylor until producer Arthur P. Jacobs and Fox boss Richard Zanuck agreed to two conditions: that he’d have little more than a cameo role, and that his character would be killed off. The actor’s absence is felt throughout Beneath, because Taylor’s arrogance and cynicism is woven into the fabric of what the original Planet Of The Apes is about. (Critic Pauline Kael gushed about Heston’s performance, calling it both charismatic and satirical, describing him as “an archetype of what makes Americans win… [with] the profile of an eagle.”)

In need of a new human, director Ted Post and screenwriter Paul Dehn concocted a fairly nonsensical premise that sees the bland James Franciscus playing an astronaut named Brent, sent on the same trajectory as Taylor and his crew on a rescue mission. Leaving aside how anyone in the 20th century would know that Taylor might need rescuing in the year 3978—a question that challenges the whole point of the original mission, if viewers think about it too much—the movie’s initial repeat of the “human shocked by talking apes” arc lacks imagination.

But conversations among the filmmakers about how to match the ending of Planet Of The Apes inspired a mid-movie plot twist that elevates the entire picture. After escaping from the increasingly human-hating apes, Brent finds his way to Taylor, who’s trapped in the underground ruins of New York City, held prisoner by a cult of telepathic human mutants who worship the weapons that destroyed their civilization. What starts out as a disappointingly stale narrative retread becomes a lively commentary on two kinds of fanaticism—mutant nihilism versus ape bigotry—that culminates in the bleakest ending of the entire series, as a dying Taylor activates another nuclear bomb. A narrator then sums up our whole existence thusly: “In one of the countless billions of galaxies in the universe lies a medium-sized star, and one of its satellites, a green and insignificant planet, is now dead.”

The powerhouse finish to Beneath came about due to a series of fortunate accidents. With Heston wanting out of the series, and a disgruntled Zanuck having been fired from Fox by his own father, Daryl, everyone involved with the film seemed eager to burn everything down and salt the ground. Meanwhile, a reduced budget meant that the sets and effects teams had to construct new environments out of matte paintings and leftover pieces from the Fox productions Doctor Dolittle and Hello, Dolly!, which actually gave the film more of a retro science fiction look—like the covers to old pulp magazines come to life.

Where Beneath suffered most from its lower price tag was in the ape makeup. The genius of the best ape masks was that the applications kept the eyes clear enough to allow actors like McDowall and Hunter to carry plenty of emotion there (and then to do the rest of their acting by over-articulating with their faces, just enough to move the foam rubber). For the second film, the good masks were mostly reserved for actors with speaking roles, while the backgrounds were filled out with more shabbily outfitted extras. When Fox slashed the budget yet again for 1971’s Escape From The Planet Of The Apes, one of the solutions to the mask problem was to put only three apes in the film—and to kill one off in the first reel.

The reduced ape cast was also necessitated by a new and ultimately fruitful narrative direction. Having blown up the world of the late 3900s, producer Jacobs, screenwriter Dehn, and director Don Taylor imagined what would happen if some of the chimpanzees commandeered one of the spaceships that had crash-landed on their Earth, and traveled back through time to the early 1970s. (Again, don’t dwell on the wonky science.) Hunter and McDowall returned—the latter having sat out Beneath due to other commitments—to play Zira and Cornelius, who along with their doomed colleague Dr. Milo (Sal Mineo) arrive in Los Angeles in 1973, where they quickly become the subject of intense public fascination and concern.

A bright and entertaining movie that takes a dark turn, Escape From The Planet Of The Apes starts out as a gentle spoof of contemporary culture, as Zira and Cornelius become fashionable celebrities prized for their opinions on everything from art to war to feminism. But while the chimps are becoming stars, some people in the government question where they came from, and what happened to make them interplanetary orphans. With the help of booze and drugs, a presidential advisor coaxes Zira into spilling the whole story, which leads him to worry that the baby she’s carrying will eventually instigate an ape uprising against humanity.

It’s possible to see the first two Planet Of The Apes as one story, and the next three as another. The original and Beneath are about the long-overdue end of the Earth, after centuries of conflict and self-destruction. Escape and its two sequels tell how the downfall began, while also offering up glimmers of hope that Zira and Cornelius’ son, Caesar, can change the timeline and forge some kind of peace between humans and apes.

If the name “Caesar” makes fans of the new Planet Of The Apes movies perk up, well, that’s the point. The recent films—Rise, Dawn, and War—are loose analogs to Escape, Conquest, and Battle, the last three of the ’70s series. Both trilogies are about a kind of ape messiah named Caesar, born in humble circumstances and thrust into the role of a leader. He appears first at the very end of Escape, after the government guns his parents down. Under the protection of a kindly circus owner named Armando (Ricardo Montalbán), he learns how to read and write and articulate his thoughts, just as his mother and father would’ve wanted. While Caesar’s getting an education, human society begins its collapse.

Conquest Of The Planet Of The Apes tells the story of the big shift from human to ape, in what’s arguably the boldest film of the series. Conquest lacks the production value or complex storytelling of the original (blame more budget cuts, coupled with returning screenwriter Dehn’s simpler-is-better ethos). But director J. Lee Thompson brought more pure cinematic artistry to the franchise than anyone other than Schaffner, keeping dialogue to a minimum in order to draw audiences into the world of the still-non-speaking apes. Making good use of the recently constructed Century City—a former Fox backlot repurposed as ultra-modernist office buildings and shops—Thompson thrust viewers into a dystopian near-future, where apes have been trained to work as humanity’s servants.

When a mature Caesar (played by McDowall) arrives, he covertly begins organizing his fellow simians, working with them to gather an arsenal. Once the government realizes who this revolutionary chimp really is, they scramble to kill him before he can set in motion the apocalyptic future Zira once warned them about. What follows are large-scale scenes of violent clashes in the street, staged and shot by Thompson and his crew to resemble the race riots and antiwar protests that Americans were getting used to seeing on the nightly news. The movie persistently pushes buttons, with shocking images of slave auctions and open revolt that test where our sympathies should lie.

The result is the bloodiest of the Apes films, and one of the most despairing. The theatrical release included a softer ending—suggesting the now-ascendant apes would try to exhibit compassion toward the surviving humans—but the true spirit of the film is in its original, now-restored conclusion, where former slaves vow to humiliate and subjugate their former masters. That vision carries over into 1973’s Battle For The Planet Of The Apes.

Thompson became the first director to return in the series, but due to health issues, Dehn was reduced to an advisory role on Battle, turning screenwriting duties over to the husband-wife team of John William Corrington and Joyce Hooper Corrington. The finale is the worst of the five—though it has enough good scenes to remain watchable. The biggest problems are twofold: The action largely comes across as a repeat of things the franchise had done better before, and due to Dehn’s long-standing goal to bring the story full circle, Battle shoehorns in plot points and villains that are fairly ridiculous.

Set several years after Conquest, Battle depicts the new reality under Caesar’s rule, where some humans work for apes while others—already in the early stages of a mutation due to a nuclear war that occurred after the events of the previous film—nest in “the Forbidden City,” making plans for a revolt of their own. Meanwhile, Caesar and his simpatico orangutan assistant Virgil (Paul Williams) deal with dissension in their own ranks, as the hawkish gorilla Aldo (Claude Akins) proves willing to violate the “ape shall not kill ape” law if it means ending the pretense that simians and humans can coexist.

The Aldo/Caesar split is far more compelling than the war with silly-looking mutants—though it’s the latter that takes up the bulk of Battle’s running time. What Apes fans remember most about the last movie is its framing device, which has John Huston as the “Lawgiver,” previously seen in the first two films as a statue, representing the apes’ most revered ancestor. Speaking to an assemblage of young apes and human children in the year 2670—nearly 700 years after the events of Battle and 1,300 years before Planet/Beneath—the Lawgiver presents the story of Caesar as one with a happy ending. But then in the movie’s final image, a statue of Caesar sheds an ambiguous tear. Is his spirit happy that he changed the timeline and brought peace? Or does he know that the Earth remains doomed?

[Nerdy note: There are three major statues in this series, beginning with the Statue Of Liberty, continuing with the statue of the Lawgiver that sheds tears of blood when the gorillas are urging war against the humans in Beneath, and ending with the crying Caesar statue. In each case, it could be said that an object meant to memorialize the best of a species is doomed to witness its worst.]

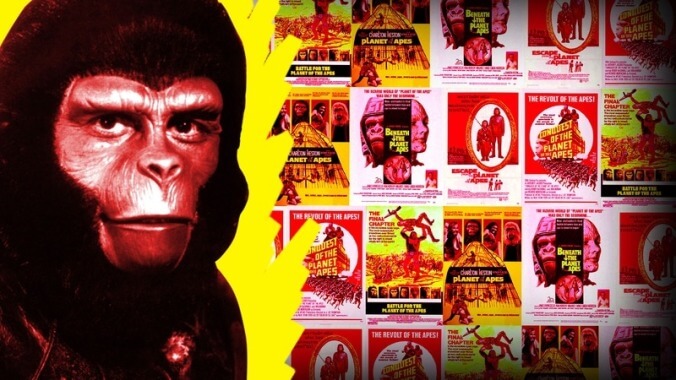

The legacy of Planet Of The Apes goes beyond what actually happens in the first five films. The franchise continued in two short-lived TV series—one live-action, one animated—and then found belated success as a merchandising phenomenon. In the mid-’70s, Fox programmed “Go Ape!” marathons around the country during dead spots on the theatrical calendar, and the popularity of those revivals (coupled with frequent TV reruns of the movies) convinced toy companies to crank out action figures, play-sets, model kits, board games, Halloween costumes, lunch boxes, and more.

To Hollywood, and to smart genre-minded filmmakers, the popularity of Apes paved the way for a lot of what would become the modern blockbuster—from the toys to the sequels. (The big difference: These days studios tend to pony up more money for each successive film in a series.) In the process, some of the sociopolitical nuances of the original series have been lost to non-fans, who only know about the parts that penetrated popular culture: the ape costumes, the twist ending, and Heston over-emoting.

So let’s end with the beginning—which is Planet Of The Apes at its best. Let’s go back to Taylor, a man so cocky that he smokes a cigar in an airtight space capsule, and then mocks his fellow astronauts’ sentimentality when they realize they’re stranded thousands of years in their own future. He warns them, “There’s only one reality left: We’re here and it’s now.” No matter who’s rising, who’s escaping, or who’s battling, this existential certitude remains the Apes movies’ most potent message. If nothing else, it reemerges every time a new group of filmmakers looks at the money to be made on another picture and wonders what it should say.

We’re here. It’s now. What’s next?

Final ranking:

1. Planet Of The Apes (1968)

2. Conquest Of The Planet Of The Apes (1972)

3. Escape From The Planet Of The Apes (1971)

4. Beneath The Planet Of The Apes (1970)

5. Battle For The Planet Of The Apes (1973)