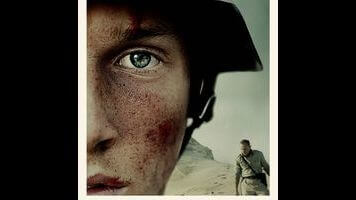

The Oscar-nominated Land Of Mine uncovers another World War II horror story

They’re boys, all of them: scrawny, scared, old enough to die for their country, too young to even grow beards. They crossed Europe as invaders, the smallest cogs in the German war machine. Now the war is over but not for these barely pubescent soldiers, forced into new service after being captured on the battlefield. To earn safe passage back to their homeland, they must perform a daunting task: clear away the active land mines buried along the coast of Denmark. They will spend all day every day on their hands and knees, sifting through sand and carefully disarming rusty explosives. They will receive little food and less kindness from the country their country occupied. When they’re injured—hands reduced to bloody stumps by the bombs on the beach—they will cry out for mothers that will never hear them. When they die, no one will cry for them.

It’s nothing new, expressing sympathy for those on the other end of the rifle; Grand Illusion, cinema’s most celebrated and civilized POW story, got there 80 years ago. But there’s still a hard-nosed integrity to any film that reserves some pity for the vanquished villains of World War II—at least the youngest of them, Germany’s veritable child soldiers—while still understanding how difficult it might be for a Nazi-ravaged Europe to see these boys as anything but the enemy, reaping what they violently sowed. The Danish drama Land Of Mine does just that, retelling one of World War II’s countless dark chapters: the cruel and unusual deployment of German POWs as land mine disposal units, blown to smithereens for the sins of their superiors.

We meet our main character, Danish Sgt. Rasmussen (A Hijacking’s Roland Møller), in the opening scene, pulling up to a long line of German soldiers marching out of Denmark in defeat. He beats one half to death for attempting to steal a flag. It’s not the flag he’s really furious about. The sergeant ends up in charge of an amateur bomb squad, shell-shocked kids tasked with a mission even more suicidal than the one Hitler assigned them. Land Of Mine gives some of them names and basic traits: Helmut (Joel Basman), too bitter or just too smart to believe he’s ever going home; twins Ernst (Emil Belton) and Werner (Oskar Belton), maybe the most boyish of the whole lot; Sebastian (Louis Hofmann), who might have been a leader in a different decade. But they’re not really characters, because they can’t be. The war has stolen their choices, their personalities, their futures.

Just a few years ago, The Hurt Locker made nerve-wracking spectacle out of bomb defusing. Land Of Mine has its queasy moments—scenes of shaky adolescent hands and finicky equipment—but it’d be hard to call the movie “exciting.” Director Martin Zandvliet doesn’t so much build tension as telegraph tragedy; if a shot or a tranquil conversation (many of the “What are you going to do when you get home?” variety) seems to last too long, you can usually be sure that an “unexpected“ explosion is imminent. Anyway, it becomes clear pretty quickly that we’re not waiting to see if the young grunts will survive but rather to see if any of them will. Most of the suspense relates to the sergeant’s motives. Will this decent man, embittered by the war, find some kind of feeling for his charges, digging their own graves in the dunes? Or does his hatred for their nation supersede any traces of compassion he may have left?

It’s easy to see why Land Of Mine is one of the five films competing for this year’s Foreign Language Oscar: It’s a handsome World War II movie with a clear emotional appeal and a clearer dramatic arc. (Plus, it’s Danish. The Academy often gets a Danish movie in there, for some reason.) But the cheesiest thing about it is the punny English-language title with which it’s been saddled. Otherwise, Land Of Mine is tough and admirably grim, turning a harrowing history lesson into a study in how the battles of wartime don’t always cease with the ceasefire. War is hell, real life and the movies tell us. But for the losing side, the aftermath can be plenty hellish, too.