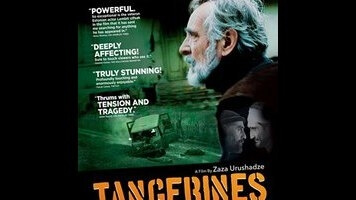

The Oscar-nominated Tangerines is more interesting before the bullets start flying

War makes for strange bedfellows in the Academy Award-nominated Estonian drama Tangerines, which is set in 1992, at the height of the clash between the Georgian government and Russian-backed Abkhaz separatist forces. Spurred by the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the armed conflict played out within Georgia’s borders as a full-on civil war—one that was nasty, brutish, and short. In lieu of a lot of social or historical context, writer-director Zaza Urushadze offers up a protagonist whose weathered and weary looks make him a plausible avatar of longstanding local trauma. As the film opens, sexagenarian Estonian woodworker Ivo (Lembit Ulfsak) has stubbornly opted to stay in his modest country shack in the disputed territory of Abkhazia, refusing to budge as chaos rages all around him. In case we didn’t know he was connected to the land, he’s given to helping his neighbor pick fruit off of the trees.

The battle literally comes to Ivo’s doorstep in the form of two soldiers—one Georgian, one Chechen, and both badly injured in a firefight—who Ivo takes in and treats with equal measures of tenderness and compassion as convalescents. His one condition is that they promise not to attack one another under his roof, which inaugurates an uneasy truce. The allegory here is not hard to understand: The warriors are mutually aggrieved and suspicious stand-ins for their respective factions, while Ivo, who claims no allegiance in the war, serves as a representative of a more enlightened viewpoint. Lean and tall, with wary, watchful eyes that always betray a basic kindness, Ulfsak is likable enough in the role to offset the fact that he’s playing a kind of idealized cipher—a peacenik screenwriter’s nobly sanctimonious surrogate.

The other actors are fine as well, and in its long middle stretch, which mostly involves Ivo playing peacemaker as his houseguests snipe at one another—sometimes humorously but mostly with murderous intent—Tangerines works well enough as a claustrophobically enclosed chamber drama. The problems begin when the idyll ends and the film starts to transform into a war film with dread-filled suspense sequences and shocking outbursts of violence, which feel cynically engineered to heighten the narrative stakes. The shift from philosophical parrying to actual combat doesn’t make Tangerines more compelling; on the contrary, it suggests that the filmmakers didn’t have the confidence to tell their story without falling back on genre tropes. That a small film about such a relatively unknown chapter of contemporary Baltic history has broken through to score an Oscar nod and an American release speaks to Tangerines’ accessibility, but what it delivers is ultimately less singular and specific than its arresting setting and scenario might deserve.