The Palm Beach Story is among the most pragmatic of screwball comedies

Preston Sturges’ The Palm Beach Story, newly released as part of the Criterion Collection this week, generally gets classified as a screwball comedy, and it definitely has all the hallmarks of that genre: the rapid-fire pace, the witty dialogue, the zany ensemble, the battle of the sexes. It also arguably fits the sub-genre that Stanley Cavell called “comedies of remarriage,” even though its primary couple never quite manages to get divorced (though not for lack of trying on the woman’s part). More than anything else, though, The Palm Beach Story, made just as World War II was finally putting an end to the Great Depression, is one of the most riotous movies ever made about money, with a pragmatic understanding of how difficult happiness can be when you don’t have any. Love does ultimately conquer all, in the Hollywood tradition, but only thanks to the assistance of multiple wealthy philanthropists.

Opening with the marriage of Gerry (Claudette Colbert) and Tom (Joel McCrea)—which Sturges, in the first of many madcap moves, shoots as if it’s the frantic finale of an earlier movie—The Palm Beach Story then jumps ahead several years to find the couple so broke that they’re on the verge of being evicted. Only the random kindness of an elderly “Wienie King” (Robert Dudley), who happens to be seeking an apartment in the building and insists on giving Gerry $700 (about 10 grand in today’s money), saves their skin. It’s too late, however, as Gerry has decided that both she and Tom will be better off if they split up—he’ll be able to live cheaply while struggling to get ahead, while she’ll be able to find another man who can provide for her. When Gerry flees to Palm Beach by train to file for divorce, Tom follows by plane (with more financial assistance from the Wienie King), only to discover that she’s already being wooed by gazillionaire John D. Hackensacker (Rudy Vallee), a blatant Rockefeller stand-in. Meanwhile, Hackensacker’s sister, the Princess Centimillia (Mary Astor), who thinks Tom is Gerry’s brother, attempts to engineer a double wedding.

Like a lot of movies made over half a century ago, The Palm Beach Story has some aspects that now seem cringeworthy. An otherwise amusing interlude on the train, for example, involving a rowdy group of millionaire hunters called the Ale And Quail Club, features demeaning depictions of black men that were commonplace at the time. What’s truly bracing is Gerry speaking frankly, again and again, about how she has to rely on her good looks to get what she needs. When an aggrieved Tom asks whether sex had anything to do with the Wienie King’s generous donation, Gerry replies, “Oh, but of course it did, darling. I don’t think he’d have given it to me if I had hair like excelsior and little short legs like an alligator.” At times, Gerry comes close to resembling a gold digger, whereas Tom remains noble and smitten throughout. But these depictions reflect an age in which marrying well was considered a woman’s most sensible decision, and they build to the scene in which she finally melts in Tom’s arms, cooing, “I hope you realize this is costing us millions.”

Sturges deftly manages to weave this social commentary into his usual tapestry of sheer manic pleasure. Hackensacker keeps a notebook detailing all the items he purchases for Gerry (which includes a bathrobe for $49.95—about $700 today!), but he’s introduced via a slapstick scene in which Gerry twice steps on his face, breaking two pairs of pince-nez specs, while trying to climb into the sleeping car just above his. Likewise, a scene in which Gerry attempts to flirt her way to a free train ticket serves primarily as a prolonged introduction to the eccentrics of the Ale And Quail Club, whose generosity comes with the price tag of a late-night a cappella performance that has their hounds howling in pain. Practicality and comedy don’t generally go hand in hand, but Sturges succeeds in making The Palm Beach Story as hilarious as it is realistic. Its happy ending insists again that a relationship devoid of money is an uphill battle, even as it abruptly introduces an absurdist twist that retroactively makes sense of the bizarre opening credits sequence. Mister, we could use a man like Preston Sturges again.

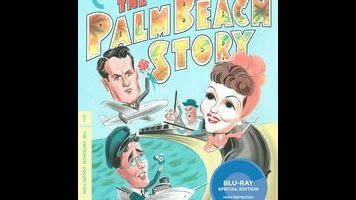

The Palm Beach Story is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Criterion.