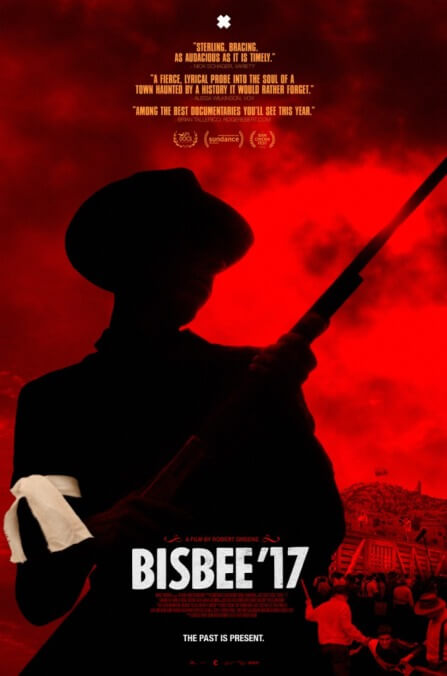

On July 12, 1917, roughly 1,300 striking copper miners—most of them recent immigrants—in the town of Bisbee, Arizona were rounded up at gunpoint, loaded onto cattle cars, transported 200 miles to New Mexico, and ordered never to return. A century later, documentary filmmaker Robert Greene (Actress, Kate Plays Christine) was on hand to observe Bisbee grapple with this historical event, which not every current resident considers a stain on the town’s legacy. The result, pointedly titled Bisbee ’17 (rarely has an apostrophe been more significant), straddles past and present in ways that would be plenty unsettling even without any knowledge of recent headlines. Like all of Greene’s films, it’s more of a cannily controlled meditation than a traditional attempt at semi-objective portraiture, deliberately blurring the line between documentation and performance. His last two features were explicitly about actors; this one transforms practically the whole of Bisbee into a memorably uneasy amateur theatrical production.

At first, Bisbee ’17 appears to be an oral history, albeit an unconventional one. Various residents recount their knowledge of what happened a hundred years earlier, derived either from research or from anecdotes passed down by previous generations. Some people—usually descendants of deputized posse members—still insist that Phelps Dodge, the mining company that engineered the deportation (in conjunction with the local sheriff), acted in the best interest of the town, preventing inevitable violence. Others see an indefensible act of blatant xenophobia exacerbated by corporate greed, and argue that reckoning with its shamefulness is long overdue. There’s little doubt about which side Greene favors, especially given that he opens the film with expository text stating, somewhat hyperbolically, that the miners were left to die. (They were given neither food nor water during the 16-hour journey, but were dropped off in what was then a tiny railroad town, Hermanas, and met there by an attorney for Industrial Workers Of The World; there’s no apparent evidence that anyone was actually trying to kill them.) Still, he allows each interview subject to make their case, honoring every personal perspective.

That bare description fails to capture the film’s sheer eeriness, however. For one thing, Greene, who’s ideologically opposed to any rigid distinction between cinematic fiction and nonfiction (all documentaries are in part fictional, he sensibly argues), can’t abide any pretense that he’s not mediating what he shoots. Here, he frequently lets the camera run for several discomfiting seconds before anyone speaks, or leaves it running well after someone has stopped talking, just to emphasize the performative aspect. This Brechtian approach makes more sense as the series of interviews get supplemented by scripted scenes in which residents act out, in period costume, the events of 1917. There are even musical numbers that play like a Billy Bragg fever dream. It’s similar to what Errol Morris did with last year’s Wormwood, except that here it’s the same people playing characters (sometimes their own dead relatives) and being themselves. Which Greene, in conceiving the project this way, implicitly suggests are one and the same thing.

The reenactment aspect culminates in Bisbee ’17’s grand finale, shot on July 12, 2017—exactly 100 years, to the day, after the Bisbee Deportation. Hundreds of residents dress up as posse members or miners, with the former herding the latter onto railway cars (an act that can’t help but call the Holocaust to mind, even though that happened decades later). As is the case with Civil War reenactments, or tourist attractions recapitulating Old West myths (Greene takes a quick detour in Tombstone to explore the latter), whether this exercise comes across as deeply cathartic or slightly silly will vary from person to person. One participant earnestly describes the experience as “the largest group therapy session,” and there’s a self-congratulatory, touchy-feely quality to this final movement that’s somewhat at odds with the earlier detachment. Also, the film turns more didactic, directly comparing Bisbee’s perception of immigrants a century ago—vaguely threatening, in need of removal—to recent actions of the Trump administration. Then again, should such a clear parallel be ignored, just because it’s so obvious that any reasonably well-informed viewer will tumble to it without prompting? That’s its own form of knowing manipulation (flattery, really), making it precisely the sort of thing that Greene likes to foreground. Most documentaries seek merely to inform. His always strive to make you interrogate what you’re watching.