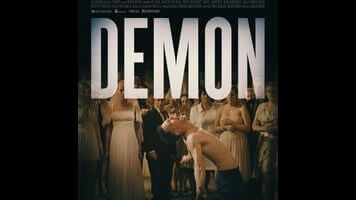

The past possesses a Polish wedding party in the mournful Demon

Less than a week after his third film, Demon, premiered to positive reviews at last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, director Marcin Wrona committed suicide in a hotel room just before its Polish premiere at the Gdynia Film Festival. It was a promising career cut short, as Wrona—who directed two films in Poland before making his international breakthrough with Demon—would not live to see himself hailed as the heir to Roman Polanski’s existentially unsettling art-horror throne.

It may seem morbid to ask viewers to go into a movie with the director’s untimely death in mind. But to fail to do so would be to ignore the lesson of Demon, a film where refusing to confront the past leads to the past coming back to confront us. The film takes place in a small Polish village, where Piotr (Itay Tiran)—a.k.a. Pyton—a laborer who has been away working in the U.K. for many years, returns home to marry Zaneta (Agnieszka Zulewska), the sister of one of his drinking buddies he’s never actually met in person. Zaneta’s parents are skeptical of the match, but Piotr is determined to win them over by restoring her grandfather’s house for himself and his wife to live in.

But this happy reunion soon turns ominous, after Piotr discovers what appears to be a human skull buried in his future in-laws’ front yard. We don’t see what happens to him alone in the abandoned house the night of the discovery, but it’s clear that when his buddies arrive, bottles of vodka in hand, for the festivities the next morning, Piotr is not the same person that he was the day before. As the film progresses, the demon of the title seems to eat away at lead actor Tiran from the inside, as subtle clues—a nosebleed, a quickly vanishing smile, dirty fingernails—eventually give way to more dramatic fits of possession.

The majority of the film takes place at Piotr and Zaneta’s wedding, in a series of stunningly executed set pieces that juxtapose the mad swirl of a Polish wedding with the dark revelations taking place just offstage. Alcohol and music are Wrona’s main tools to depict this happy ignorance, as the guests write off Piotr’s increasingly disturbing symptoms as drunkenness and the bride’s parents order the band to play louder to cover the sound of the groom’s screaming in the cellar below. This contrast is reflected in cinematographer Pawel Flis’ lens, which contrasts somber grays and sickly yellows with bright white lighting in the happy wedding scenes.

The horror elements of the film—which begin to creep in when Piotr spots a ghostly woman while giving a wedding speech but don’t really take hold until a while later—are pretty standard, with a local teacher speaking to the demon in Yiddish as its impromptu grave is dug up in the pouring rain. The stock wise man even explicitly tells us what we’re seeing: Piotr has been possessed by a dybbuk, a “clinging spirit” from Jewish folklore that attaches itself to a living person in order to carry out a mission or fulfill a promise that wasn’t achieved in the dead person’s life.

More interesting than the horror imagery is the film’s painfully somber message—no matter how far we try to run, the sins of history surround us always. In one (admittedly rather on-the-nose) scene, Zaneta’s father (Andrzej Grabowski) dismisses his daughter’s concern about the skull by saying, “the whole country’s built on corpses.” What he doesn’t understand is that same refusal to face the past—to acknowledge that the butcher shop was once a synagogue, and the empty houses by the river once had Jewish children playing in them—is why the dybbuk has comes back to haunt his family in the first place.

By the time we reach the frustratingly vague final act, the burden of centuries of sorrow and death may leave viewers of Demon feeling as broken down as the disheveled, drunken wedding guests on screen. And the film doesn’t offer any easy answers for younger generations confronting these crimes for the first time, either. It’s the kind of film that, rather like its mournful title apparition, clings to your sleeve and follows you home.