The Price Of Everything puts the complexities of the art world on breathtaking display

“I think there’s three kinds of people in this world,” says Amy Cappellazzo, chairman of the Fine Art division of Sotheby’s. “Those who see, those who see when they are shown, and those who will never see.” Seeing is the business of art, in the most sublime sense of the word. It asks the beholders to open their eyes and actively experience what they encounter. The flip side of that world is transactional, mercenary—in short, art’s other business is business. The master stroke of The Price Of Everything is that it asks the viewer, in Cappellazzo’s words, to see the intricacies of the art world and the way those two seemingly oppositional forces—the financial side and the creative side—are inextricably intertwined. It does not censure or lavish with praise. It takes events, realities, and points of view and hangs them on a vast white wall. Look, the film seems to say, and take from it what you will—but make sure you catch all the detail, because it’s not as simple as it seems.

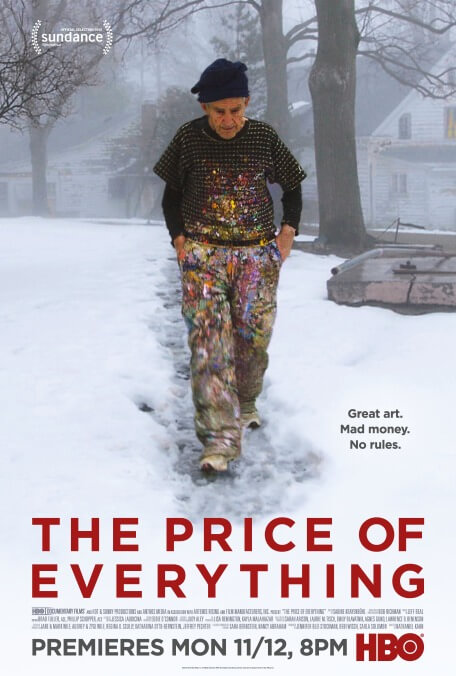

That sentiment may suggest a kind of remove, but The Price Of Everything is anything but distant. Filmmaker Nathaniel Kahn’s interviews with artists, collectors, curators, historians, critics, and other figures in the art world comprise the bulk of the film, and they throw the kind of sparks one might expect from flint against steel. Some of that is the natural result of passionate people digging into a particularly thorny issue that directly impacts what they hold most dear. Ask a critic or curator about masterpieces which disappear into the vault of a private collector, never to be seen again, and you’re likely to see their color rise or jaw clench a bit. But Kahn’s silence (the film includes no narration) is equally responsible for the undercurrent of tension. He does not comment, for example, on the financial savvy or marketer’s instincts that seem to have contributed to the staggering success of artist Jeff Koons. Nor does he offer an opinion on the choice of painter Larry Poons to abandon his lucrative trademark “dot paintings” when he realized that continuing to make them would, to him, have meant creative death. Koons is not “bad.” Poons is not “good.” They create, and are valued by others in both the creative and the financial sense; whether their approach is “right,” Kahn leaves for each viewer (and several of his interview subjects) to decide.

Some of the sentiments expressed are likely to infuriate, while others may inspire a kind of righteous assent. But while those interviews which directly contradict and seem to comment on each other may be the most engaging, it’s the conversations with figures who embrace those contradictions that prove most affecting. Art collector and plastics mogul Stefan T. Edlis, who unknowingly provides the film its title in one of his interviews, also proves responsible for much of the film’s emotional resonance, particularly in a thoughtful discussion of one of his acquisitions. Normally a description of an existing piece of art wouldn’t be something to hold back, but Edlis and Kahn both take a great deal of care when it comes to the Maurizio Cattelan sculpture in question (called “Him”): the former placing it with its face toward the wall, the latter honoring his choice by only revealing that face when Edlis explains his reasoning. There’s something quietly moving about Kahn’s decision to allow the viewer to approach the work in the manner Edlis intended, and yet still more affecting is the casual, easy way in which Edlis discusses how he experiences the sculpture, and its unexpected connection to his personal biography. Both serve to underline the power of the art, as well as Edlis’ impact on the art world, the chronicling of which makes up half the film’s climax.

There’s also the art, of course. A collector seemingly only interested in status and wealth can be bowled over by delicate color; a professional viewing acquisitions with the eye of a businesswoman might be enraptured by the painting that first sparked her interest in art. The film replicates those experiences with grace. Were The Price Of Everything just a tour of greatness, it would still be effective. But Kahn’s willingness to lay all these complexities bare, to ask both his subjects and the viewer to decide how culture, history, accessibility, meaning, and art itself can all be valued—and then to ask what value is, exactly—makes it a film well worthy of what it most celebrates: It, too, demands to be seen.