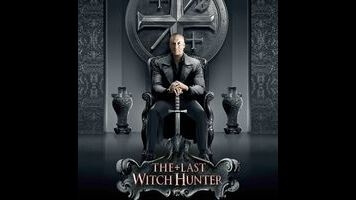

The pulp mashup The Last Witch Hunter is squandered potential

Rugged sword-and-sorcery heroes and hard-boiled detectives both have their origins in the pulp magazine tradition, so it’s not that far-fetched to combine them, as The Last Witch Hunter tries to do by casting Vin Diesel as an immortal medieval tough guy in a secret New York underworld of modern-day magicians. Muscling into magic-potion speakeasies and decrepit witch squats hidden behind gummy bear trees, Diesel’s trench-coat-clad Kaulder encounters hookah-smoking octogenarian femme fatales kept young and beautiful by sorcery and shape-shifters who resemble fidgety meth tweakers in their true form. When he isn’t using alchemy to dust crime scenes for spell fragments or getting knocked out by memory smoke (apparently the witching world’s equivalent of getting pistol-whipped on the back of the head), he beds stewardesses and fixes antique pocket watches in his Central Park pad.

The script is geek central, involving everything from Civil War trivia to role-playing game terminology, and has its share of dork cool (e.g., the witches’ legal system, in which jurists consult the tarot during the trial), so it’s a shame that The Last Witch Hunter ends up crumbling into another generic showdown of murky fantasy effects and snatched artifacts, with a final shot that is literally framed around a door to possible sequels. Perhaps part of the blame rests on the current business model of franchises, origin re-boots, and pre-planned trilogies, which has made the industry allergic to telling actual stories, as though leaving audiences satisfied might keep them from coming back in two or three years. Nowadays, effects-heavy fantasy flicks are generally made in halves or thirds, and The Last Witch Hunter is no exception.

Written by a brain trust of goofily over-serious dark fantasy franchise-launch veterans (Priest’s Cory Goodman, Dracula Untold’s Matt Sazama and Burk Sharpless), The Last Witch Hunter is set in a world where magic is real, but kept secret, protected by a centuries-long peace accord between occult and religious authorities. Kaulder—who slew a witch queen back in the Middle Ages, and was cursed to never die—works as the street muscle for a Catholic order, confiscating illegal weather runes and nabbing the occasional warlock crook, assisted by his secretary (Michael Caine), an elderly priest he addresses only as “Kid.” There’s a definite charm to this mashup of gumshoe mystery and fantasy, with Kaulder as the world-weary P.I. type who’s earned his cynicism by actually being the oldest man on Earth. (Diesel’s understated charisma, nightclub bouncer physique, and deep croak of a voice—all used to great effect in the genre-crossing Riddick movies—help a lot.)

If nothing else, The Last Witch Hunter deserves some points for trying to visualize a world where magic is something like a tumorous outgrowth of the natural world, eschewing dusty books and the usual indistinguishable globs of blue-green energy in favor of spells that erupt as swarms of butterflies or tangles of gnarled roots, cast with pieces of Iceland spar and 55-gallon drums of cemetery dirt. And though its dialogue is riddled with comically clunky exposition (sample exchange: “We took all the most powerful witches in the world and put them in one place.” “The witch prison!”), the movie has just enough offbeat details and just enough of a sense of humor to feel a little lived-in.

But then comes the intercut climax, in which our hero—who, up to that moment, has solved problems with a combination of wits, fists, and flirting—breaks out the flaming sword to defeat a generic cackling evil that is poised to wipe out the human race despite having all of two henchmen, and being not much more than a servant to future evils that will need defeating. The Last Witch Hunter is at its most appealing when its title character is just pounding the pavement and explaining clues out loud, and at its most unremarkable when it angles for something bigger: a series, which the movie—either naively or cynically—presents as the destiny Kaulder must accept. Say what you will about the Joseph Campbell-style hero’s journey, but at least it’s better than the hero’s contract extension.