Set in Washington, D.C., Election Year re-introduces the formerly nameless Leo (Grillo) working security for progressive presidential candidate Sen. Roan (Elizabeth Mitchell), whose platform includes eliminating the Purge, the free-for-all during which emergency services go dark and all crime is legal. Though the mechanics of the Purge remain mostly nonsensical, Election Year at least explains how anyone manages to stay in business in a country where everything goes to hell on an annual basis: a predatory, unregulated “Purge insurance” industry free to hike up rates just hours before the sirens sound the start of the killing. (Note: Though all crime is legal, the America of The Purge appears to be blissfully free of rape, arson, or plain old theft.) Unable to make his latest payment, middle-aged Joe (Mykelti Williamson) takes to the roof with a lawn chair and a rifle to protect his small convenience store, which is where Leo and Roan will eventually end up after surviving an assassination attempt.

Like Anarchy, Election Year works in the classic B-movie vein of ragtag groups moving under threat, with Joe, Leo, and Roan joined by Joe’s only employee, Marcos (Joseph Julian Soria), and by Laney (Betty Gabriel), a regular customer who’s part of a corps of volunteers who look for the wounded in D.C.’s less protected neighborhoods in armored “triage vans.” The first movie, a muddled home-invasion thriller set in a rich gated community, hinted that most of those killed in the Purge were black, but Election Year goes a few steps further, presenting the annual killing spree as a kind of end-game nightmare for black America, where anyone can get away with killing a black man and the economic and political system are rigged. (This is, sadly, not that far out.) Coinciding with the lead-up to the election, the Purges serve to violently curb voter turnout, and DeMonaco, never one for subtlety, also introduces the idea of “murder tourists” coming from abroad to participate—all white, hailing from places like South Africa and Russia. Just to drive the point home, David Bowie’s “I’m Afraid Of Americans” bellows over the end credits.

Instead of continually switching up threats, as Anarchy did, Election Year follows its characters as they evade a band of mercenaries—a sporadic tour through the ways alternate-future D.C.’s black residents survive, from secret underground hospitals to momentary alliances of street gangs, activists, and rescue volunteers. DeMonaco and cinematographer Jacques Jouffret, who have worked together on all three of the movies, have become more capable and confident when it comes to style. The first Purge could barely keep up a sense of tension; its slapdash camerawork made it impossible to figure out where anyone was at any given moment, despite the fact that almost the entire movie took place in a single house. Here, they’ve finally settled on a look, pulling the old low-budget trick of using a lack of lighting to effect.

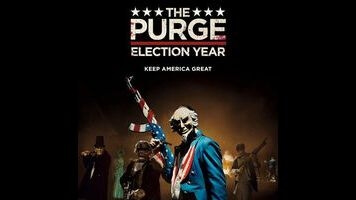

Unreadable shadows drop over character’s faces, while the aforementioned hospital appears to be lit entirely with practical sources (i.e. prop lamps, rather than big movie lights), contributing to an appropriately gritty vibe. And though DeMonaco’s dialogue skews laughably phony, it’s hard not to like the way he motivates his characters, setting up conflicts of goals rather than personalities. For all its flaws, Election Year has those baseline pleasures associated with violent American B-movies of the 1970s and ’80s—that mix of simplicity and scuzzy, juicy execution. One might accuse it of luridly chasing the politically topical, if only its images—even the really silly ones involving vampiric political lackeys and maniacs in bloody Abe Lincoln masks shouting “I love America!” in Russian accents—didn’t seem like they were coming straight from the gut.