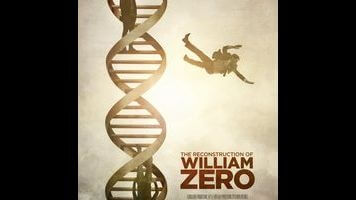

The Reconstruction Of William Zero is kind of a poor man’s Upstream Color

William Blakely thinks he’s a clone. Or at least he will soon enough. Initially, William (co-writer Conal Byrne) wakes up in a room with a man (also Byrne) who looks just like him. William has no idea why he’s there. His mind is a blank slate. He has to be taught the proper way to eat cereal and how to respond to a knock-knock joke. Perhaps the look-alike who’s instructing him is his twin brother? The scratchy home movies he’s being shown certainly suggest that. But who is that mysterious woman (Amy Seimetz) who’s always smiling into the lens?

Her name is Jules, and she’s William’s (the real William’s) wife. An early scene in Dan Bush’s unexceptional low-budget sci-fi feature reveals that William was once happily married with a son, but that all changed the day he carelessly backed out of the driveway and ran over the young boy. So the guilt-ridden William—a geneticist working at a research facility named Next Corp—channeled his grief into a new project: To literally create a better version of himself.

Saying any more would spoil the narrative twists Bush and Byrne have in store, though they’re dished out so inelegantly (via a lot of somnambulistic exposition) that they never truly surprise. It doesn’t help that Byrne makes for an extremely uncompelling protagonist(s). He looks like John Barrowman’s pudgier younger brother, and his acting style calls to mind the black hole that was the aptly named Stephen Lack in David Cronenberg’s Scanners. To say he’s not up to the task of playing two (and maybe three) separate characters is an understatement. His performance as the more mentally unhinged version of Blakely is particularly embarrassing—all smirks, bug eyes, and anal-retentive tics. (Nothing says evil quite like a slickly parted hairline.)

It’s a shame, because there’s a good movie lurking in here somewhere. The film’s primary inspiration appears to be the made-for-pennies mindfucks of Shane Carruth, not only in the hazily antiseptic visual style, but in the willfully cryptic narrative contortions and an emo-scientific climax that strains to touch both heart and mind. (Seimetz even seems to be riffing, to much lesser effect, on the anguished human lab rat she played in Carruth’s Upstream Color.) There’s a genuinely shocking murder sequence in a parking garage, one of the few times where the camera actually feels like it’s been positioned for maximum effect. And the places the story goes are at least moving and provocative in the abstract. It’s always easy to see what Bush and Byrne are aiming for with this timely piece of speculative fiction. But their execution is, with rare exception, weakly imitative at best and exasperatingly inept at worst.