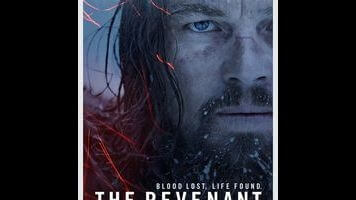

The Revenant's spectacular highs deserve a more focused vision

How many great scenes does it take to make a great movie? The Revenant has a few, scattered like acorns across two-and-a-half-hours.

How many great scenes does it take to make a great movie? The Revenant, a ravishingly violent Western survival yarn from Alejandro González Iñárritu, has a healthy few, scattered like acorns across its two-and-a-half-hour canvas. The first is a harrowing woodland skirmish, as Ree warriors ambush a hunting party from all sides. Arrows whizz into frame and flesh. Musket fire sends sniping archers tumbling from the treetops. It’s like the D-Day invasion of Saving Private Ryan but in reverse, with the beleaguered troops retreating to the water instead of charging onto land. And that’s arguably just an appetizer for the sequence that arrives a few minutes later, when one of the survivors of the massacre, famous frontiersman Hugh Glass (Leonardo DiCaprio), stumbles into the radius of a mama grizzly and her cubs. He’s mauled half to death for his troubles, the grueling battle with the bear unfolding through one of cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s signature single takes.

Getting brutalized by a grizzly is the real Hugh Glass’ claim to fame, though his standing in the history books probably rests more comfortably on what (according to legend) happened next: Living to tell the (tall?) tale, Glass traversed some 200 miles on a broken leg, all in pursuit of the companions who left him for dead. To dramatize this 1823 odyssey, Iñárritu dragged celebrated cast and crew to the rural reaches of Canada and Argentina; over budget and behind schedule, he braved inclement weather and shot only by natural light. The Revenant is his Fitzcarraldo, a film whose behind-the-scenes agony has become indistinguishable from that of the characters. And yet, as with the fractured, nonlinear ensemble dramas he used to make with screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga, there’s a sense that the whole doesn’t quite equal the sum of the parts, no matter how spectacular some of them are. (Even Birdman, the director’s newly minted Best Picture winner, operates best in the moment, the illusion of an unbroken shot notwithstanding.)

Working loosely from Michael Punke’s fictionalized novel, The Revenant embellishes some portions of the Glass mythology and chucks others entirely. (One curious omission: the hearsay that he staved off gangrene by letting insects feast on his rotten flesh, which sounds like exactly the sort of vivid anecdote you’d want to preserve.) The most significant liberty concerns the introduction of a fictional half-Pawnee son, Hawk (Forrest Goodluck), who’s there when his father is discovered in the South Dakota woods, a dead bear collapsed on top of him. Convinced that Glass won’t survive more than a couple days, the leader of his fur-trapping outfit, Captain Henry (a miscast Domhnall Gleeson), assigns two men—the young Jim Bridger (Will Poulter) and the duplicitous John Fitzgerald (a perfectly cast Tom Hardy)—to stay behind with Hawk and help him bury his old man after he dies. Greed and fear speed that timetable up, and soon Glass finds himself in a shallow grave, his son’s body nearby, Fitzgerald and Bridger fleeing the scene of the crime. The real Glass reportedly just wanted his stolen possessions back; this version is out for blood, and won’t let a few gashes and broken bones stand in his way.

And so The Revenant ends up uncomfortably perched between a kind of 19th-century Death Wish movie and a whispery Terrence Malick meditation on the relationship between man and nature. (There are heavy shades of The New World, provided not just by Lubezki, but also by fellow Malick mainstay Jack Fisk, the go-to production designer for ancient American encampments.) Part of the schizophrenia is inherent to the film’s conception of Glass, who comes across both as a mythic force of pure determination and a flesh-and-blood person nursing some serious wounds. His ageless baby face concealed behind a bushy Grizzly Adams beard, DiCaprio has been hired to endure endless Method-actor torments, to crawl screaming through the mud, to bloodily reenact the tauntaun scene from The Empire Strikes Back. What he hasn’t been hired to do is play much of a character; though The Revenant supplies Glass with plenty of wordless dreams, spiritual visions, and flashbacks to his dead loved ones, his family life remains as abstract as his psychology. He’s more macho concept than man.

Instead of immersing the audience in the six-week journey of this unstoppable folk hero, Iñárritu crosscuts among several different parties, leaving Glass’ side to periodically check in on: Captain Henry and his men, closing in on shelter; Fitzgerald and Bridger, bickering about the morality of what they did; a largely faceless group of French trappers; and the marauding Ree, who it’s eventually revealed are tracking a kidnapped daughter of the tribe, like the stars of an inverted The Searchers. (As with a lot of modern Westerns, The Revenant finds a middle ground between the racist, vilifying depictions of Native Americans in old Hollywood movies and the romanticized conception of them in films like Dances With Wolves.) Though the chronology remains linear, all this geographic leapfrogging recalls the structural strategy of Babel, wherein Iñárritu labored to draw connections between characters of different cultures. Here, it’s bloodshed and the unforgiving nature of the environment that links everyone; the filmmaker presents an unchained, dog-eat-dog America—at once filthy and stunningly beautiful, realistically rendered but populated by CGI animals—where everyone is always hunting and/or being hunted.

Does such a scattered focus represent a failure of nerve? The Revenant revels in striking imagery (a bell swaying in a hollowed-out church) and bursts of virtuosic violence (a climactic showdown of almost parodic extremity), but it can’t seem to commit to the meat of its “true” story—namely, that long, lonely, and arduous pilgrimage Glass took from the brink of death to what passed for civilization in his all-but-lawless age. On the other hand, given that the solitary, procedural passages of The Revenant are among its least distinctive, perhaps it’s for the best that Iñárritu didn’t try to go the full Werner Herzog (to name another primary influence). Besides, keeping the camera locked on DiCaprio would ultimately have deprived us of the film’s true standout performance: Tom Hardy as the weak-willed Fitzgerald. Mumbling in an accent that’s somewhere between Bane and Bronson on the intelligibility scale, Hardy is the most fascinatingly human character on screen—a rationalizing scoundrel whose selfish behavior lends him more dimension than the impossibly driven superman on his tail. Every time we’re sharing company with this flawed villain, crouched nervously over a fire or scheming in the foliage, the wait between jaw-dropping set pieces doesn’t seem so protracted.