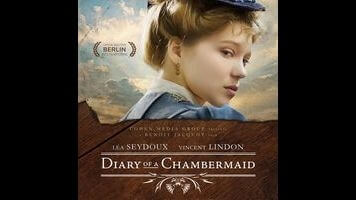

Suffering from a bad case of “too few and far between,” the new film adaptation of Octave Mirbeau’s turn-of-the-20th-century “succès de scandale” Diary Of A Chambermaid—which has already been made into movies by Luis Buñuel and Jean Renoir—does itself no favors by refusing to stick to a through-line. It touches on the novel’s pessimism, decadence, and politics only in brief, fervid moments. As in the other versions, chambermaid Célestine (Léa Seydoux, insouciant almost to the point of self-parody) arrives at the provincial Lanlaire household from Paris, becoming privy to local hypocrisies and delusions even as she develops a fascination with stable groom Joseph (Vincent Lindon), an apelike anti-Semite who plans to rob the Lanlaires and casually says things like, “Jews should be massacred; it’s the only solution.”

Buñuel’s version moved the time frame forward to the years before World War II, turning Célestine’s relationships with Joseph and the Lanlaires’ mean-spirited neighbor, a retired officer, into an allegory for a continent captivated by fascism. Renoir’s earlier take, made in Hollywood, located the James M. Cain-type noir melodrama in the story. The new Diary Of A Chambermaid—which takes just as many liberties as the previous adaptations—does a little bit of both, while also trying to work in erotic undercurrents and the novel’s original context in the time of the Dreyfus affair. In spurts, it resembles an homage to classic French cinema and an overheated, Tinto Brass-esque Euro skin flick, but still finds plenty of room for stultifying, upstairs-downstairs costume drama.

Is this a case of the source material being too perfect a match? Mirbeau’s novel fits right into the pet themes of prolific, hit-or-miss writer-director Benoît Jacquot—namely, women who defy easy psychologizing and the servant class (or “service industry,” in modern parlance) whose obligation to privacy and bodily functions (feeding, cleaning, etc.) ends up crossing over with sex and desire. Jacquot has literary bona fides, too, having started as an assistant to Marguerite Duras and tackled the likes of Yukio Mishima, Henry James, and Céline over the course of his career. (He just wrapped an adaptation of Don DeLillo’s The Body Artist.) But Diary Of A Chambermaid, which Jacquot co-scripted with Hélène Zimmer, lacks a unifying principle, as though the director were too eager to address subtexts to bother with text.

Jacquot’s eclecticism renders what would normally be buried themes into conspicuous features, as in his most recent film, the underappreciated 3 Hearts, which handled a rom-com-esque love triangle as though it were ominous suspense, creating palpable tension with unexpected camera movements and a thriller-grade score. He gets similar effects here, though only sporadically: a dolly-in on an ostrich feather here, an entire sequence of the porniest zooms imaginable there. Diary Of A Chambermaid comes together only when it frames the personal and professional relationships between Célestine, Joseph, and the Lanlaires (Clotilde Mollet and Hervé Pierre) in eerie erotic terms: an ivory dildo discovered in luggage; Célestine sneaking in to smell Joseph’s bed; an interaction with a brothel madam (Italian actress Adriana Asti) looking for fresh faces.

Jacquot has a knack for presenting the way drama and drudgery can intermingle in working life. (See: A Single Girl, still his best film, which follows a hotel employee in more or less real time.) His version of Diary Of A Chambermaid, however, never really invests its assorted intrigues with the same mix of prurience and genuine concern, even on a purely visual level; Jacquot seems more interested in the process of cleaning a chamber pot than in, say, whether Célestine thinks that Joseph had something to do with the 12-year-old girl found raped and disemboweled in the nearby woods.

The France of the 1880s—and, implicitly, the present—is crawling with lechers, lower-class stiffs who take comfort in being exploited, and chauvinists in both the classic French and modern American English sense. None of it seems to matter, least of all in Jacquot and Zimmer’s shrug of a revised ending. Nominally, Diary Of A Chambermaid is about the moral rot hiding below, but its most lasting impressions come from surface pleasures and barely motivated flourishes of style.