Spoiler Space offers thoughts on, and a place to discuss, the plot points we can’t disclose in our official reviews. Fair warning: Major plot points for Star Wars: The Rise Of Skywalker are revealed below.

It began even before the movie came out. In the press blitz surrounding

The Rise Of Skywalker, the stars and creators of the final film in the latest

Star Wars trilogy started tossing out weird statements that could only be read as veiled criticism of

The Last Jedi, the bold but divisive middle installment of the new series. John Boyega

expressed his discomfort with the core trio being separated for almost the entirety of the second film, though his dislike of that decision could be read as more an expression of simply missing his costars and wishing for the support of his two fellow leads on set during filming. (Also, has he seen

Empire Strikes Back? Luke is isolated as hell in that one.) Daisy Ridley

said she cried with relief at hearing Abrams was returning. And most telling of all,

J.J. Abrams said of Rian Johnson’s movie—and specifically, its decision to focus less on Abrams’ nostalgia-burdened mythology and more on, well, burying the past—“It’s a bit of a meta approach to the story. I don’t think that people go to

Star Wars to be told, ‘This doesn’t matter.’”

The language is a dead giveaway. What doesn’t matter? Not plotting, or characterization, or any of the things Johnson was clearly dedicated to, whether or not you agreed with his choices. No, what the guy who directed Star Trek Into Darkness seems to be saying is, “Why didn’t you make Rey’s parents the bloodline of someone we remember from the original trilogy? Why didn’t Luke immediately grab his lightsaber and start slicing up First Order stormtroopers? Why didn’t you deliver more fan service?” Someone should have told Abrams this was not going to go the way you think.

And so, with The Rise Of Skywalker, Abrams went ahead and did what a small but extremely vocal minority of Star Wars fandom wanted to do but couldn’t: He walked back the most compelling elements of The Last Jedi. And in so doing, he further weakens a franchise that already felt far too beholden to a demanding fanbase. J.J. Abrams (and Kathleen Kennedy, and the rest of Star Wars’ sort-of-creative team) goes further than the PR campaign to throw Rian Johnson’s movie under the bus; he negates the best things that movie did for this series—specifically, liberate it from the unimaginative need to be endlessly beholden to the past.

The conclusion of this trilogy jettisons much of the work done by Johnson’s film—to the point where, for all intents and purposes, The Rise Of Skywalker could almost pick up where The Force Awakens left off, were it not for a couple of characters pretty definitively dying in the interim. The most obvious of Abrams’ efforts to reverse The Last Jedi is the retconning of Rey’s parentage, making her the granddaughter of Emperor Palpatine. It’s a decision that doesn’t just undercut Johnson’s story, in which Kylo Ren reveals to Rey that her parents were nobodies, the better to reaffirm just how isolated and meaningless she is in the eyes of others. It also undermines the crux of Johnson’s point in making that narrative choice: that your past doesn’t define your future, and a hero who changes the course of the universe can come from anywhere.

By making her part of an aristocratic bloodline that directly ties her to the most powerful Sith Lord who ever lived (and died, and lived on as the undead, in this case), Abrams undercuts the entire emotional thrust of that story. Sure, he can include plenty of defensive speechifying from multiple characters about how we don’t have to let our ancestors define us, but it still upholds a mythos more dispiriting than any midichlorian—namely, that you can only really be special if you come from special beginnings. Multiple characters can be equally important parts of the story, but in true Animal Farm form, some are more equal than others. It’s like if someone revised Usain Bolt’s autobiography to say that his great-grandfather was Jesse Owens. “Oh, now he makes sense,” track-and-field fans could think. “Otherwise he’s just a Mary Sue!”

This need to continually return to the past, to tie everything back to something that came before rather than allow for an evolution into something new, is what kneecaps The Rise Of Skywalker, draining it of life and making it feel like a limp retread of Return Of The Jedi. (At least The Force Awakens was an energetic version of its antecedent, A New Hope.) Abrams’ kowtowing to noisy fanboys seems most blatant in the marginalization of Kelly Marie Tran’s Rose Tico, introduced as a major new character in The Last Jedi, yet now relegated to a barely-there role on the sidelines, à la Jar Jar Binks; it’s hard not to read it as a sop to the worst of the Star Wars audience. But the intent is clear even in Skywalker’s comic asides. When Rey returns to the same island on which Luke isolated himself for so long, determined not to let her vision of sitting on the evil throne come to pass, her deceased mentor returns, Obi-Wan-style, to counsel her. Saving the lightsaber Rey attempts to throw into the burning remains of her ship, he admonishes her, “A Jedi’s weapon deserves more respect!”

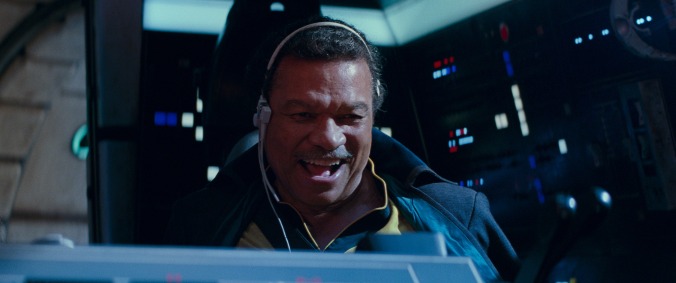

The most charitable reading of this line would be that it’s a little ironic joke, commenting on Luke’s own tossing aside of the same weapon as the inciting incident that begins The Last Jedi. But in this case, it’s also a dig at its predecessor, a repudiation of Johnson’s attempt to break free of the past and take the narrative in a new direction, offering these characters the possibility of doing more than simply looping through the same journey we’ve already seen. Abrams has no interest in breaking free; in his reading, Star Wars is supposed to deliver one thing, and you can find it in George Lucas’ original trilogy. So bring on Billy Dee Williams, and Tatooine, and even Harrison Ford himself, breaking his own vow of liberation from the past to strap on that damn belt one last time and let the memory of Han Solo guide Kylo back to being Ben. The past dictates all.

This undercutting of The Last Jedi defines The Rise Of Skywalker as definitively as the nostalgia it uses in place of a new narrative. Remember how surprising it was when Kylo smashed his helmet? Don’t worry, Abrams has him weld it back together. Startled when Snoke was killed by his acolyte? It’s fine, it was Palpatine working him like a puppet anyway, just as was intended, so that action didn’t really change anything. Were you as disheartened as Poe to learn his instincts were so wrong last time out? Fear not—in The Rise Of Skywalker, every good guy’s gut feeling is unerringly accurate, because this is a story terrified of challenging its audience in any way. The takeaway is a perverse inversion of the old saying, Those who forget the past are missing out on a primo opportunity to repeat it.

There’s still plenty to enjoy in Abrams’ film, especially the performances. Ridley, Boyega, and Isaac once more all do strong work, elevating even the most forced moments of character. And Adam Driver finally gets to inject some levity into his perpetually angry Kylo Ren: There’s the great moment where he leaps down into the pits of Exogol, landing hard on a rock outcropping only to mutter a terse, “Ow.” Or when he and Rey perform their lightsaber hand-off trick, and Kylo reveals his weapon to his former Knights with whom he’s about to do battle, giving a slight whaddya-gonna-do shrug and the barest hint of a smile. And Abrams still has an aptitude for crafting larger-than-life spectacle: The action may often feel rushed and perfunctory, but certain shots (the collapsing Star Destroyer, Rey slicing Kylo’s ship apart) are as striking as anything in The Force Awakens.

Still, how discouraging to see a movie so anxious to please all people—even (or especially) the ones who loudly conveyed their dislike of the previous film—that it walks back everything interesting and ambitious about its predecessor. What makes it all the more unfortunate is that these creative choices (or lack thereof, really) won’t do anything to please people who consider The Last Jedi a betrayal. Much like their ossified nostalgia, that movie isn’t going to retroactively change. The Rise Of Skywalker can’t undo the past; it can only unimaginatively pretend it doesn’t exist. And if anyone should know the danger of hiding from what has come before, it’s those continuing the Skywalker legacy.