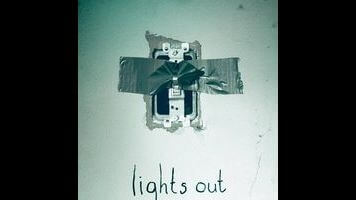

It’s a pity, because Lights Out would function perfectly well if it were just about that most primal, even universal of phobias: a fear of the dark. Starkly, efficiently conveyed by the one-sheet, the premise gets its first workout during the suspenseful opening scene, wherein some poor schmuck, working late at his creepy mannequin factory, succumbs to a malevolent force darting across the shadows. Surviving daughter Rebecca (Teresa Palmer) leaves home soon after, moving in above a tattoo parlor, plastering her walls in Avenged Sevenfold posters, and never letting nice-guy beau Bret (Alexander DiPersia) sleep over. What she’s really running from is her mother, Sophie (Maria Bello), who exhibits the usual symptoms of untreated depression, plus an unusual one: long conversations with a croaking silhouette in their underlit suburban home. This unnerving entity was a staple of Rebecca’s childhood, and now it’s returned to scare the shit out of her little brother, Martin (Gabriel Bateman).

Disappearing when the lights are flipped on and lurching forward with a herky-jerky J-horror stagger when they’re off, “Diana” is a reasonably spooky creation, even if her metaphoric function is baldly clear from the onset. The film goes overboard explaining her origins, unpacking boxes of pertinent backstory and at one point literally scrawling some expository information on the wall. But making Mom the one with the “imaginary” friend is a clever reversal of a very hoary horror trope, and director David F. Sandberg otherwise finds inventive ways to exploit his gimmick. The cold open, for example, makes cruelly nerve-wracking use of an overhead light on a motion-detection timer, while a later scene creates strategic blackouts from the rhythmic, blood-red pulse of the tattoo parlor’s neon sign. Burning through every source of illumination imaginable, the movie almost plays like the horror-flick version of Kanye’s “All Of The Lights”: Streetlights! Headlights! Black lights! Wind-up flashlights!

The simplest but possibly most effective of the film’s tricks—Diana blinking in and out with the nervous working of a light switch, before suddenly teleporting across the room—is straight from the source material, a miniature master class in terror from 2013. Two and a half minutes may have been the ideal length, frankly. Because in expanding Sandberg’s short into a first feature, produced by Conjuring mastermind James Wan, Lights Out gains the whole ghost-as-mental-disorder angle—and that’s where this stylish but lunkheaded fright flick goes very, very wrong. Sandberg conceives of Sophie only as a sullen mess of tics—a despondent mother whose one and only character trait is her despondency. (Bello, wasted in the role, lets the heavy bags under her eyes do the heavy lifting.) This is a movie about depression that treats the afflicted like little more than gigantic burdens on their families, right through to an ending that carries the toxic implication of that attitude to its logical conclusion. If you’re going to lend your B horror film a stealth social-issues dimension, you have to be aware of what stance on that issue you’re intentionally or unintentionally taking. Lights Out is one case where they should have let the monster just be a monster.

For thoughts on, and a place to discuss, plot details we can’t reveal in this review, visit Lights Out’s Spoiler Space.