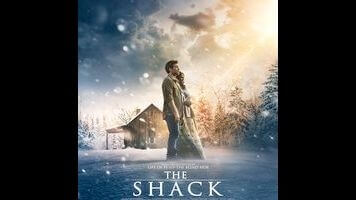

The Shack dares to ask, “What if God were a character actor?”

Sam Worthington should’ve been a criminal. The man could rob a bank in broad daylight on payday and the police still wouldn’t be able to draw a composite sketch. That’s not a knock against his acting—he’s better than he’s given credit for being, and so is Jai Courtney. But as for his face, his features, his bearing—they just don’t seem to stick. All one can say is that he definitely looks like an actor from film or TV, somewhat beefier than a regular man. Obviously Australian, too, because he’s no good at accents. In The Shack, he plays a native of the rural Midwest, but speaks in a throaty, Eastwood-ian accent that goes for a walk any time he has to whisper or feel something. The Shack is dumbfounding, by the way—an adaptation of an “inspirational” novel (with three authors, so you know it’s good) about a man who spends a weekend hanging out with God after his daughter is murdered by a serial killer who preys on children at campgrounds. “Hanging out with God” is not a figure of speech. The Shack is one of those things that sounds bug-nuts but is really just a chore to sit through.

There’s a canoeing accident and “an old Indian legend” involved—and other stuff that we’ll get to in time. But the whole film is a crime against narrative, so bungled that it might actually be the victim of sabotage. Like the serial killer subplot: It’s such tasteless overkill, as though the loss of a child under ordinary circumstances were not tragic enough, but it also requires a belabored setup that unfolds in a very long flashback, triggered when Worthington’s character, Mackenzie “Mack” Phillips, slips on some ice in his driveway and hits his head. It’s random enough that the film almost leaves room for the possibility that Mack himself murdered his daughter. He offs his abusive father in the first five minutes by pouring a lethal dose of strychnine into some whiskey, but that’s a different matter. This act of patricide is supposedly not a part of the novel that The Shack is based on, and has almost no bearing on the movie. It’s addressed so vaguely that it’s debatable whether it’s addressed at all.

What’s important is that before hitting his head on the driveway, Mack finds a note that he understands to be from God, and it tells him to go to the scene of his daughter’s murder, which he does after stealing a truck from buddy Willie (country star Tim McGraw). And there he finds the Almighty living in a woodland cottage, like something out of a Thomas Kinkade print. God asks to be addressed as “Papa” but takes the form of Mack’s pie-baking childhood neighbor (Octavia Spencer) with the logic that the man has enough daddy issues that it’s probably best for him not to think of his creator as male for the time being. Mack also meets Jesus Christ (Avraham Aviv Alush), who looks pretty much as expected, and the Holy Spirit (Sumire Matsubara), who seems to have taken some really great drugs. Later on, Papa decides that Mack needs a more fatherly presence and transforms into the Canadian character actor Graham Greene. He is credited as “Male Papa,” which is a great set of words.

Mack isn’t much of a protagonist—sort of an all-purpose jeans-wearing, hardworking family man, though what he does for a living is never mentioned. He has a wife (Radha Mitchell) and two surviving children, a son (Gage Munroe) and a moody teenage daughter (Megan Charpentier), and they all live somewhere in the Pacific Northwest. Worthington brings exactly as much to a role as he’s given, which isn’t a whole lot in this case. The director, Stuart Hazeldine, is a Brit who’s had some success as a script doctor, though you wouldn’t know it by The Shack. There’s nothing about this unconscionably long movie (it runs a whopping 132 minutes) that suggests anyone involved ever watched it from start to finish. But it looks nice enough, like a Nicholas Sparks adaptation, with lots of flowers and flannel.

Most of its running time is taken with mollifying conversations between Mack and the movie’s New Age-meets-Bible Belt oversimplifications of the Holy Trinity. It fits right into a long tradition of quasi-mystical pseudo-parables. Pick your poison: The Celestine Prophecy, The Five People You Meet In Heaven, Jonathan Livingston Seagull, The Teachings Of Don Juan. This one, though, has a ladybug-themed serial killer in it, as well as what appears to be an homage to Aaron Katz’s mumblecore anti-mystery Cold Weather. Though as with the will of God, one can’t fully grasp the intention. Destin Daniel Cretton, who made Short Term 12, and John Fusco, the writer of the Brat Pack Western Young Guns and the creator of Netflix’s Marco Polo, both worked on the screenplay, and who knows what either of them thought they were doing.

It’s easy to put together a subversive reading of the film as a depiction of the delusions of a guilty conscience. There’s fuel for that, like the fact that the serial killer’s face is never shown and that, when Papa asks Mack to forgive him, she mentions their similar childhoods. There’s a lot more where that came from. Plus, just to be clear, Mack does get away with murder in the opening sequence (which, like much of the movie, is for some reason narrated by his friend Willie), and this murder is never exactly mentioned. He even meets his father’s ghost later on, and it’s the ghost that begs him for forgiveness, which is just screwed-up. Then again, this is also a movie where the protagonist climbs inside of a mountain to meet a personification of divine wisdom and has a footrace with Jesus across a lake, with both scenes handled as literally and passionlessly as possible. It doesn’t take any imagination to picture God’s forgiveness as a nice lady who’ll talk you through your problems or a wise older man who will lead you up a hiking trail. It’s the silent cosmic unknown that’s actually difficult. A lot less boring, too.